The Inquiry Report

This document may not be fully accessible.

Acknowledgements

The conclusion of my Report could not have been achieved without the diligence of Angela Worth as Secretary to the Inquiry, who assumed the responsibilities of that role following the departure of Ann Martin. Angela managed the preparation for and the administration of the public hearings efficiently, enabling me to ensure that they commenced on time and concluded within the allotted nine months. Thereafter the core members of the Secretariat, consisting of the Secretary to the Inquiry supported by Ann Peffers and Nenko Nedialkov, provided me with invaluable administrative support and gave a commitment to remain as members of the ETI team until the conclusion of the Inquiry following the transfer of its records to the National Records of Scotland. I am extremely grateful to them for their diligence and helpful advice throughout.

I also acknowledge the invaluable assistance provided by the three Counsel to the Inquiry led by Jonathan Lake QC (now Lord Lake KC). Apart from preparing for and conducting the public hearings Mr Lake gave me sound advice on significant issues that arose at different stages of the Inquiry. In the litigation in the Court of Session at the instance of Bilfinger Construction UK Limited (Bilfinger) Mr Lake, assisted by Mr McClelland, Advocate, successfully resisted the challenge to my decision to refuse a restriction order relating to documents produced by Bilfinger to the Inquiry.

The acknowledgement of the legal support that I received would not be complete without recognising the significant contribution of Gordon McNicoll, the Solicitor to the Inquiry. His unexpected retirement for health reasons was a serious loss to the Inquiry’s legal team but thankfully he was able to return as Solicitor to the Inquiry when the post became vacant as a result of the transfer of Timothy Glennie to the Legal Department of the States of Jersey.

Guide to Reading the Report

Where the Report can be found

The Inquiry Report is published on the Edinburgh Tram Inquiry website at: https://www.edinburghtraminquiry.org/

as fully searchable web (HTML) text and downloadable PDF file.

To access either version of the Report, click the “The Inquiry Report” tab on the “Home” page on the Inquiry website.

Structure of the Report

The Report comprises 25 chapters, 8 appendices, 24 recommendations and an Executive Summary.

At a very early stage of the Inquiry, it was considered impracticable to set out the events in chronological order because of the need to examine particular matters as distinct issues in some detail. A particular issue may arise in different contexts and is addressed in each chapter in the context of the subject-matter of that chapter. The heading of each chapter identifies its subject-matter. It will be apparent that this approach may result in a certain amount of repetition, but that has been minimised by the use of cross-references, although in some instances it was considered necessary to have a certain amount of repetition.

Apart from the recommendations relating to Public Inquiries generally, which are contained in Chapter 2 concerning the establishment and progress of the Inquiry, it was not feasible to include recommendations within particular chapters. This is because the basis for many of these recommendations is contained in several chapters. Accordingly, recommendations 5–24 inclusive are contained in Chapter 25, after the findings in fact, and they should be read in the context of the Report as a whole. For ease of reference, a list of all of the recommendations has been prepared and appears immediately before the Executive Summary.

Documents and Referencing

Documents referred to in the Report have been published on the Inquiry website and are identified by a reference code consisting of a three-letter prefix followed by eight numbers. The three-letter prefix is derived by the source of the document, as shown in the table in the Glossary. Document references appear in bold in brackets (for example, [CEC00775849]) and contain a hyperlink to the document as published on the Inquiry website. Alternatively, click on the document search box at the top right on each chapter page. This re-directs the reader to the “Find Documents” search function on the Documents page on the Inquiry website. Where reference was made to several parts of a multi-part document – for example, [CEC00775849, Parts 3-7] – the document code (CEC00775849) is hyperlinked to the first part in the reference (in this case, Part 3). To view other parts of a document, please use the document search functionality on the Inquiry website as described above, and search for the document code (in this case, CEC00775849). This will return all document parts.

Where reference is made to a document, using the document referencing system mentioned above, the standard referencing “[ibid]” has been used in all subsequent references to that document, until reference is made to another document. The word “[ibid]” contains the hyperlink to the original document.

Where a quotation from a document contains a spelling, grammatical or other error, but has been reproduced as originally written, “[sic]” has been used to indicate that the error appears in the original document.

Page numbering was automatically inserted in documents by the Inquiry’s document management system, Relativity, on the bottom right of each page. On pages with landscape orientation, page numbering may appear in the left page margin. Page numbering uses the format CEC00775849_0053, i.e. document code_page number, and may not follow from page numbering used by the document creator/owner. For multi-part documents the original page numbering remains continuous throughout all document parts.

Where footnotes have been used, these are clearly notated with a number in superscript, which contains a hyperlink to the footnote’s text at the bottom of the page. Clicking on the in-text reference number will direct the reader to the relevant footnote text at the bottom of the page. To go back to the in-text reference, readers should either click on the return arrow icon at the end of the footnote, or use the “go back” button in their Internet browser.

Glossary

Below is a list of acronyms used in the Report. Each acronym is expanded on first use in a chapter unless it appears in quoted text, in which case in order to preserve the integrity of the source document the meaning has not been added to the acronym. An acronym may have two meanings that refer to its use in the original documents: for example, “QC” may mean “Quality Control” and also “Queen’s Counsel”.

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

|---|---|

| the Act | Inquiries Act 2005 |

| the 1991 Act | New Roads and Street Works Act 1991 |

| AFC | approved for construction |

| ALEO | arm’s-length external organisation |

| AMIS | Alfred McAlpine Infrastructure Services Limited |

| BB | Bilfinger Berger UK Limited/Bilfinger Berger Civil UK Limited/Bilfinger Construction UK Limited, all referred to as Bilfinger Berger or BB |

| BBS | Bilfinger Berger UK Limited and Siemens plc, known as Bilfinger Berger Siemens or Bilfinger Siemens Consortium |

| BCR | Benefit to Cost Ratio |

| BDDI | Base Date Design Information |

| BSC | Bilfinger Berger, Siemens and Construcciones y Auxiliar de Ferrocarriles SA Consortium |

| BT | British Telecom |

| CAF | Construcciones y Auxiliar de Ferrocarriles SA |

| Carlisle 1 | first Project Carlisle proposal |

| Carlisle 2 | second Project Carlisle proposal |

| Carillion | Carillion Utility Services Limited |

| CEC | City of Edinburgh Council |

| CEO | Chief Executive Officer |

| CERT | Central Edinburgh Rapid Transport |

| CIPFA | Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy |

| COSLA | Convention of Scottish Local Authorities |

| CPO | Corporate Programme Office |

| D&W | Dundas & Wilson |

| Deloitte | Deloitte & Touche Limited |

| DfT | Department for Transport |

| DLA | DLA Scotland LLP, DLA Piper Rudnick Gray Carey Scotland LLP and DLA Piper Scotland LLP being the name changes of the firm of solicitors representing tie |

| DPD | Design, Procurement and Delivery |

| DPOFA | Development Partnering and Operating Franchise Agreement |

| DRP | dispute resolution procedure |

| EARL | Edinburgh Airport Rail Link |

| ENTICO | A company used as a vehicle for the incorporation of tie |

| ETN | Edinburgh Tram Network |

| FBC | Final Business Case |

| FBCv1 | First version of the Final Business Case |

| FBCv2 | Second version of the Final Business Case |

| GPR | ground-penetrating radar |

| GRBV | Governance, Risk and Best Value Committee |

| IFC | Issued for Construction |

| Infraco | Company/consortium that carried out the construction and engineering work on the tram line. Initially the consortium comprised Bilfinger Berger, Siemens (BBS), but it included CAF following novation, although BBS carried out the work. |

| Infraco contract | Infrastructure contract |

| INTC | Infraco Notice of tie Change |

| IOBC | Interim Outline Business Case |

| IPG | Internal Planning Group |

| ISIS | Information Services and Information Systems Division |

| IT | information technology |

| ITN | invitation to negotiate |

| JRC | Joint Revenue Commission |

| LB | Lothian Buses |

| McNicholas | McNicholas Construction Services Limited |

| MFRA | Moray Feu Residents’ Association |

| Minister for Transport | Minister for Enterprise, Transport and Lifelong Learning |

| MoU | Memorandum of Understanding |

| MoV | Minute of Variation |

| MoV4 | Minute of Variation 4 |

| MoV5 | Minute of Variation 5 |

| MUDFA | Multi-Utilities Diversion Framework Agreement |

| NAO | National Audit Office |

| NIA | Notice of Intention to Award the Infraco contract and/or Tramco contract |

| NTI | New Transport Initiative |

| OB | optimism bias |

| OGC | Office of Government Commerce |

| OJEU | Official Journal of the European Union |

| OLE | overhead line equipment |

| OSSA | On-Street Supplemental Agreement |

| PA1 | Pricing Assumption 1 |

| PB | Parsons Brinckerhoff |

| PFI | Private Finance Initiative |

| PMP | Project Management Panel |

| PPP | public–private partnership |

| the project | Edinburgh Tram project |

| PRINCE2 | PRojects IN Controlled Environments |

| PSSA | Princes Street Supplemental Agreement |

| QA/QC | quality assurance/quality control |

| QRA | quantitative risk analysis |

| RTN | Remediable Termination Notice |

| SAK | Stirling–Alloa–Kincardine railway |

| SDS | System Design Services |

| SDS Contract | System Design Services Contract |

| SG | Scottish Government |

| SGLD | Scottish Government Legal Directorate |

| SGN | Scotland Gas Networks |

| SNP | Scottish National Party |

| SMT | Senior Management Team |

| SP4 | Schedule Part 4 to the Infraco contract |

| SRO | Senior Responsible Owner |

| SRU | Scottish Rugby Union |

| STAG | Scottish Transport Appraisal Guidance |

| TAG | Transport Analysis Guidance |

| TEE | Transport Economic Efficiency |

| TEL | Transport Edinburgh Limited |

| tie | tie Limited (formerly Transport Initiatives Edinburgh Limited and now CEC Recovery Limited) |

| TMO | Tram Monitoring Officer |

| TPB | Tram Project Board |

| TPD | Tram Project Director |

| Tramco | Company tendering for, and ultimately awarded, the contract for the supply and maintenance of the tram vehicles |

| Tramco contract | Tram vehicle supply and maintenance contract |

| Transdev | Transdev Edinburgh Tram Limited |

| TROs | Traffic Regulation Orders |

| TSS | Technical Support Services |

| VE | value engineering |

Document codes used in the Report and provider organisations

| Document Cipher | Document Provider/Type |

|---|---|

| ADS | Audit Scotland |

| BFB | Bilfinger Construction UK Limited |

| CAR | Carillion Utility Services Limited |

| CEC | City of Edinburgh Council |

| CZS | Responses to the Call for Evidence |

| DLA | DLA Piper Scotland LLP |

| GOV | Scottish Government |

| PBH | Parsons Brinckerhoff |

| PHT | Public Hearing transcript |

| SCP | Scottish Parliament |

| SIE | Siemens plc |

| SWT | Sweett Group |

| TIE | tie |

| TRI | Written witness statements (including closing submissions) |

| TRS | Transport Scotland |

| USB | Interim Document Management (initial material provided to the Inquiry in summer 2014) |

| WED | witness evidence |

List of Figures and Tables

Figures

Figure 1.1 Planned construction phases of lines 1 and 2

Figure 1.2 Tram route for phase 1a

Figure 20.1 Project governance structure as agreed by CEC on 25 August and 2 September 2011

Figure 20.2 Project governance structure as at 27 March 2013

Figure 22.1 Project organisation: the integrated project team

Figure 22.2 Governance structure during construction period

Figure 22.3 Tram organisational structure

Figure 22.4 Proposed governance structure for Integrated Edinburgh Transport Authority

Tables

Table 6.1 Periods during which most significant critical issues affecting SDS contract remained unresolved

Table 8.1 Sections of the route of line 1a

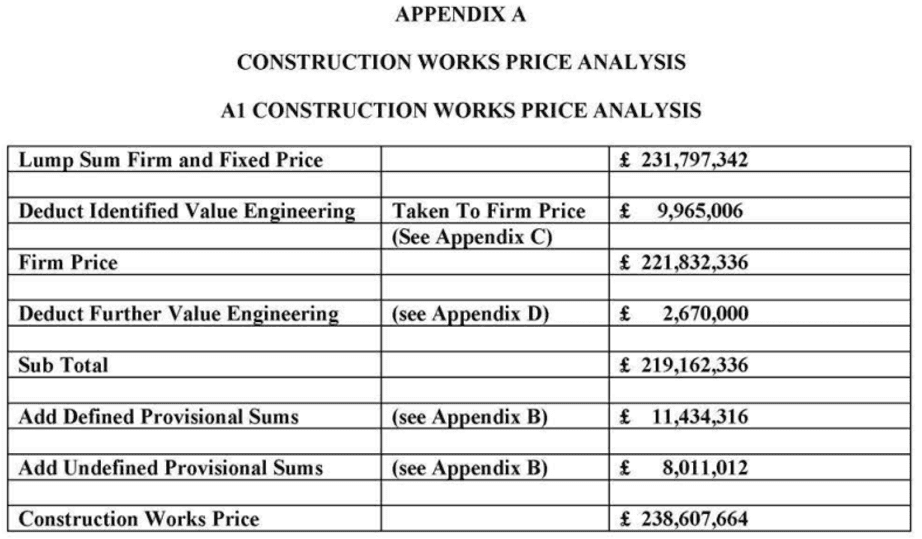

Table 9.1 Construction Works Price Analysis

Table 10.1 Attendance at joint meeting of tie Board and TPB on 15 October 2007

Table 19.1 Estimates of cost of change in construction works (on-street sections)

Table 19.2 Estimates of cost of change in construction works (off-street sections)

Table 19.3 Additional duration of sub-contractors’ programme

Table 19.4 Cost of options to be considered by CEC on 30 June 2011

Table 19.5 Estimated cost of options excluding risk allowance

Table 20.1 Comparison between Financial Close Budget and Estimated Final Expenditure

Table 21.1 Proposed modification to risk allowance in February 2008

Table 21.2 Proposed modification to risk allowance at Financial Close

Table 22.1 Membership of TEL Board and Tram Project Board

Table 24.1 Estimated cost to public purse

Table 24.2 Updated TEE Outputs (Source – JRC, June 2011)

Table 25.1 Construction Works Price Analysis

Recommendations

1. Scottish Ministers should undertake a review of public inquiries to determine the most cost-effective method of avoiding delay in the establishment of an inquiry, including consideration of establishing a dedicated unit within the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service and publishing regularly updated guidance for people involved in the establishment and progress of public inquiries.

2. In any event Scottish Ministers should not appoint as the sponsor of any public inquiry any department, agency or other government organisation where it, or any of its employees, has had any involvement in the project or other event giving rise to the establishment of the public inquiry.

3. The guidance mentioned in the first recommendation should include: advice concerning the circumstances in which civil servants in the inquiry team may properly transfer to posts, other than promoted posts, within other government departments or agencies; which positions within the administration of a public inquiry may be filled by the employment of agency staff; and whether longer-term contracts as temporary civil servants are more appropriate for particular positions that cannot be filled by permanent civil servants.

4. In reporting the cost of a public inquiry Scottish Ministers should report its net cost to the public purse, after discounting expenditure already incurred on accommodation, staff and other resources, as well as the total cost appearing in the accounts of the sponsor department.

5. Where the Business Case for any future light rail project is based upon an assumption that, prior to the award of the contract for the construction of the infrastructure, certain matters will have been completed (eg design, the obtaining of all necessary approvals and consents or the diversion of utilities), the contract negotiations should be delayed until completion of these matters has been achieved, failing which before any infrastructure contract is signed a new Business Case should be prepared on the basis of the altered assumptions that prevail and should be approved by the promoter and owner of the project.

6. All versions of the Business Case, including any Business Case required as a result of altered assumptions, should include an assessment of risk that takes account of optimism bias in accordance with published government guidance.

7. The assessment of risk at each stage mentioned in Recommendation 6 should be the subject of a peer review by external consultants with experience of similar large-scale infrastructure projects in the transportation sector, who should submit a report of each review to the promoter and owner of the project as well as to the procurement and project manager sufficiently far in advance of the signature of the infrastructure contract to enable the promoter and owner to consider whether to authorise its signature and, as appropriate, to consider any other available options requiring a strategic decision.

8. The existing Guidance on optimism bias was based on empirical data available almost two decades ago and should be revised to take into account the additional data that is now available. In particular, the reference classes should be updated to include a specific reference to light rail projects and the recommended uplifts for the different reference classes should be adjusted to reflect the additional empirical data that is now available. Thereafter the Guidance should be reviewed and revised to take account of additional data on a regular basis at intervals of not more than five years.

9. The identification and management of risk should be an integral part of the governance of all major public-sector contracts in future. In identifying and managing risk the following principles should be adopted.

- Probabilistic forecasts rather than single-point forecasts should be used to take account of the risk appetite of funders and project sponsors.

- Funders, sponsors and project managers should be cautious when adjusting uplifts and there should be critical review of claims that mitigation measures have reduced project risk.

- Effective governance needs to provide constant challenge and control of the project, including recording of where the project is compared with its baseline, and reacting quickly to get the project back on track, whenever there are signs that it is veering off course. This necessitates providing senior decision makers with data-driven reports on project performance and forecasts combined with reports by the management team and independent audits.

- In reporting to governance bodies there should be special emphasis on detecting early warning signs that the cost, schedule and benefit risks may be materialising so that damage to the project can be prevented. If early warning signs do emerge, the project should revisit assumptions and reassess risk and optimism bias forecasts.

- The quality of evidence rather than process is the key to providing effective oversight and validation.

10. In the interests of protecting the public purse and maximising the benefits from public expenditure on major projects, the Scottish Ministers should contemplate establishing a joint working group consisting of officials in Transport Scotland and representatives of the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (“COSLA”) to consider how best to take advantage of:

- tolerating the risk of cost overrun that is always a possibility in risk assessments by including all public-sector light rail projects in the portfolio of large projects undertaken by the Scottish Ministers, including those to be constructed wholly within the geographical boundaries of a single local authority;

- the greater experience within Transport Scotland of managing major projects in the public sector; and

- the necessary skills and expertise within Transport Scotland to deliver the project on time and within budget.

11. The Scottish Ministers and local authorities responsible for funding light rail projects should be mindful at all times of their obligation to protect public funds and to obtain value for public expenditure. In that regard:

- the Scottish Ministers should impose conditions on the payments of grants, similar to the “hold points” imposed on the offer of grant made on 19 March 2007, that enable them to review at each “hold point” whether the scheme is continuing to meet its objectives and to determine whether to continue to support the funding and implementation of the scheme;

- continued financial support from the Scottish Ministers should require their critical review of all versions of the draft Business Case and their approval of the final Business Case as well as their review, and approval before signature, of the draft contracts for the delivery of the project;

- the Scottish Ministers should be involved in the delivery of the project as they were before the withdrawal of the support of officials from Transport Scotland in 2007 and following the resumption of infrastructure works after the mediation settlement at Mar Hall; and

- as a condition of the grant the local authority should be obliged to comply with the project monitoring and control procedures of Transport Scotland and should ensure that robust, transparent, externally verifiable project controls for the project are in place.

12. For reasons of transparency and accountability for public expenditure the Scottish Ministers should keep minutes of:

- the nature and content of any discussions and the reasons for any decisions taken at all meetings, discussions or telephone conversations, and in email or other correspondence between a Minister and civil servants relating to the nature and extent of any involvement by civil servants in the procurement and delivery of a project funded or to be funded in whole or in part from public funds (including a grant from the Scottish Ministers);

- all discussions between a Minister and representatives of a local authority, the company responsible for the procurement and delivery of a publicly funded project or the company responsible for its construction to record what was discussed and what, if any, decisions were reached and the reasons for any such decision; and

- all discussions between a Minister and civil servants including telephone discussions concerning any negotiations, including, but not restricted to, negotiations at mediation for settling disputes involving contracts funded or to be funded in whole or in part from public funds (including a grant from the Scottish Ministers) to record what was discussed and what, if any, decisions were reached and the reasons for any such decision.

13. The procurement strategy for any future light rail project should make adequate provision for the uncertainties concerning the location of utilities and redundant equipment belonging to present and past utility companies, particularly in urban centres. In particular, although it is not possible to be prescriptive about the appropriate timescale:

- the procurement strategy should include a requirement that the route of the track should be exposed and cleared of utilities well in advance of the infrastructure contractors commencing their work;

- the procurement strategy should specify the period that should elapse between the exposure and clearance of the route and the commencement of construction, to ensure that the contractors have unrestricted access to the construction site and may proceed with the infrastructure works unencumbered by the presence of utilities;

- in fixing the period mentioned above, the procurement strategy should take into account the length of the route to be constructed, past experience of the time taken for the diversion of utilities in light rail projects in other parts of the UK, and any additional constraints peculiar to the project such as an embargo on work to divert utilities during particular periods such as the festive season or special events (e.g. the Edinburgh Festival).

14. Although some participants in the Inquiry criticised the use of the Multi-Utilities Diversion Framework Agreement (“MUDFA”) to divert utilities in advance of the infrastructure works and advocated the “bow wave” approach to the diversion of utilities that followed the mediation settlement at Mar Hall, I do not think it appropriate to be prescriptive about how the risks associated with the diversion of utilities are managed. It is sufficient for promoters of light rail schemes to be aware of such risks and to demonstrate that they have adequate proposals for managing them.

15. In recognition of the various difficulties likely to be experienced in the design and construction of a light rail project through a city centre, the promoter and owner of the project should appoint as its procurement and project manager a company with suitably qualified and experienced permanent employees that has delivered a similar project successfully on time and within budget or can demonstrate that it will be able to do so.

16. Immediately following the appointment of the designer and throughout the design of the project the designer should engage with the promoter and owner of the project, the procurement and project manager, the local planning authority, the utility companies and interested third parties owning land that may be affected by the project, to clarify their design criteria. In such discussions throughout the design of the project the promoter and owner of the project should co-ordinate responses to the various stages of design and, in doing so, should take into account the competing interests of different parties and of various departments within any local authority exercising different statutory functions as well as the significance of the project in the context of the community as a whole and should provide all necessary assistance and clear and timeous instructions to the designer to avoid delays and additional expense. In that regard:

- prior to the appointment of the designer the local planning authority ought to produce sufficiently detailed design guidelines to enable the designer to take them into account from the outset when designing the tram network, and to improve the prospects of obtaining the necessary consents and approvals without requiring repeated re-submission of designs that will result in delay to the project with resultant expense;

- throughout the project a collaborative approach should be adopted by the promoter and owner to achieve an early resolution of any design issues that arise; and

- the promoter and owner should assume primary responsibility for co-ordinating the local authority’s response and for negotiating the resolution of all issues, to enable clear instructions to be issued to the designer and to avoid re-design of sections of the route following reconsideration of matters that have been resolved at an earlier stage.

17. The governance structure for the delivery of a major project such as a light rail scheme should follow the published guidance and should ensure that there is clarity regarding the respective roles of the various bodies and individuals involved in its delivery. In particular, the chairman of the company responsible for the procurement and management of the project should not also be its chief executive.

18. As part of their investigations representatives of OGC undertaking an independent “readiness review” of a publicly funded project and representatives of any person, including representatives of any public body such as Audit Scotland, undertaking a review of the progress of and/or expenditure on a project funded in whole or in part by public funds should be required to interview key personnel involved in the project to ensure that each of them understands his or her role and is performing it effectively. In preparing any list of key personnel to be interviewed the individuals undertaking the investigations shall include the person designated as SRO.

19. At all stages of the project there should be a collaborative approach to delivering it. This should include the co-location of representatives from each organisation relevant to the particular stage reached and having an interest in its completion to enable any issues to be addressed and resolved at the earliest opportunity, thereby minimising the risk of the escalation of disputes with associated delays and increased expense.

20. The directors, employees and consultants of the company responsible for the procurement and delivery of the project as project managers, including an arm’s-length external organisation (“ALEO”) wholly owned by the local authority that is the promoter and owner of the project, should not submit to the local authority information that is deceptive or reports that are misleading either by the inclusion of false statements or by the omission of references to facts that might influence the strategic decisions of councillors if they were disclosed. In that regard they should recognise and respect the need for local authority officials to scrutinise and challenge the accuracy of information and reports submitted to them and should not seek to frustrate, or interfere with, the instruction of independent consultants to advise officials on the accuracy of the risk assessment in such reports or on the terms of any draft contracts for which they seek authority to sign.

21. Local authority officials should be mindful at all times of the distinction in roles between them and councillors, who are solely responsible for strategic decisions, and of their duty to provide accurate reports to councillors to enable them to take informed decisions based upon the reality of the situation. Such reports should not be misleading either by the inclusion of false statements or by the omission of relevant facts. Where officials prepare and submit reports based upon reports to them from an ALEO acting as the procurement and delivery vehicle, they should not assume the accuracy of these reports based upon the adoption of a “one family” approach involving the local authority and the ALEO.

22. Where a company, including an ALEO, knowingly submits a report or other information to local authority officials that is misleading by reason of the inclusion of false statements or the omission of relevant facts or where such officials knowingly submit misleading information to councillors, whether or not councillors act upon that information, the Scottish Ministers should consider whether there should be an appropriate sanction in damages against the relevant individuals within the company responsible for the false statements or omission of relevant facts, as well as against the company itself, and against the relevant local authority officials involved in submitting misleading information to councillors.

23. In addition to any civil liability arising from any sanction introduced in accordance with Recommendation 22, the Scottish Ministers should consider whether there is a need for a statutory criminal offence involving strict liability once it is established that the information and/or report was misleading by reason of the inclusion of false statements or the omission of relevant facts.

24. The Scottish Ministers should also give consideration to the need for legislation to impose a similar duty of disclosure to that owed by policyholders to their insurers upon a company, its directors, employees or consultants and upon a local authority and its officials towards representatives of OGC or of Audit Scotland undertaking any review of a publicly funded project. Any such legislation should determine the appropriate civil and/or criminal sanctions to be imposed for breach of the duty of disclosure.

Executive Summary

Background

1. The construction of the Edinburgh Tram Network (“ETN”) was identified as a proposal in the City of Edinburgh Council’s (“CEC’s”) New Transport Initiative (“NTI”), a long-term project involving a number of transportation proposals to be funded by road user charging, also known as congestion charging. On 19 October 2000, CEC approved a draft Local Transport Strategy which identified a number of proposals including the development of a tram network. CEC concluded that there was a need to incorporate an arm’s-length external organisation (“ALEO”) to operate the proposed congestion charging scheme and to use the revenue from it to fund the transportation projects identified by CEC.

2. Apart from being able to recruit staff with the necessary skills to operate such a scheme without the constraints of public sector pay scales, an ALEO could use the revenue stream from congestion charging to borrow funds in the open market without being hindered by borrowing constraints imposed on local authorities by the Scottish Ministers or the United Kingdom Government. Accordingly, in 2002 CEC incorporated “Transport Initiatives Edinburgh Limited”, which was wholly owned by CEC, and which later changed its name to “TIE Limited” and is now known as “CEC Recovery Limited”. Throughout this report, “tie” is used to refer to that company whatever its name at the relevant time.

3. Following its incorporation tie produced a report entitled “A Vision for Edinburgh” [CEC01623145], which set out a programme for the development and implementation of £1.5 billion-worth of transport improvements, using public and private sources of funding including congestion charging. The programme required the early support of the Scottish Ministers

“principally through agreement to provide £375 million of funding towards the development and construction of three tram lines, which form a key part of the improved transport infrastructure” [ibid, page 0004].

4. The Scottish Ministers guaranteed the availability of that sum of money to ensure that funding for at least the first tram line was available as soon as CEC produced a robust Final Business Case (“FBC”); see Chapter 5 (Procurement Strategy). The funding was not conditional on the introduction of congestion charging. After the abandonment of congestion charging in 2005 CEC retained ETN as a major construction project although no reassessment of the project’s viability appeared to be undertaken at that time.

5. The Tram project was the largest capital project undertaken by CEC in living memory. It remained politically controversial throughout the lifetime of the project. CEC had a budget of £545 million for the project, consisting of a grant of £500 million from Scottish Ministers (being the original sum of £375 million mentioned above with indexation applied to it) with the balance being funded by CEC. The budget included the purchase of tram vehicles to operate on the network as well as the construction of the network itself.

6. Although CEC was the promoter of the necessary private legislation consisting of two separate Bills authorising the construction of lines 1 and 2, it used tie to represent its interests in the proceedings before the Scottish Parliament. tie was also responsible for the preparation of the Business Case for the Tram project and for the procurement and delivery of the project. tie determined the procurement strategy and concluded the various contracts necessary for the delivery of the project with CEC acting as guarantor of tie’s financial obligations, as a result of which all financial risk of exceeding the available budget of £545 million remained with CEC.

7. Price certainty was important for CEC. Councillors’ support for the project and their authorisation to tie to enter into the necessary contracts for the project was given on the basis that phase 1a (from the Airport to Newhaven) at least was to be constructed and opened for service in the summer of 2011 within the budget of £545 million, with an expectation that part of phase 1b (from Roseburn to Granton) might also be constructed within that budget.[1]

8. In May 2008, in the exercise of delegated powers granted by the councillors, CEC’s then Chief Executive (Mr Aitchison) authorised tie to sign the necessary contracts for the construction of phase 1a of the network and the manufacture, delivery and maintenance of the tram vehicles. The contracts were signed on 13 and 14 May 2008.

9. Although the procurement strategy had envisaged that tie would conclude a separate contract for the purchase and maintenance of the tram vehicles which would be novated to the infrastructure consortium (“Infraco”) upon signature of the infrastructure contract (“Infraco contract”), in the Rutland Square Agreement dated 7 February 2008 tie agreed to Construcciones y Auxiliar de Ferrocarriles SA (“CAF”), the supplier of the tram vehicles, joining the consortium with Siemens plc and Bilfinger Berger (UK) Limited (“BBS”) either before or following the signature of the Infraco contract and the novation of the tram vehicle supply and maintenance contract (“Tramco contract”). Following the signature of the Infraco contract on 14 May 2008, which included the Tramco contract as a separate schedule, the consortium included CAF and became known as BSC. Despite the obligations of BSC to deliver the project, it should be acknowledged that the difficulties with the implementation of the strategy related to the infrastructure works to be undertaken by BBS.

10. After a delay of almost three years, line 1a of the ETN was opened for revenue service on 31 May 2014, although its extent was restricted to a line from the Airport to York Place (the “restricted line 1a”) rather than to Newhaven as had been the intention in the FBC. The restricted line 1a was reportedly completed within an increased budget of £776 million. In light of the reported increased cost of £231 million and of the restricted scope of the network that was delivered, as well as the delay in opening the truncated line for service, Scottish Ministers commissioned this Inquiry.

11. Before considering the reasons for the failure to deliver the entirety of line 1a on time and within the budget of £545 million it may be helpful to consider the actual cost of the restricted line as well as the estimated cost of the extension to Newhaven to enable a comparison to be made between the anticipated final total cost of line 1a and the original budget of £545 million. It is also convenient at this stage to consider the consequences of the additional cost incurred in constructing the restricted line 1a and of the delay in its construction.

Actual cost of the restricted line to York Place

12. There is uncertainty about the final total cost of completing the restricted line 1a. Following the settlement reached at the mediation at Mar Hall in March 2011, work on the construction of the restricted line 1a recommenced and the projected budget for completing it was £776 million. In March 2017, CEC reported the cost of completing

the restricted line 1a as £776.7 million, being £231.7 million in excess of the budget of £545 million (the “additional expenditure”). Most of the additional expenditure within the reported cost of £776.7 million related to the total cost of the works by BBS under the Infraco contract. It was £427,206,309.52 for the restricted line 1a, compared with the original construction works price of £238,607,664.00 for a line between the Airport and Newhaven (the “entire line 1a”).

13. The reported cost of £776.7 million was not, however, an accurate statement of the total cost because it underestimated outstanding claims by third parties, principally because CEC was unaware of a substantial claim that had not been intimated at that time; it did not include certain costs such as the cost of other infrastructure works undertaken by CEC directly attributable to the Tram project but allocated to other CEC budgets; it failed to include a pension fund deficit arising from the cessation of tie’s business; it omitted compensation payments to businesses and the Net Present Value of the cost of borrowing the additional £246.5 million needed to complete the project. Taking these items into account, the best estimate of the total cost of the restricted line 1a is £835.739 million.

14. Had the increased budgeted cost of the restricted line (£776 million) been known before CEC approved the FBC on 20 December 2007, the Benefit to Cost Ratio (“BCR”) would have been 0.73, indicating that neither CEC nor the Scottish Ministers would receive value for the anticipated public expenditure. In that situation CEC could not have justified proceeding with the project and the Scottish Ministers could not have justified payment of the grant of £500 million towards its funding and would have needed to consider their available options, including the possibility of constructing a shorter line within the available budget assuming that its economic appraisal produced a BCR greater than 1.

Cost of line 1a from the Airport to Newhaven

15. The full cost of the entire line 1a, and the extent to which it has exceeded the budget of £545 million, will only be known once the extension from York Place to Newhaven has been completed and its cost added to the £835.739 million estimated cost of the restricted line 1a. Based upon the estimated cost of £207.3 million, including risk, support for business, and optimism bias, in the business case submitted to CEC in 2019 in support of the extension from York Place to Newhaven, the total expenditure on line 1a will exceed £1,043 million – almost double the original estimated cost. That difference will obviously increase if the estimated cost for the extension is exceeded. In reporting the cost of the extension from York Place to Newhaven, officials should include all tram-related expenditure and recharge any such expenditure that may have been allocated to other CEC budgets, as occurred with the restricted line, as well as including the net present value of any borrowing by CEC to fund the extension.

Consequences of increased costs and delay

16. The most obvious consequence of the increased costs was the effect upon CEC’s finances. CEC had to borrow £246.5 million to complete the restricted line 1a. Increased borrowing results in the commitment of additional future revenue expenditure to enable sums borrowed to be repaid with interest. A consequence of that commitment is the lost opportunity for CEC represented by its inability to provide the level of service to the community throughout the 30 year repayment period of the loan that it would otherwise have been able to fund from its revenue account without such a commitment. The annual revenue charge of £14.3 million required to repay capital and interest of the sum borrowed to complete the tram line to York Place represented 1 per cent of CEC’s gross expenditure and is an indication of the money that would otherwise have been available annually over a period of 30 years to fund services in the City of Edinburgh. Moreover, if there has been any additional borrowing to fund the extension the loss of money available to fund such services annually over the period of repayment will be increased. More significantly it will result in an increase in the loss of CEC’s opportunity to fund future services because of the need to repay capital and interest arising from the additional borrowing.

17. I accept that the effect on funding for future services is a consequence of borrowing by local authorities to fund capital projects. However, it seems to me that different considerations apply where borrowing for a capital project is planned in advance of the local authority’s commitment to proceed with that project and the cost of borrowing is included in the business case for the project. In that situation councillors will be aware of the implications for future services of borrowing funds to deliver the project. In this instance councillors were concerned to have price certainty and they authorised construction of the ETN based on assurances by their officials, who in turn relied on assurances by tie, that the line from the Airport to Newhaven could be constructed and the necessary vehicles purchased within the available budget of £545 million. Councillors did not anticipate, and were not advised to anticipate, any restriction on the future provision of Council services if they authorised officials to proceed with the project based on the FBC. No provision was made for the borrowing of £246.5 million or for any additional sum to complete the extension from York Place to Newhaven. Such borrowing was unplanned at the outset, and its costs are a direct consequence of the failure to deliver line 1a within the available budget.

18. A further financial consequence for CEC of the failure to complete the line to Newhaven on time was the loss of fare box revenue from passengers who would have used the tram service if the line had been completed as planned. That loss has been estimated at £4 million per annum. It also resulted in the loss of the anticipated benefit of a tram service as a catalyst for the development and regeneration of the Leith and Newhaven areas. In that regard it failed to deliver the benefits anticipated in the FBC.

19. Apart from the consequences for CEC another obvious consequence of the delay in the completion of line 1a as originally planned was the effect upon businesses and residents along the proposed route, as well as upon residents in streets used for diverted traffic and upon the public whose access to the city was impeded and whose travelling time to work increased.

20. Although I acknowledge that the calculation of losses suffered by businesses that are directly attributable to the construction work is complicated by the effects of the recession following the banking crisis in 2008, the evidence has persuaded me that the delay in the construction work and the associated disruption were significant contributors to the losses incurred by businesses at that time. Businesses along the route of line 1a, particularly in the west end of the city and in the section between York Place and Newhaven, suffered loss because of the disruption caused by the construction works, which impeded access to their premises by prospective customers and goods delivery personnel. Some businesses ceased trading altogether, and others reported significant losses. While some disruption during the construction phase was inevitable, the disruption to businesses in these localities lasted much longer than would have occurred if the project had been completed on time. The disruption to businesses in the section between York Place and Newhaven, particularly on Leith Walk and in Constitution Street, will have continued during the construction of the extension of the line to Newhaven. This additional disruption would have been avoided if line 1a of the project had been completed on time and without restriction of its scope.

21. Residents along the route of line 1a also experienced loss of amenity due to noise and disturbance as well as considerable inconvenience for much longer than anticipated because of difficulties of access to their homes caused by the construction works and during prolonged periods when barriers impeding access to their homes remained in place when no work was being undertaken. Residents in other residential streets were adversely affected by diverted traffic, including heavy goods vehicles, for several years longer than should have been the case because of the failure to complete the project on time. The public, especially those with more restricted mobility, had difficulty in accessing the city centre because of barriers erected to enable construction to be undertaken but which remained in place when work had ceased pending resolution of disputes. Traffic diversions adversely affected residents throughout the city and commuters to it.

Causes of failure to deliver project within budget and to the extent projected

22. The principal causes of the failure to deliver the project within budget and to the extent provided can be summarised as follows.

- tie’s departure from the procurement strategy that had been intended to manage risk out of the project.

- The failure of tie to work collaboratively with CEC and others including, in particular, Parsons Brinckerhoff (“PB”) and BSC.

- Failure by tie to report accurately on progress and failure by CEC officials to monitor progress.

- Delay with production of design due to poor performance by PB and failure by tie and BSC to manage the design contract effectively.

- tie’s failure to follow the guidance about optimism bias when preparing various versions of the Business Case such that the cost of the project was underestimated.

- tie’s failure to achieve the price certainty sought by CEC and to transfer risk to BSC in accordance with the procurement strategy.

- The negotiation of the Infraco contract on terms that were inconsistent with the FBC and prevented progress being made in the construction of the project when there were Notified Departures from the pricing assumptions in the contract.

- The governance structure did not follow any recognised model. There was a lack of clarity as to who had responsibility for the performance of certain tasks and there was some overlap regarding the respective roles of the various bodies created, and individuals appointed, to deliver the project. It is also unclear whether all of the individuals appointed to specific roles actually fulfilled these roles.

- The failure of CEC’s officials to protect CEC’s interests as the client and promoter of the project bearing the risk of exceeding the allocated budget of £545 million.

- The Scottish Ministers’ decision following the debate in Parliament on 27 June 2007 to withdraw the involvement in the project of officials in Transport Scotland resulting in a loss of expertise in the management of major transport infrastructure projects and in particular a lost opportunity to review the FBC and the draft Infraco contract before its signature.

These will be considered in the sections that follow.

Procurement strategy

23. As I have noted in paragraph 4 above, the grant from the Scottish Ministers depended upon CEC producing a robust FBC. tie had the responsibility of preparing the FBC but it had to be approved by CEC. In that regard CEC wished the price certainty necessary to ensure delivery of the project within the available budget of £545 million.

24. Between 2002 and 2004, tie ran a procurement group that was tasked with considering how best to procure the tram system. The procurement group included professional advisers from various disciplines, including DLA Piper Scotland LLP (“DLA”), Grant Thornton, Mott MacDonald, Faber Maunsell, and Partnerships UK. A report by the National Audit Office (the “NAO”) published in 2004, which was entitled ‘Improving public transport in England through light rail’ [CEC01708649], noted the poor financial performance of several existing light rail schemes, and the tendency of scheme promoters to seek to transfer as many of the project risks as possible to the private sector. Such factors were leading to inflated project costs, because the private sector either avoided light rail projects altogether (removing competition) or sought greater margins for taking the risks. The NAO suggested that better sharing of project risk and alternative contract structures could help to reduce the cost of such projects and encourage private sector investment.

25. Following the above advice from the NAO, tie developed a procurement strategy that involved having separate contracts with different contractors for distinct parts of the project. In accordance with that strategy the contracts for the construction of the network infrastructure and for the purchase and maintenance of the tram vehicles were to be negotiated separately. tie negotiated the contract for the construction of the network infrastructure with BBS and the contract for the purchase and maintenance of the tram vehicles with CAF respectively.

26. By contracting separately for the purchase and maintenance of the vehicles (under the Tramco contract) tie would not be restricted to a supplier that was part of the consortium selected to deliver the project. The greater choice of vehicle suppliers ensured that tie secured a competitive price and avoided the infrastructure contractor adding any risk premium or other surcharge in respect of the vehicle supply and maintenance contract. No issues of delay or increased cost of the Tram project arose in respect of the Tramco contract, apart from the additional storage costs incurred by CAF associated with the delay in tie taking delivery of the vehicles as a consequence of the delay in progressing the project.

27. Bearing in mind CEC’s desire for price certainty and the report from the NAO, tie’s procurement strategy was intended to take active steps to manage risk out of the project. Apart from the separation of the procurement of the Tramco contract and the Infraco contract mentioned in paragraph 25 above, these included: prior to the conclusion of the Infraco contract, providing Infraco with completed designs with all necessary approvals and consents subject to the population of these designs with specific systems and components chosen by Infraco; novating the design contract to Infraco at the date of signature of the Infraco contract; and completing the diversion of utilities in advance of the infrastructure work to enable Infraco to construct the tram line unimpeded by the existence of utilities.

Failures in implementing the strategy

28. Although some witnesses from tie criticised the procurement strategy, I have concluded that it was a sensible response to the difficulties experienced elsewhere in the UK in the construction of light rail systems. The difficulties with the project were not attributable to the procurement strategy; they were a result of tie’s failure to implement it in relation to the completion of design in advance of the Infraco contract and the diversion of utilities in advance of the infrastructure works. It seemed to me that criticisms of the strategy by tie witnesses were motivated by a desire to divert attention from their own failures.

Design

29. The procurement strategy was intended to limit the allowance for risk related to design that would be included by Infraco in the Infraco contract price. The method for achieving this was that, prior to the award of the Infraco contract, tie would conclude a contract for System Design Services (the “SDS contract”) with a provider of such services (the “SDS” provider), who would develop the design to a certain level and obtain all necessary consents and technical approvals from CEC and from third parties such as Network Rail, Forth Ports Authority, Edinburgh Airport and Royal Bank of Scotland who might be affected by the design of the route.

30. The effect of this strategy was that tie would bear the risk of design prior to the signature of the Infraco contract, thereby avoiding the inclusion in the contract price of a risk premium for design that contractors would normally add to their bid if they had the responsibility for designing the project and for obtaining the necessary approvals and consents. Upon signature of the Infraco contract the SDS contract would be novated to Infraco, who would thereafter accept design risk and would complete the design by incorporating the components and systems upon which its bid had been based and would carry out the construction, installation, commissioning, and maintenance planning in respect of the ETN. If that strategy had been implemented, tie would not have incurred any additional expense resulting from any design change after the Infraco contract was signed unless tie had requested such change and, in terms of the change provisions in the Infraco contract, had agreed the cost of such change in advance of instructing Infraco to proceed with it.

31. tie signed the SDS contract with PB on 19 September 2005, but tie lacked the necessary skills to manage that contract to ensure that design was completed as planned before the signature of the Infraco contract. Initially, tie appears to have thought that it could simply rely on the obligation on the SDS provider to produce design and obtain approvals in accordance with the design programme, with minimal involvement by tie in the design process. Moreover, tie and PB failed to engage CEC in the design process at the outset and to ascertain the wishes of CEC which was responsible for granting planning and technical approvals as planning and roads authority. tie also failed, in conjunction with CEC, to ascertain at the outset and thereafter manage the expectations of third parties whose consent was required for the design of sections of the route affecting their property.

32. The strategy relating to completion of design was intended to provide potential infrastructure contractors with an informed basis for pricing their bids, thereby reducing the need for risk premiums and increasing the probability of achieving the price certainty that CEC sought. However, completion of the design was delayed. At the date of signature of the Infraco contract, design was incomplete and subsequent development of the design, treated by the contract as change, was inevitable. Concluding the Infraco contract while the design was incomplete was a material departure from the procurement strategy and failed to transfer risk to Infraco to the extent upon which the FBC was based, meaning that the desire for certainty as to price could not be achieved. tie ought to have delayed signature of the Infraco contract and the novation of design until the design was nearer completion but it refused to do so, reflecting a marked reluctance within tie to do anything that would delay the award of the Infraco contract. Although there was a recognition within tie that the price for the Infraco works was not fixed at contract close, contrary to the procurement strategy, elected members of CEC were not made aware of this development. Although some CEC officials were aware that the price for the Infraco works was not fixed at contract close most CEC officials were not, due to the fact that they relied on what was reported to them by tie and its advisers. There was a failure by CEC officials to take separate advice to protect CEC’s interests.

33. The primary responsibility for the delay in completing design lay with tie for mismanaging the design contract. tie acted for CEC during the Scottish Parliament’s consideration of the private legislation promoted by CEC to enable the construction of the ETN. In the summer and autumn of 2005 the Scottish Parliament was considering various proposed amendments to the alignment of the route and did not conclude its consideration of that issue until Christmas 2005. Nevertheless, tie concluded the SDS contract three months prior to the conclusion of the parliamentary procedure.

34. Moreover, significant changes were made to the original plans and sections submitted to the Scottish Parliament, particularly those for Haymarket Yards, Newhaven, and the Gyle. At Haymarket Yards, the route changed completely. The changes also included changes to the horizontal and vertical limits of deviation. PB had not been involved in the parliamentary process and tie failed to notify it of these changes with the result that the preliminary design was prepared from the wrong baseline. The changes to the baseline from which PB had to prepare designs and the failure of tie to keep PB informed of such changes meant that PB had to carry forward elements of preliminary design into the detailed design phase. This prevented the orderly progression of design and introduced the risk of tie, or CEC, requiring changes to the preliminary design during the detailed design phase. tie’s failure to inform PB of the changes when they arose reflects upon its poor management of the project.

35. Underlying tie’s mismanagement of the design contract was its unrealistic programme for design delivery. The draft FBC [CEC01821403] prepared by tie and presented for approval to councillors on 21 December 2006 included a programme summary, showing that detailed design for phase 1a was due to be completed and all approvals and consents to be obtained by 4 September 2007, with the Infraco contract being awarded in October 2007. The programme had little float and was based upon the assumption of “right first time and on-time delivery of activities” [ibid, page 0164, paragraph 11.3]. tie’s aspirations for the completion of design within that timescale were unachievable. In its comments dated 30 March 2007 on the draft FBC [TRS00004145, page 0009] Transport Scotland queried whether the intention to complete design by October 2007 was realistic. Mr Harries and Mr Glazebrook, two of the most experienced consultants at tie, did not think that the design would ever be delivered to programme when they were involved in the project. Mr Harries was involved in the project between November 2004 and February 2008 and Mr Glazebrook commenced work with the project early in 2007 and remained until 2011.

36. The programme was never achieved, and tie’s solution to design delay, following Mr Gallagher’s mantra of getting design “right first time and on time delivery”, was unrealistic and displayed a lack of appreciation of the iterative nature of design and of the challenges in obtaining planning and technical approvals in a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The delay in completing design in accordance with the programme was compounded by tie’s failure to provide PB with instructions on critical issues, resulting in PB ceasing work on the SDS contract between February and June 2007. By the summer of 2007 it was apparent to tie’s senior management that it would be impossible to complete the design in accordance with the programme.

37. Further examples of tie’s mismanagement of the design contract include the following.

- tie failed to respond to the preliminary design within the period of 20 days specified in the SDS contract, resulting in PB proceeding to detailed design in the absence of tie’s responses to the preliminary design because of the limited time allowed for design. This had an adverse effect upon the orderly progression of design.

- tie failed to engage with CEC and third parties at an early stage in the design process to determine their wishes and requirements and to manage their expectations. The result was frequent and belated requests for changes to design including the reconsideration of options that had already been rejected.

- Different teams within tie requested that PB prioritise different items of design, at different times, in a manner that lacked co-ordination, resulting in an inefficient process to produce design.

- tie’s procurement team amended the Employer’s Requirements to take account of its discussions with Infraco bidders without reference to PB and PB continued to develop the design based on the original Employer’s Requirements. In early 2007, it became evident that the proposals received from the Infraco bidders, the Employer’s Requirements and the SDS design did not align.

38. In May 2008, tie agreed to settle various claims by PB for additional costs, arising largely because of the delays in progressing design, including change notices issued from October 2006 onwards. The additional payments totalled £7,452,343 and represented an increase more than 30 per cent above the SDS contract price. The amount of the additional payments indicates the extent of the changes and delays that occurred in the design process before the award of the Infraco contract. The fact that tie agreed to make these additional payments to PB suggests that it recognised that many of the changes and delays to design before the award of the Infraco contract had occurred for reasons for which tie was responsible.

39. Although tie’s mismanagement of the design contract was the primary cause of the delays in design, CEC’s failure to clarify its requirements and the requirements of interested third parties before the commencement of design also contributed to delays in the design of the project. As owner and promoter of the project and as the statutory body responsible for granting planning consents and technical approvals for the project, CEC failed to provide adequate guidance about the design principles to be applied. Although, around December 2005, CEC did produce a Tram Design Manual [CEC00069887], which gave some guidance on design principles, that guidance was of a very general nature, and it was not until April 2008, a month before the Infraco contract was signed, that CEC produced a draft Tram Public Realm Design Workbook, [PBH00018590; CEC02086917; CEC02086918; CEC02086920–CEC02086934][2] which was intended to supplement the guidance in the Tram Design Manual [CEC00069887] and the Edinburgh Standards for Streets [CEC00669586] and to assist PB in developing the details of the designs for the City Centre to obtain consents and approvals. Such guidance was produced too late. CEC ought to have produced sufficient detailed design guidelines before the SDS contract between tie and PB was signed to enable PB to take them into account when designing the tram network. Had that occurred it is likely that PB would have received the necessary consents and approvals from CEC sooner than occurred and there would have been more likelihood of implementing the procurement strategy in relation to design.

40. For the sake of completeness, I acknowledge that PB recognised its failures in the production of the design of the project, principally by omitting to engage with CEC prior to the commencement of the SDS contract to discuss CEC’s design requirements and, prior to the arrival in 2007 of Mr Reynolds, by failing to manage change control effectively. However, these failures do not alter my conclusion that tie and CEC were principally responsible for design delay. Any criticisms of PB require to be viewed in the context of the environment in which it was working, being one of continual changes, a failure to close out issues and poor overall project management by tie.

Novation of the design contract to Infraco

41. Novation is a process whereby, with the agreement of all parties, all rights and obligations under a contract are transferred from one party to another. Commonly, the agreement for novation will state that the relationship between the provider of goods and services and the “new” client will be regulated by – and be taken always to have been regulated by – the existing contract and that, as between the existing parties to the contract, that contract shall be regarded as at an end. This means that the parties to the original contract no longer have rights against, or obligations owed to, each other and the new party stands in the shoes of the party that has been released from its obligations. It is up to the parties to determine how their relationship(s) should be structured, and it may differ from what I have just described, but in the Tram project it followed that outline. This meant that not only would the contractual relations concerning design in the period following novation be between PB and BSC; it would be as if this had always been the case. The only rights and obligations that tie would have in relation to design would be against BSC.

42. In terms of the SDS contract tie was entitled, but not obliged, to require that contract to be novated to Infraco when the Infraco contract was signed. Although the concept of novation of the design contract was predicated upon the assumption that design would have been completed to the extent specified in the SDS contract and that PB would have obtained all necessary approvals and consents before the signature of the Infraco contract, tie insisted upon novation of the SDS contract to Infraco despite the incomplete design and the absence of a substantial number of approvals and consents. That was a serious error by tie. The incomplete design and the fact that not all the necessary consents and approvals had been obtained had to be reflected in the terms of the Infraco contract. The result was that the risk of design development was not passed to Infraco as intended and tie retained a significant risk of design change after the award of the Infraco contract, with consequential increases in the cost of the project.

43. By insisting upon the novation agreement when design was incomplete, tie transferred control of completion of the design process to BSC but retained the significant risk of increased cost associated with it. In his oral evidence to the Inquiry Mr Maclean, Head of Legal and Administrative Services at CEC from December 2009, observed that the novation of the design contract in such circumstances meant that the designer and the contractor were “on the same team” [PHT00000008, page 42].

44. The novation agreement also amended the SDS contract by removing the absolute obligation imposed upon PB to obtain all necessary consents and approvals. Instead, PB would not have to bear the costs of amendments required by any approval body where the requirements were:

- inconsistent with or in addition to the Infraco proposals or the Employer’s Requirements;

- not reasonable given the nature of the approval body; or

- not foreseeable within the context of the Infraco proposals or the Employer’s Requirements.

In any of these circumstances tie bore the financial risk related to obtaining consents and approvals.

45. After novation, slippage in the design programme and delays in the obtaining of consents and approvals continued. The continual slippage in design is apparent from the fact that Version 51 of the SDS programme was provided to BSC on 23 November 2009 [recorded in PB progress report for January 2010, BFB00004338, page 0005, paragraph 2.3], whereas in May 2008, when the Novation Agreement was signed, version 31 was current [Close Report, CEC01338853, page 0007, paragraph 2.2]. The dispute between tie and BSC as to where responsibility lay for completion of design was a principal cause of the slippage of design because PB was unwilling to alter the design without being assured of payment from BSC. Moreover, internal reports by BB referred to the late production of design by Siemens that PB required to complete its design. Both of these were indicative of the failure of BSC to manage the design at least until it signed an agreement with PB on 25 February 2010 [TRI00000011] resulting in PB committing more resources to design and BSC guaranteeing payment in full for some of PB’s services and 75 per cent of the costs of others. In relation to the latter group, BSC would seek the whole amount from tie and PB would assist them in this. If BSC were successful in recovering all the cost from tie, it would make a balancing payment to PB so that PB would also be paid in full for these services.

46. Design remained incomplete in March 2011 during the mediation at Mar Hall. Although BSC bears some responsibility for failing to manage the design contract post novation and for the delay in reaching the agreement with PB on 25 February 2010 to enable progress to be made with design, the principal cause of design delay after novation was attributable to the dispute that arose between tie and BSC as to which party was to bear the risks under the Infraco contract arising from the development and completion of design and the concerns about whether PB would be paid for work that was the subject of that dispute. The responsibility for that situation rests with tie and, in particular, the persons responsible for negotiation of the terms of Schedule Part 4 to the Infraco contract (“SP4”) that are considered below in the context of the negotiation of the Infraco contract on terms that were inconsistent with the FBC.

47. The extent of the problem with design after novation is reflected in the payment of £14,117,112 made by BSC to PB in relation to services provided between SDS novation in May 2008 and the completion of the project. Although that payment included sums relating to additional services not included in the SDS contract, the payments made in respect of design core scope and design change, for design completion and for prolongation, exceeded £9.3 million, representing a further increase of approximately 40 per cent of the SDS contract price of £23,329,853.

48. I consider that CEC bears some responsibility in this period just as it did before contract close. CEC continued to fail to work in a collaborative manner to resolve design issues swiftly and with clarity or to provide a focus on enabling the project to proceed smoothly. The lateness and sheer volume of its comments were bound to cause delay and expense. I accept that as a public body with statutory responsibilities it would be inappropriate or even unlawful for it to fetter its discretion. The change that came about after the Mar Hall mediation, however, is striking. There is no suggestion that CEC ignored or in any way compromised its obligations in that period, and yet matters were dealt with in a wholly different way. The number of CEC staff allocated to the design process increased significantly and they were co-located with representatives from BSC and PB. The impression that I have is that, prior to the agreement at mediation, each department or section of CEC had been focusing only on what the ideal position would be for its own particular responsibilities. In effect, CEC commented with a number of voices rather than a single considered voice. The decisions made by local authorities in relation to consents etc. are usually matters that require some judgement, which involves balancing different – and sometimes competing – issues before reaching a single concluded view; they are not black and white. As such, it would have been legitimate to consider (when commenting on design) the overriding CEC view that there should be a tram system and that it would bring benefit to the city. Had there been someone with responsibility to oversee and co-ordinate the response from CEC to the many requests for approvals and consents, I think it likely that the responses would have been more proportionate, focused and reasonable. Without this, in carrying out its work, PB in effect had to meet the requirements of multiple departments with divergent interests.

Utilities

49. The need to divert underground utilities from the path of the proposed tram lines was recognised as a particular problem for the construction of any tram line through a city centre. There were usually uncertainties about the extent and precise location of utilities as records kept by utility companies were often incomplete or inaccurate. There was also unrecorded redundant apparatus relating to disconnected utilities that contributed to the congestion under ground, limiting the space available for relocation of utilities. In view of these uncertainties the diversion of utilities has tended to be an expensive part of tram or light rail schemes. Following the experience of contractors in earlier schemes to construct tram networks through city centres in the UK, tenderers were not willing to take the risk of bearing the costs of diverting utilities without adding substantial premiums to their bids.

50. The procurement strategy required the diversion of utilities in advance of the infrastructure works, to remove the uncertainty and the disruption to the programme for these works that undiverted utilities would otherwise cause for the infrastructure contractor. This strategy was intended to provide potential infrastructure contractors with an informed basis for pricing their bids, to reduce the need for risk premiums and to increase the probability of achieving the price certainty that CEC sought.

51. Instead of having utility companies diverting their own apparatus, tie planned to conclude an agreement with a single contractor who would have responsibility for the diversion of all utilities, except high-pressure mains and high-voltage power cables or other apparatus requiring the specialist involvement of the utility company owning the apparatus. Following a tendering exercise, on 4 October 2006, tie entered into the Multi-Utilities Diversion Framework Agreement (“MUDFA”) with Alfred McAlpine Infrastructure Services Limited. That company later changed its name to Carillion Utility Services Limited. At that time, this was the largest multi-utility project ever undertaken in Europe.

52. Even viewed in isolation, this element of the works itself ran over budget and took longer than expected. The effects went further than the works to the utilities, however, as the delay caused knock-on effects with the infrastructure works, which led to further delay and expense there. There were several reasons for the delay associated with the MUDFA works, including the uncertainty about the work that would be required, the delays in obtaining information from the utility companies about the location of their apparatus, the complexity of securing the consent of all utility companies to the draft Issued for Construction designs requiring the designs to be redrafted and resubmitted for approval before being issued to the MUDFA contractor, the unrealistic programme, the failure of the MUDFA contractor to relocate all utilities that had to be moved in advance of the Infraco works to construct the tram line and the inability of tie to manage such a complex contract.

53. The programme in MUDFA was unrealistic. It envisaged that the pre-construction services would be undertaken between October and December 2006 and the MUDFA works would thereafter take approximately 14 months between March 2007 and June 2008. This allowed for a gap of approximately 7 months between the programmed completion of the MUDFA works and the planned commencement of the works under the Infraco contract. The programme failed to make adequate provision for the uncertainties about the number and location of utilities in city centres at that time or for the extent of the delays experienced in other cities in the UK due to such uncertainties.