Chapter 20: Post-Mar Hall

Introduction

20.1 Resolution of the infrastructure contract (“Infraco contract”) dispute allowed work on the Tram project to resume with a new shared objective of building mutual trust. City of Edinburgh Council (“CEC”) made substantial changes to project governance. Progress was much improved. The contract works were completed approximately five weeks ahead of the revised schedule on 30 May 2014 [BFB00112249, page 0004; CEC02083198, Part 1, page 0034; Mr Foerder TRI00000095_C, page 0105, paragraph 312; Mr Eickhorn TRI00000171, page 0085, paragraph 213].

20.2 The Edinburgh Tram project (the “Tram project”) came in slightly above its revised budget: CEC agreed the budget of £776 million in September 2014, and the reported project cost as at 31 March 2017 was £776.7 million [Mr Connarty TRI00000153, page 0007, paragraph 8.2 and pages 0021–0023, Appendix 6]. That does not, however, give a complete picture of the total cost of the Tram project, which, as I will discuss more fully in Chapter 24 (Consequences), was far in excess of the reported cost of £776.7 million.

Contract

20.3 Following the Mar Hall mediation, where a settlement had been reached subject to the ratification of CEC and the boards of the members of the consortium [Mr Maclean TRI00000055_C, page 0038, paragraph 96], changes to the Infraco contract were reflected in two Minutes of Variation (“MoVs”), namely MoV4 and MoV5. As was explained in Chapter 19 (Mediation and Settlement), MoV4 was an interim and partial settlement of the parties’ dispute, including CEC’s purchase of materials from Siemens, and Infraco’s commencement in May 2011 of certain priority works. MoV5 was the principal agreement to vary the Infraco contract to reflect the agreed settlement terms. Mr Maclean provided a useful summary of the issues that had to be negotiated following Mar Hall, for incorporation into MoV5 [ibid, pages 0043–0045, paragraphs 106–124]. The first issue mentioned by him was the need to amend the defective Infraco contract. Later issues specified particular changes that were necessary. It is unnecessary to detail all the changes to the Infraco contract effected by MoV5 but of particular significance was the amendment to clause 80, which I consider in paragraph 20.12 below. It is also worth noting at this stage that following mediation there was disaggregation of Construcciones y Auxiliar de Ferrocarriles SA (“CAF”) from the consortium [ibid, pages 0043–0044, paragraph 115]. For that reason, in this chapter references to the consortium refer to BBS unless there is a particular reason to include CAF, in which case I refer to Bilfinger Berger, Siemens and CAF (“BSC”).

20.4 The changes to the Infraco contract negotiated after the Mar Hall mediation were well received. By way of example, Mr Donaldson, the construction manager of Bilfinger Berger (“BB”), said: “I never needed to look at the contract after Mar Hall. We just went out and built it. That is the sign of a good contract.” [TRI00000033, page 0022, paragraph 41.] Mr Foerder noted that, after the settlement, all relevant parties understood the contract [TRI00000095_C, page 0100, paragraph 291].

Utilities

20.5 As I have discussed more fully in Chapter 8 (Utilities), the diversion of utilities in the on-street section was far from complete even by 2011. CEC representatives at the mediation were taken aback by the scale of the task that remained, and concern about the risks still presented by utilities was a factor in the ill-fated decision by CEC’s councillors in August 2011 to stop the line at Haymarket.

20.6 The cost of utility diversions in the post-Mar Hall phase alone ended up considerably higher than budgeted and used up a substantial amount of the post-mediation risk allowance. Mr Weatherley, a director in Turner & Townsend’s Infrastructure Division, explained that the extent of the works required to the on-street utilities was not apparent until about spring 2012 when the on-street excavation had been completed. Problems emerged concerning utility works in the on-street section of the restricted route as well as works north of York Place in relation to unresolved issues from the Multi-Utilities Diversion Framework Agreement (“MUDFA”) that had been managed by tie.The scope of these works was altered and included repairs or replacement of fire hydrants, insufficient protective cover of services, insufficient separation of services, the need to replace lead water mains supply pipes and incorrect connection of gully pots. Issues with pre-mediation works mainly affected Scottish Water’s assets [TRI00000103, page 0028; CEC01891068, page 0007].

20.7 Nonetheless, the parties were able to manage the remaining utility diversions without any significant dispute or disruption to the project overall. A number of factors contributed to that result:

- the increase in resources allocated by Turner & Townsend after it took over the work stream that had previously been managed by tie;

- the relatively extensive utilities surveys carried out after the mediation under the direction of Mr C Smith and Turner & Townsend, providing a clearer factual basis for decision making;

- the “bow-wave” approach to utility diversions, with work sites being excavated to formation level and utility issues being resolved shortly before the arrival of the infrastructure contractors;

- regular meetings, providing a forum for discussion and swift resolution of utility-related problems; and

- close co-operation of the parties whose participation was necessary for the utilities issues to be resolved (clients, project managers, utility contractors, infrastructure contractors, designers, utility companies and CEC’s roads and planning departments) [see, eg, Mr Foerder TRI00000118, pages 0115–0116, paragraphs 21.3.3–21.3.5; Mr Weatherley PHT00000046, pages 43 onwards and 75 onwards; TRI00000103, pages 0024–0036].

20.8 The appointment of a dedicated utilities project manager, acting like a clerk of works, was regarded by Mr C Smith as “absolutely vital” [TRI00000143_C, page 0073; PHT00000053 pages 145–146].

20.9 An important example of the co-operation between the parties was the re-organisation of work in the Infraco programme, as part of a cost-engineering initiative, to build up a “time bank” of 22 weeks’ spare time. The time bank was built up in anticipation of utility conflicts causing delays and was in fact used up in accommodating such delays [see, eg, CEC01890999, page 0044; CEC01942252, page 0008; CEC01942260, page 0005; CEC01891022, page 0006]. This in my view serves to illustrate both the risks still presented by utility diversions to the timely completion of the project in the post-mediation period, and the manner in which a co-operative approach among the relevant stakeholders allowed that risk to be successfully managed.

Change

20.10 As has been noted in previous chapters, the change mechanism in the Infraco contract and the sheer volume of disputed change notifications prior to mediation caused significant delay to the progress of the project. Even after mediation a significant number of changes were instructed [Mr Walker TRI00000072_C, page 0086, paragraph 155]. However, there was a significant difference in the treatment of changes in the post-mediation period from their treatment prior to that. Prior to mediation both parties adopted an entrenched position, with tieseeking to resist Notified Departures, and with BSC (notably BB as the member of the consortium undertaking civil engineering works) submitting estimates at values which were in excess of what was likely to be acceptable to tie, resulting in both of them seeking support from the dispute resolution procedure. In contrast, BBS and CEC adopted a more conciliatory approach after mediation. Changes were identified, discussed and agreed in a timely manner through the control meetings, which, as will be discussed below, had been set up as part of the new governance structure for the project [Mr Weatherley PHT00000046, pages 93–95].

20.11 Change control was managed by Turner & Townsend, CEC’s appointed project manager. It reported to Mr C Smith, the project Senior Responsible Owner (“SRO”) and independent certifier. Changes were reviewed and decided upon at regular change control meetings chaired by Mr Smith, whose role included making decisions to resolve differences of opinion between Turner & Townsend and BBS. His involvement was perceived as avoiding formal disputes [Mr Easton TRI00000034_C, pages 0025–0026, paragraphs 73–80]. The effects of change were effectively managed during the post-Mar Hall period [ibid, pages 0043–0044, paragraph 136].

20.12 One of the most significant changes following mediation was the recognition that it would be necessary to modify the change mechanism in clause 80 of the Infraco contract. In that regard Mr Maclean observed:

“The problem with Clause 80 as it was in the contract was that if there was a dispute around a change and the price that had to be paid, work stopped. Work did not continue. That is why Edinburgh was a mess for months or years. That was why no one could force the consortium to get on with the Works if a dispute arose unless it was urgent. A lot of problems arose around that. That clause had to be discussed. Ultimately it was rewritten.” [TRI00000055_C, page 0044, paragraph 119.]

20.13 It is not surprising that CEC reached that view. Progress of the Infraco works had been substantially behind schedule because BSC (essentially BB) had refused to progress works until the estimates in relation to changes were agreed under clause 80 of the contract. In the adjudication about the Murrayfield underpass dispute Lord Dervaird considered the interpretation of clause 80, particularly clauses 80.13 and 80.15. He decided that tiecould not instruct BSC to commence works that were the subject of a dispute before an estimate for these works had been agreed, unless it issued an instruction to proceed with the works in terms of clause 80.15. In that event, however, tiehad to pay BSC for the works on a demonstrable cost basis.

20.14 The change mechanism in clause 80 of the Infraco contract was amended to allow CEC to instruct work to progress prior to agreement on an estimate [CEC02085623, Part 4, pages 0205–0206, clauses 80.13 and 80.15]. CEC took advantage of the new mechanism. For example, it issued Change Orders under clause 80.15 with “a not-to-exceed value to allow design works to progress”. Costs were then tracked through submission of weekly time sheets, and agreed, on a weekly basis. All estimates were agreed within acceptable timeframes [Mr Foerder TRI00000095_C, pages 0098–0103, paragraphs 287(e) and 301]. Under the new Schedule Part 45 (which applied to the on-street works), Infraco was obliged to progress works except in certain defined circumstances, which included an entitlement to suspend the on-street works if Infraco’s uncertified claims exceeded a certain level [CEC02085627, pages 0010, 0018, clause 8.1 and appendix B, paragraph 7.3]. Mr Foerder described the variation procedures under Schedule Part 45 as:

“a far more workable mechanism that [sic] the previous Schedule Part 4 and Clause 80 mechanism which had been at the centre of so many of our disputes with TIE” [TRI00000095_C, page 96, paragraph 285(e)].

Design and consents

20.15 Design and consents issues did not cause any significant problems in the post-mediation period. It had been agreed in MoV4 that BBS would self-certify compliance of the civil engineering, systems and trackworks design with the Employer’s Requirements [CEC01731817, page 0006, clause 3.5]. As soon as the parties had settled their dispute at mediation, very rapid progress was made in resolving technical approvals by CEC: between 24 March and 5 April 2011, the number of open technical approval comments was reduced from 2,782 to 85 [CEC02083973, Part 2, page 0118]. This resulted from the relocation of the CEC project management team and CEC planning and technical officials to the consortium’s project office, the allocation of increased resources within CEC and the willingness of CEC officials and BSC representatives to work seven days a week during April 2011 [Mr Foerder TRI00000095_C, pages 0098–0099 and 0103, paragraphs 287 and 304; Mr David Anderson PHT00000043, pages 191–193]. Mr Foerder also pointed to a far more open, collaborative and solution-orientated approach, and to BBS having direct contact with CEC as planning and design authority [PHT00000044, pages 161–164]. Mr Chandler said that the collaboration on design after Mar Hall was the “step change that had been missing to that point” [PHT00000020, page 111]. Similar evidence came from Mr Glazebrook [PHT00000015, page 29], Mr Reynolds [PHT00000019, page 125; TRI00000124_C, pages 0185–0186, paragraph 496] and Mr Dolan [PHT00000019, pages 208–210]. Mr Chandler thought that if a similar degree of collaboration had been present throughout the project, many of the problems could have been resolved much more easily and more quickly [TRI00000027_C, page 0172, paragraph 704]. I have little doubt that a collaborative approach involving tie, CECandBSC from the outset and throughout the project following the signature of the Infraco contract would have resolved many of the issues relating to planning consents and technical and prior approvals, but it would not have resolved the fundamental difficulties with the contract itself. The collaborative approach after Mar Hall should be seen in the context of a contract that had been fundamentally amended to remove the provisions that were an impediment to the progress of the contract, notably the change mechanism mentioned above.

20.16 In his evidence to the Inquiry, Mr Sharp had his own explanation for the rapid progress with technical approvals after the Mar Hall mediation. He suggested that, for tactical reasons, BSC and System Design Services (“SDS”) had withheld progress towards obtaining technical approvals that could otherwise have been made [PHT00000015, page 176 onwards]. Their motivation, he suggested, was to achieve a better deal on their commercial claims [ibid, page 177]. This allegation was directed at BSC and is a serious criticism of the consortium. I have given it careful consideration and have concluded that I am unable to accept it. Mr Sharp acknowledged that his view was at least “partly speculation”. Moreover, Mr Sharp’s allegation was denied by witnesses from Parsons Brinckerhoff (“PB”) who would be expected to have known about it because they would have been involved in designing solutions to concerns raised by CEC as highways authority [see, eg, Mr Chandler PHT00000020, pages 111–113; Mr Dolan PHT00000019, page 211]. Any strategy by BSC to withhold solutions from tie/CEC for tactical reasons would have necessitated the involvement of PB. I accepted the evidence of Mr Chandler that it was not in PB’s financial interests to delay reaching a possible solution to technical concerns. I also accepted his evidence that it would have been unethical for PB to collude with BSC in this way and that they would not have done so.

20.17 Under the new governance structure established after the mediation, there were weekly design and consent meetings chaired by Mr C Smith and attended by all parties having an interest in design. Mr Foerder commented favourably on the greater input from CEC than previously, as well as that of Network Rail and Scottish Water when particular issues affected their assets. He summarised the change in approach after Mar Hall as follows:

“The fact all the partners were working closely together meant that when a problem arose, everyone worked together to identify a solution.” [TRI00000095_C, pages 0091–0094, paragraphs 274 and 279–282.]

20.18 Mr Weatherley, of Turner & Townsend, described a number of areas in which design was incomplete after Mar Hall. He was, however, unable to recall any instances of a lack of design holding up construction in the post-mediation period. Utility clashes gave rise to a need to redesign works, but he could not think of any examples where that had caused any significant delay to the programme [PHT00000046, pages 63–69]. SDS’s completion of the design was held up, which it attributed to a lack of information from BBS (for example, on the trackform design), but these difficulties did not prevent construction from being concluded ahead of schedule [Mr Chandler TRI00000027_C, pages 0171–0172, paragraph 702; BFB00097924].

Non-completion of design

20.19 Although BBS agreed, at mediation, to produce an “integrated Design from Airport to Newhaven” [CEC02084685,page 0003], on 1 March 2012, CEC instructed it to stop work on the design for the section between York Place and Newhaven and to provide CEC with a status report indicating the outstanding design elements [BFB00000913]. BBS sent the relevant report to CEC on 27 June 2012 [CEC02087247].

20.20 The decision to instruct cessation of that design work was taken in the expectation that it was highly likely that a significant design review and redesign would be needed before the section from York Place to Newhaven was built, and that any new contractor would want to use its own design [BFB00000913, page 0004]. The decision does not appear to have saved cost [WED00000101, page 0006, tNC593, tCO558].

20.21 Turner & Townsend prepared a report dated 9 June 2015 relating to the proposed extension of the line from York Place to Newhaven, which noted the aspects of the design that required further work. It described them as “in the main, minor elements”, the most significant of which was the alignment design from York Place to the top of Leith Walk, including a redesigned junction at Picardy Place[CEC02087245, Part 1, page 0005]. Mr C Smith’s recollection was that the uncompleted parts of the design were peripheral, and not the core design [PHT00000053, page 174].

20.22 The Updated Outline Business Case of June 2017 for the line extension described the design for this phase as being approximately 85 per cent complete [CEC02086792, Part 2, page 0063]. It suggested that the existing design would not necessarily be wasted, as it could be provided to bidders in the form of an unwarranted reference design, which those bidders could either use (having carried out due diligence upon it) or discard. The possibility of the design being discarded does therefore raise the possibility that the expense incurred in developing it will be substantially wasted [cf the 2019 Final Business Case, CEC02087287, page 0075].

Attitudes and behaviours

20.23 Apart from the changes to the terms of the Infraco contract, the parties recognised that there had to be a radical change in the behaviour and working relationships that had blighted the project before mediation, with the emphasis being on co-operation rather than confrontation if the agreement at mediation was to result in completion of the line as far as York Place. In making that observation I do not wish to imply that all the difficulties with the previous working relationship were attributable to one party alone. These difficulties reflected the distrust that existed between the parties, for which each of them must bear some responsibility.

20.24 In implement of their desire to improve upon the past performance of the Infraco contract the parties took several different steps. Firstly, they addressed the need to improve upon the working relationship that had existed between BBS and tiebeforethe mediation at Mar Hall.The Heads of Terms agreed after mediation recorded that:

“There will be a substantive cultural shift in the behaviour of all parties including interaction, co-location and empowerment.” [CEC02084685, page 0005, clause 13.1.]

20.25 The change in attitude and behaviour was crucial to the success of the project [Mr Foerder TRI00000095_C, pages 0087–0088, paragraph 263].

20.26 Secondly, they agreed to change their management teams and working practices [CEC02084685, page 0002, clause 4.1]. Mr Walker and Mr Jeffrey left the project, as did Mr Bell (the latter after conducting a project handover to CEC and Turner & Townsend) and tieceased to be involved in the project [TRI00000072_C, page 0085, paragraph 154; TRI00000095_C, page 0100, paragraphs 290–291; TRI00000097_C, page 0061, paragraph 376; TRI00000109_C, page 0170, paragraph 146(2)].

20.27 The parties succeeded in establishing a new relationship of trust, which enabled them to work more collaboratively [see, eg, TRI00000095_C, pages 0091, 0103, paragraphs 274–275, 302; Mr Foerder TRI00000118, page 0115, paragraph 21.3.2; Dr Keysberg PHT00000036, page 72]. The minutes of the Joint Project Forum of 30 May 2012 recorded Dr Keysberg of BB as having said that the project:

“had been one of the worst projects for co-operation but within the short period since the settlement agreement it had become an example of one of BB’s best projects for co-operation.” [CEC01942270, page 0009.]

20.28 Dr Schneppendahl, of Siemens, agreed. The senior management of the consortium considered the leadership of Dame Sue Bruce and Mr C Smith at CEC to be central to the improved relationships [Dr Keysberg TRI00000050_C, page 0033; Mr Eickhorn TRI00000171, pages 0086–0087, paragraph 216.4].

20.29 Tensions still emerged from time to time, but the parties were able to resolve them. For example, on 26 June 2012, Mr C Smith sent an email requesting a meeting

“to review recent behaviours and actions in order to take us back in line, by common agreement, to that which was envisaged when we came out of mediation” [CEC01933207].

20.30 Moreover, on 8 October 2012, CEC, BB and Siemens signed a memorandum of understanding “to record and affirm the partnership working between the parties” [CEC01933565, page 0001].

20.31 The terms of the memorandum of understanding acknowledge the significant progress that had been made since mediation by “working together in the spirit of mutual respect, partnership working, cooperative and collaborative working” [ibid] and that it was necessary to maintain that commitment. The obligations specified in paragraph 2.5 of the document are indicative of the need to reinforce the commitment of parties to continue working together in a collaborative manner. The reason for the preparation and signature of the memorandum of understanding is unclear, other than that there may have been a perception that parties were not behaving as they had agreed following Mar Hall. Mr C Smith explained that this memorandum was signed around the time when he was trying to get meaningful access to the Infraco contractors’ programme [TRI00000143_C, pages 0074–0075]. That tends to suggest that BBS was not being as co-operative as one might have hoped. Mr Foerder, on the other hand, suggested that the “reset” was required because “there was a tendency for T&T [Turner & Townsend] to try and act in a similar fashion to tiepre-Mar Hall” [TRI00000095_C, page 0106, paragraph 313].

20.32 Although the above comment related to an email from Mr C Smith, dated 26 June 2012 [CEC01933207], suggesting that there was a need to “reset our behaviours” and predating the memorandum by more than three months, it confirms that Mr Smith was concerned for some time about parties failing to

co-operate to the fullest extent necessary.

20.33 I am unable to determine whether the explanation given by Mr Smith or that given by Mr Foerder is the more accurate. Having regard to the scale and complexity of the project and its ability to impact on the reputation of BBS and CEC alike, it would be surprising if there were no tensions between the parties even after their resolve to work together in a co-operative manner to achieve their mutual goal of completing the project to York Place. Whatever the causes of the perception that there was a need for the memorandum, it is sufficient to note that none of these tensions spilled into any serious dispute. The parties attributed this to the improved relationship of trust and respect, and to the new governance structure that provided a forum for difficulties to be raised, addressed and resolved [see, eg, Mr Eickhorn TRI00000171, pages 0086–0087, paragraph 216.4; Mr Weatherley TRI00000103, page 0042, paragraph 75].

Governance

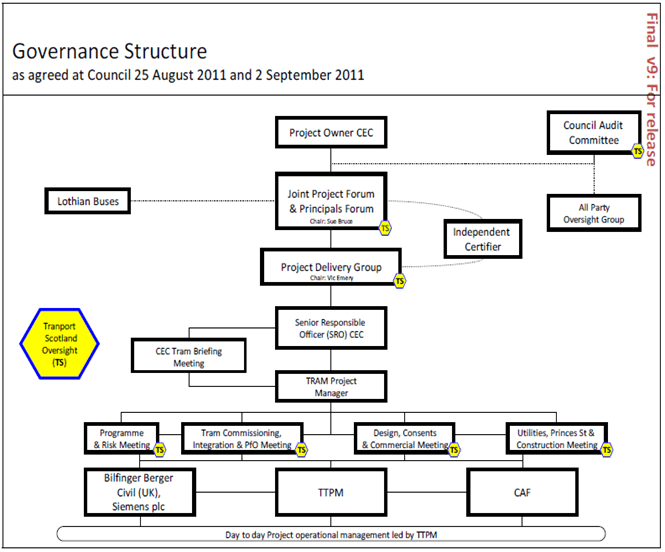

20.34 The project governance structure was significantly reformed after the Mar Hall mediation. In a report for the Council meeting on 30 June 2011 the Director of City Development (Mr David Anderson) acknowledged “the difficulties experienced in managing the delivery of the Tram project through tieLtd, as an arms length [sic], Council-owned company” [CEC02044271, page 0015, paragraph 3.81] and he proposed the revision of the governance arrangements for the project. In a later report dated 25 August 2011 to CEC’s councillors Mr Anderson noted that “The existing governance arrangements for the Tram project are complex [and] have not been effective”[TRS00011725, page 0010, paragraph 3.47].

20.35 In a report to CEC’s Audit Committee on 26 January 2012 the Chief Executive (Dame Sue Bruce) advised councillors that the new governance arrangements were in place and were set out in Appendix 1 to the report [TRS00019622]. As at January 2012, the key features of the new governance structure were as follows.

- tie was removed as CEC’s delivery agent for the project and was wound down.

- CEC took direct control of the project as employer, with tie‘s interest in the Infraco contract having been assigned to CEC on 12 December 2011.

- CEC appointed Turner & Townsend as project manager in autumn 2011. Turner & Townsend had experience in light rail projects and a number of people from that firm who had managed utility diversions in the tram projects in Sheffield, Nottingham and Croydon and who had been involved in other light rail projects, such as Dublin Metro North, were involved in the mobilisation and delivery of the Tram project [Mr C Smith TRI00000143_C, page 0078, questions 298–299; Mr Weatherley TRI00000103, page 0007, paragraph A6.3]. It was a mature organisation with “established processes and the corporate capability to adapt [its] approach to suit the needs of the tram project and to resolve issues” [Mr Easton TRI00000034_C, page 0047, paragraph 141]. This was in stark contrast to tie, which had been a new company employing freelance and contract staff as a result of which there was significant “management and staff churn” [ibid].

- CEC appointed Mr C Smith as the SRO for the project [CEC01889838, page 0002].

- Mr C Smith was also appointed as an independent certifier. In that role he was called upon to resolve any disputes that other meetings had not resolved, before escalation of those disputes to the Joint Project Forum.

- CEC established a structured hierarchy of regular meetings to address strategic and operational matters for the project. At the top of the hierarchy was the Joint Project Forum & Principals Forum, a monthly meeting chaired by CEC’s Chief Executive and attended by representatives from CEC and the consortium, with principals from the consortium being invited to attend quarterly meetings. Its purpose was “[t]o provide clear strategic leadership and direction to the project”, and to resolve issues escalated to it[TRS00019622, page 0012]. Immediately below the Joint Project Forum was the Project Delivery Group, the purpose of which was to manage the operational delivery of the project and to report on progress against programme and budget. It was chaired by Mr Emery. The Vice Chair of the Project Forum was Mr C Smith (the project SRO and independent certifier). Apart from Mr Emery and Mr Smith, the attendees were CEC’s Director of City Development, lower-ranking CEC officials, a representative of Turner & Townsend and representatives of BBS. The next level down in the meeting hierarchy consisted of regular operational control meetings, each focused on a particular topic. Once again, these were attended by representatives of both CEC and the consortium. Mr C Smith had an important role in chairing these meetings [CEC01891096, pages 0030–0036inclusive]. These regular meetings addressed such matters as: programme and risk; testing and commissioning; design, consents and commercial; construction and utilities; and communications and control. If issues could not be resolved at the control meetings, they were escalated to the Project Delivery Group.

- There were also twice-weekly senior management team meetings. One of these was the Tram Briefing meeting, chaired by the CEC Chief Executive (Dame Sue Bruce). The attendees included senior CEC officials involved in the project, Turner & Townsend and representatives of Transport Scotland. The purpose of these meetings was to provide clear operational oversight of the project to CEC as client, to provide challenge on issues and change requests, and to be the client sign-off point for change requests. The other weekly meeting of the senior management oversaw communication and stakeholder issues.

- Councillors exercised political oversight, via a monthly All-Party Oversight Group meeting, and a quarterly Audit Committee meeting. A regular meeting was set up for councillors representing city-centre wards, to keep them informed of progress and provide a formal channel for issues to be raised. In due course, tram supervision came under the remit of CEC’s new Governance Risk and Best Value Committee, set up in 2012 to be a more powerful scrutinising committee. Tram supervision also took place before the Finance and Resource Committee and the Policy and Strategy Committee [Mr Maclean TRI00000055_C, pages 0060–0061, paragraphs 179–180].

- Transport Scotland was represented at all levels of the project.

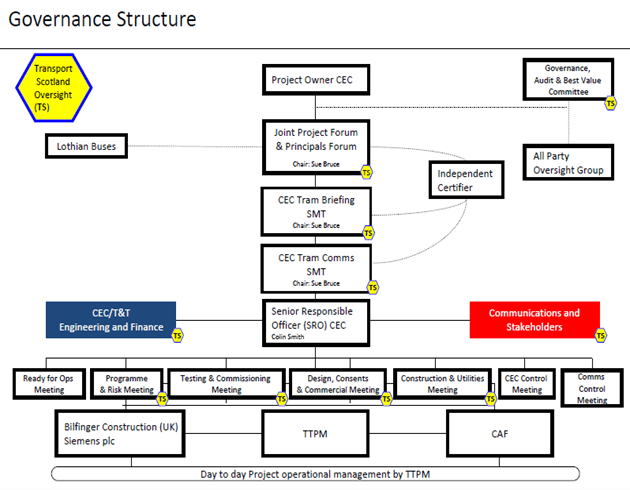

20.36 Subsequent to January 2012 it appears that there were changes to the governance structure as will be illustrated in Figures 20.1 and 20.2. The most significant change appears to be the disappearance of the Project Delivery Group as an entity. The governance arrangements following CEC’s assumption of direct control of the project were intended to reflect OGC guidance and PRojects IN Controlled Environments (“PRINCE2”) project management principles [CEC02044271, page 0015, paragraph 3.84]. The removal of the Project Delivery Group did not detract from CEC’s careful monitoring of the project and should be seen as the evolution of the governance structure, which did not have any adverse effect upon the management of the project to its completion.

Figure 20.1: Project governance structure as agreed by CEC on 25 August

and 2 September 2011

Source: Report by Chief Executive (Dame Sue Bruce) on Tram Project Update to the Audit Committee of CEC on 26 January 2012 [TRS00019622, page 0007]

Figure 20.2: Project governance structure as at 27 March 2013

Source: Joint Project Forum and Principals Quarterly Meeting, 27 March 2013 [CEC01891096, page 0022]

Discussion

20.37 The revised governance arrangements introduced in 2011 were, in my view, a very significant improvement on what had existed previously. Although the mediation had resulted in a resolution that meant that the project should be easier to administer than it had been, nonetheless, a substantial amount of construction work remained to be done and the improved governance arrangements were an important factor in that work’s being completed within the revised timetable. A number of features of the revised governance arrangements contributed to that outcome.

20.38 Firstly, the governance arrangements were simpler and clearer than those prior to Mar Hall and were easy to understand. That was in stark contrast to the previous arrangements which, as I have noted in Chapter 22 (Governance), were complicated, bureaucratic and ineffective. They lacked clear accountability and scrutiny and were not conducive to clear decision making. This view was shared by Mr Maclean. Although the previous governance arrangements pre-dated his involvement in the project, Mr Maclean had considered them in the context of the structure illustrated in the Interim Report by Audit Scotland in February 2011 [ADS00046, Part 2, page 0036]. He had concluded that it was “a convoluted corporate structure that was not conducive to clear decision making” and for that reason the governance structure was changed [TRI00000055_C, page 0052, paragraph 146].

20.39 Secondly, as promoter of the project, CEC took responsibility for, and direct control of, governance. That is most clearly demonstrated by the involvement of CEC’s Chief Executive (Dame Sue Bruce). She chaired the meeting at the apex of the governance hierarchy – the Joint Project Forum – and gave regular briefings to councillors as well as occasionally to Ministers [TRI00000084, page 0046, paragraph 148]. It is also demonstrated by the involvement of CEC officials throughout the meeting hierarchy. Mr Eickhorn, of Siemens, said that

“[t]he personnel engagement and the openness displayed by Sue Bruce, Colin Smith, and generally by CEC staff was central to the project turnaround” [TRI00000171, pages 0086–0087, paragraph 216.4].

20.40 Thirdly, CEC invested a large measure of responsibility for the project in the hands of a single person, Mr C Smith, as the SRO. Unlike Mr Renilson, Mr Smith was aware of his appointment as SRO, understood his responsibilities in that regard and he in fact performed that role. Mr Foerder considered that this was the biggest difference from the position prior to the mediation, and introduced a level of co-ordination that had not previously existed [TRI00000095_C, page 0104, paragraph 305].

20.41 Fourthly, forums for meaningful, informed and focused discussion between client and contractor were embedded into the governance structure. These meetings were appreciated by both employer and contractor. The aim was for issues to be aired in these meetings rather than in formal correspondence, thereby reducing project correspondence but perhaps more significantly, enabling matters to be raised, discussed and resolved face to face [Mr Foerder ibid, page 0097, paragraph 286(b)]. Mr C Smith used these meetings to deal with contract changes (of which there were a significant number even after settlement). These were discussed by the relevant people, who had the benefit of advice from Turner & Townsend as well as officials from Transport Scotland who were in attendance. Agreement could be reached and the decision endorsed at the next meeting, enabling progress to be made [TRI00000143_C, page 0072, question 284(B)]. It seems to me that such an arrangement is preferable to engaging in protracted correspondence, particularly in circumstances outlined by Mr Weatherley where the interaction between the diversion of utilities and Infraco was critical and the handover of sites was changing rapidly [PHT00000046, pages 96–97].

20.42 Fifthly, the meetings in the governance structure each had a clearly defined purpose, and the attendees were those with relevant expertise and responsibilities.

20.43 Sixthly, open and frank discussion of issues at these meetings was encouraged and took place, allowing solutions to be found to particular problems that arose from time to time [TRI00000095_C, pages 0096–0097 and 0103, paragraphs 286 and 303].

20.44 Seventhly, there were short reporting lines and a clear and quick escalation route for disputes [Mr McLaughlin TRI00000061_C, page 0048, paragraph 138]. Any issues that could not be resolved through the control meetings would be escalated, first, to the Project Delivery Group and, if it was unable to resolve the matter, to the Independent Certifier. If either party did not accept the Independent Certifier’s decision, the matter was to be referred to the Joint Project Forum. In the event, only a handful of matters were referred to the independent certifier for a formal decision and no issues had to go beyond him. The contract dispute resolution mechanism remained in place but was not needed after Mar Hall [Mr Foerder TRI00000095_C, page 0097, paragraph 286(d)–(e)].

20.45 Eighthly, whereas before mediation CEC officials involved with the project had other responsibilities and divided their time between the project and their other duties, the project became a dedicated project for certain officials within CEC and was no longer “a bolt on for them” [Dame Sue Bruce TRI00000084, pages 0013–0014, paragraph 42; Mr Maclean TRI00000055_C, page 0054, paragraph 152].

20.46 Ninthly, a separate forum was created, dedicated to political oversight of the project, with politicians being removed from the operational management of the project. It was described by Dame Sue Bruce as a “safe space” for open and frank discussion among councillors about the project [TRI00000084, page 0039, paragraph 123]. Councillors respected the confidential nature of the briefings [ibid, pages 0059–0060, paragraph 191].

20.47 The smooth operation of the governance structures in this period was not solely attributable to their design. An important factor was the commitment made by the main protagonists to avoid the acrimony of before. It was in their mutual interest to ensure that the restricted project was delivered. As Mr David Anderson pointed out,

“[f]ollowing mediation it was clear that both parties had a huge amount of reputational capital resting on delivering the project within the terms of the agreement” [TRI00000108_C, page 0114, paragraph 151(b)].

20.48 Dame Sue Bruce gave evidence to a similar effect [TRI00000084, page 0047, paragraph 152].

20.49 In the closing submissions on its behalf, BB identified the removal of tie from project governance as the key to the project’s success post mediation [TRI00000292 page 0276, paragraph 474]. This reflects the evidence of their project director, Mr Foerder, who described tie‘s behaviour as not being compatible with the management of such a project [TRI00000095_C, pages 0111–0112, paragraphs 331–332]. Indeed, he said that, in his 20 years’ experience of complex, international infrastructure projects, he had “never worked with people as unreasonable as the people we had to deal with at TIE” [ibid, page 0112, paragraph 334]. In its closing submission to the inquiry, Siemens said that:

“TIE was incapable of providing stakeholders with the objective financial assessment essential for good decision making. TIE’s consistently adversarial contract strategy, lack of objectivity and its outright hostility towards Infraco had merely served to delay agreement, at considerable cost to the City of Edinburgh.” [TRI00000290_C, page 0010, paragraph 17.]

20.50 It is correct that the disputes were only resolved once CEC took over decision making from tie. It is also correct that, by the end of 2010, relations between tieand BSC had almost completely broken down. However, it must be kept in mind that CEC was only able to settle the dispute because it greatly increased its budget for the project. That option was not so readily available to tie. tiehad been tasked with delivering the project inside a budget which, certainly by the time of the mediation and arguably from the date of signature of the Infraco contract, was insufficient. Attempting to work within an inadequate budget inevitably increased the likelihood of disagreement with the contractors on the operation of the contract. tiemight perhaps have managed the project differently, and achieved better relations with the contractors, if it had had the larger budget to work with. I prefer, therefore, to take the view that the resolution of the dispute by CEC agreeing to pay BSC substantially more funds than had been available to tie, and the parties’ commitment to avoiding any more acrimony, were more significant factors in the smooth running of the project after mediation than the removal of tie.

20.51 Apart from the increased budget available for the partial completion of the project and the changes in governance after Mar Hall, I also consider that the subsequent amendments to clause 80 of the Infraco contract assisted in resolving the impasse that had existed before mediation. They enabled work to continue pending agreement about the estimated cost of any change notification. Although the outcome of the Murrayfield underpass adjudication disclosed that tie had failed to understand clause 80 and, at least to that extent, supported Mr Foerder’s assertion that tie did not understand the contract, I consider that it is unreasonable to attribute all the responsibility for the earlier difficulties to tie. BSC’s submission of high value estimates for construction work that was the subject of disputed change notifications should also be seen as a contributory factor in the difficulties in the relationship between them.

20.52 The removal of tie did, however, bring CEC closer to the project, and that had benefits. This was acknowledged by Dame Sue Bruce, who explained the rationale for removing tie as follows:

“The Council was carrying the risk and I strongly believed that they needed to have more control over what was happening in order to manage that risk.” [PHT00000054, page 6.]

and Dame Sue Bruce recognised that CEC was the project owner, and was therefore accountable for its delivery, whereas tiewas responsible for its delivery. She considered that the link between responsibility and accountability had been broken [TRI00000084, pages 0006–0007, paragraph 21]. I agree with that view. The removal of tiemeant that CEC had both responsibility for delivery of the project and accountability. It resulted in shorter reporting lines and enabled decisions to be taken directly by the project owner, resulting in more efficient management of the project. For completeness I should note the evidence of Mr Maclean about CEC’s Corporate Programme Office (“CPO”) [TRI00000055_C, pages 0052 and 0058–0059, paragraphs 147 and 173–175]. Following his appointment as Director of Corporate Governance in 2011, in 2012 Mr Maclean established the CPO in response to failings in various projects including the Tram project. Its purpose was to supervise major projects, and ensure that they were governed properly and completed on time and to budget. Although the Tram project was excluded from the CPO’s remit because it was perceived as needing its own “intensive care”, it reflects the lack of adequate oversight by CEC of major projects at that time, including the Tram project, for which it was accountable. Mr Maclean observed that if the CPO had been established and if CEC had been running the Tram project “it would have noticed the poor management/governance issues that arose” [ibid, page 0059,paragraph 175]. Before the establishment of the CPO he explained that “CEC was, in many ways only overseeing the project”. tiewas running and project managing the projectbut there were issues within CEC relating to internal control and its failure to take more control over tie. This evidence clearly recognises that it is over-simplistic to place all responsibility for the failure of the project upon tieand that CEC bears much of that responsibility because of its failures mentioned by Mr Maclean.

Independent certifier

20.53 At the Mar Hall mediation, BBS had sought the involvement of an independent certifier to determine disputed issues of principle and quantum under the contract.

In his evidence to the Inquiry, Mr Eickhorn, of Siemens, stated:

“I believe an Independent Certifier was needed as there had been so many disputes in respect of payment falling due and the agreement of Estimates. It was thought that it would assist to have an impartial view to avoid such disputes happening in the future.”[TRI00000171, page 0065, paragraph 144.]

20.54 Mr C Smith was appointed as the independent certifier, first in relation to the prioritised works carried out under MoV4, and later for the remainder of the project. His appointment as the independent certifier when he was the SRO raises an issue about the appropriateness of such an appointment when one might expect an independent certifier to be seen to be independent of all parties involved in the project. It is not clear why the consortium considered Mr Smith to be sufficiently independent of CEC or impartial: he had come into the project as an adviser to Dame Sue Bruce, and had a prior history of working with her. Furthermore, he held the position of SRO on behalf of CEC from at least August 2011. It was unusual for someone in that position to fulfil the role of an independent certifier [Mr David Anderson PHT00000043, page 194]. Nonetheless, it is clear that the consortium trusted Mr Smith, and appreciated his contribution to the project. In that regard

Mr Eickhorn observed:

“Colin Smith who was appointed as the Independent Certifier managed to hold together many loose ends and did an effective job of managing the stakeholders and maintaining control of the project.” [TRI00000171, page 0093, paragraph 237.2.]

20.55 The above comment does not seem to me to distinguish clearly between Mr Smith’s role as Independent Certifier and his role as SRO. Mr Smith himself did not make much distinction between the two roles and he did not consider that any decisions he was called upon to take as independent certifier were in conflict with CEC or his SRO role [PHT00000053, pages 147–152]. However, as SRO, Mr Smith owed duties solely to CEC, while, as independent certifier, he owed duties both to CEC and to the consortium companies and was obliged to act independently and impartially as between them [BFB00005677, pages 0005–0006, clause 3]. BBS’s payment applications were submitted to Turner & Townsend on behalf of CEC and to the independent certifier at least seven days before the valuation date. Thereafter a meeting was to be held to discuss the application for payment, following which the independent certifier was to issue a valuation certificate [ibid, page 0007,clause 5]. In the event of any difference of opinion between Turner & Townsend and BBS that had not been resolved, as independent certifier Mr Smith would be called upon to adjudicate and to make his own assessment [Mr Weatherley TRI00000103, pages 0044–0045, paragraph A82].

20.56 Mr Emery said that he had concerns that Mr Smith’s dual role involved a conflict of interest, and that he had made these concerns known to Mr Maclean and Dame Sue Bruce. According to Mr Emery,

“[their] answer was: well, he is proven to be very good at what he does. He can be independent. He is the SRO. We needed to have someone to hold Turner & Townsend to account, but also to facilitate any disputes that were going on between the project group and the contractor. So there was a great deal of confidence placed in the independent certifier.” [PHT00000052, pages 112–113.]

20.57 This response confirms the need for an independent certifier to help resolve any disputes about payment as quickly as possible. However, it fails to address the apparent conflict of interest between Mr Smith acting on behalf of CEC as SRO and adjudicating in disputes about applications for payment between BBS and CEC’s project managers. As is noted below, the conflict of interest could have resulted in a disadvantage to either party, including CEC.

20.58 Mr Emery thought that if Mr Smith had reached a decision that, viewed objectively, was not in the interests of CEC, probably no one else at CEC would have challenged it, although others within the governance structure might have done [ibid, page 115]. Mr Emery cited instances where the advice of Turner & Townsend was overruled by CEC’s executive, based on the view of the independent certifier (although he did not say that either CEC’s executive or Mr Smith were wrong in what they did) [ibid, page 117]. His assessment that nobody at CEC would have challenged Mr Smith’s decision as the independent certifier is consistent with the confidence that members of the executive, particularly the Chief Executive, had in Mr Smith and with the impression that they were anxious to bring the partial project to a completion following mediation. Viewed objectively, Mr Smith’s dual role as SRO and independent certifier did not give the appearance that CEC had taken all necessary steps to protect its interests as well as the public purse.

20.59 Under questioning, Mr Smith came to accept that his dual role gave rise to a potential perception of conflict of interest, although he pointed to the fact that there were no complaints about his performance [PHT00000053, page 149]. In determining whether there was a conflict of interest, actual or perceived, it is irrelevant whether there had been any complaints about his performance. In its closing submissions, CEC acknowledged that in an ideal world it was not best practice for the SRO also to be an independent certifier. The explanations tendered in the submissions for the departure from best practice were that Mr Smith himself thought that nobody would have been reluctant to challenge his decisions if they disagreed with them or that all parties were happy with the arrangement and that it did not cause any problems or any increase in cost [TRI00000287_C, page 0514, paragraph 21.22]. These explanations fail to acknowledge the potential for such consequences arising from the dual appointment. Having regard to the care and attention that parties gave to reforming the poor governance structure of the project that had existed prior to mediation, it is surprising that they failed to appreciate that having the same person performing the roles of SRO for one of the parties and independent certifier was itself an indication of poor governance.

20.60 Although several witnesses were complimentary about Mr Smith’s work and considered him a positive influence on the project [see, eg, Mr Gough TRI00000295, page 0005, paragraphs 32–34; Mr Eickhorn TRI00000171, pages 0086–0087, paragraph 216.4; Dr Keysberg TRI00000050_C, page 0033, answer 37(a); Mr Weatherley PHT00000046, page 75], the impression that I gained from the evidence on this matter was that it was the change in governance and the involvement of Dame Sue Bruce as well as Mr Smith that turned the project around. It was also apparent that there was a consensus that the appointment of an independent certifier had been an advantage, but I was unsure whether parties had given any consideration to an independent person undertaking that role. If that had occurred, the advantages of having an independent certifier would have been achieved without the potential disadvantages associated with Mr Smith fulfilling that role. I have come to the view that it was inappropriate for Mr Smith to hold both roles. It is not possible, as a matter of principle, simultaneously to perform fully, on the one hand, a role that requires one to act in the interests of all parties and, on the other hand, a role that requires one to act in the interests of one of them. This would most obviously present a risk of decision-making against the interests of the consortium. However, they were experienced commercial entities who were obviously happy with Mr Smith’s work. If they had been aggrieved by his decisions, they could (and no doubt would) have challenged them, but they did not do so.

20.61 The conflict might equally, however, have operated to the disadvantage of CEC. The most obvious situation in which this might arise is one in which the certifier has adjudicated on a disagreement between the parties. Having done so, he could not thereafter form the view that his decision wrongly favoured the consortium. It is possible that a person engaged to act for both parties would prioritise the avoidance of dispute over cost control, which might be in the interest of the employer alone. My concern is that, within CEC, there might have been insufficient potential for challenge to Mr Smith’s decisions as independent certifier. That would create the risk that, on matters of commercial disagreement between the consortium and CEC, some resolutions might be too favourable to the consortium. That risk is all the greater where the project’s history made CEC keen to avoid disputes.

20.62 Mr Smith explained in evidence that none of his decisions as independent certifier was challenged. On one view, that is a good thing, indicating consensus-based progress of the project. In my view, however, it is not surprising that CEC’s executive did not challenge Mr Smith’s decisions, given that he also held the role of SRO. Mr Smith’s response was that there were a number of people on CEC’s side of the project who could have taken issue with his decisions. These included Mr Sim, Mr McCafferty, Mr Coyle, Mr Maclean, officials from Transport Scotland and Turner & Townsend [PHT00000053,page 150]. None of these, however, had the combination of professional expertise and seniority on the project that Mr Smith had. Mr Smith pointed to Mr Easton and Mr M Mackenzie from Turner & Townsend as being able to articulate in detail any nuance that he had overlooked [ibid, page 151]. That is no doubt correct. However, the reality is that they would have articulated a position for CEC on a matter before Mr Smith took his decision on it as independent certifier. It is also true that, higher up the governance structure, decision-making responsibility lay with Dame Sue Bruce. She was not, however, a construction professional and had herself brought Mr Smith into the project so that she could benefit from his technical expertise. I find it difficult to accept that she would have been likely to challenge his decisions.

20.63 Mr Smith explained that it was not his style to issue decisions with a warning, implicit or explicit, not to challenge him [ibid, page 152]. I am perfectly willing to accept that this was not his style, but that is beside the point. The fact that he held the dual roles of SRO and independent certifier meant that there was a risk that the protection of CEC’s interests on commercial aspects of the project was diminished.

Political oversight

20.64 The post-Mar Hall governance arrangements drew a clear demarcation between execution of the project and political oversight. Councillors were briefed about the project, and given the opportunity to scrutinise it, in forums specifically designed for that purpose. They were not involved in project execution or operational decisions, in relation to which CEC’s functions were carried out by officials and professionals appointed to act on their behalf. That stands in contrast to the arrangements prior to the settlement, under which some councillors were members of the Tram Project Board and sat as directors of tieand TEL.

20.65 In his evidence to the Inquiry Mr Emery said that it was never appropriate to have political representatives on the project boards for projects of this type. As he put it, “I think the politics should be done at a different arena, not on a project delivery arrangement” [PHT00000052, page 117]. He cited the problems of political disagreements causing delay in the running of the project, and of leaks to the media of information that should have stayed within the client organisation.

20.66 Mr David Anderson said that in all the other construction projects that he had been involved in, there had been a much clearer separation between the strategic role performed by political representatives and the project delivery function of officials than there was on the Tram project prior to the Mar Hall mediation [TRI00000108_C, page 0129, paragraph 162]. He also noted that, in other projects that he had worked on, there had been political consensus about the need for investment [ibid].

20.67 Mr McGougan said that political consensus was important for long-term infrastructure projects. In view of the duration of infrastructure projects such as the Tram project he suggested the development of a national infrastructure plan, and that the support of all political parties for its contents be secured so far as possible. He referred to a non-political infrastructure commission having been set up in England and suggested that a similar body could be considered in Scotland [TRI00000060_C, page 0150, paragraph 390]. The UK National Infrastructure Commission was established in 2015. In 2019, following the conclusion of the evidential hearings, the Scottish Ministers established the Infrastructure Commission for Scotland (“the Commission”). The work of the Commission will assist the Government in formulating a long-term infrastructure strategy to meet the country’s needs.

20.68 Councillor G Mackenzie, a former convenor of the Transport, Infrastructure and Environment Committee and member of the TPB, doubted that, as a public forum, a council was the right body in which to discuss such things as strategy or tactics in relation to disputes, or figures. Discussions about such matters would disclose information that would be of value to the contractor and detrimental to the Council’s interests. In that regard he identified a tension between the democratic nature of a local authority and the proper management of a project that required engagement with a commercial entity. Commenting on the changes in the involvement of councillors after mediation, he observed:

“Later on, after the mediation, CEC officers effectively took Councillors out of the loop. Councillors got a very restricted update on what was happening and from the point of view of running it on a commercial basis that seemed far better, in my opinion, although from a democratic point of view it was not.” [TRI00000086_C, page 0126, paragraph 385.]

20.69 The reference to councillors getting a “very restricted update on what was happening” contrasts with the evidence of Mr Maclean, mentioned in paragraph 20.70. Councillor G Mackenzie’s reference to the arrangement being unsatisfactory from a democratic point of view might suggest that he still fails to appreciate the distinction between councillors requiring sufficient information to enable them to take strategic decisions and officials taking executive decisions to implement the strategy. It is unnecessary for councillors to know the details of such executive decisions as long as such decisions comply with the strategy and the project is on time and within the budget approved by councillors.

20.70 Mr Maclean explained that, after the settlement, tram reports went to a range of executive committees of the Council, namely the Finance and Resources Committee, the Policy and Strategy Committee, and the Governance, Risk and Best Value Committee (“GRBV”). GRBV considered an update on the progress of the project every two months and was given “full detail as to costings”. The reporting to these committees was clear and regular, and allowed better scrutiny than had been possible with ad hoc reports to the Full Council [TRI00000055_C, pages 0060–0061, paragraphs 178–180].

20.71 In my view, there is a clear, and generally recognised, distinction between the proper roles of councillors and officials. The role of politicians, for which they are accountable to the electorate, is to set policy and to take strategic decisions. In general, it is not a proper part of their remit to manage, implement or operate a project. That is the role to be carried out by the officials themselves or through the engagement of suitably qualified third parties or a combination of these two options. It is unlikely to be helpful for councillors to participate in those activities. Doing so would risk almost certain conflict with the proper exercise of their political functions. Councillors must, of course, be kept informed about the project, so that they can scrutinise the implementation of their policy and set new policy objectives if that is appropriate. In my view, the way in which the post-Mar Hall governance structure provided for political oversight of the Tram project was a sensible way to do this and was much improved from the way in which it had been done before. I reject Councillor G Mackenzie’s suggestion that it was unsatisfactory from a democratic viewpoint.

20.72 I add that it is likely to be disruptive to the smooth running of a major project if the policy behind it remains, or becomes, controversial after contractual commitments have been made. Policy divisions among politicians are liable to undermine stable management of the project. There will be a tension between the democratic imperative to debate policy divisions in public, and the commercial imperative to keep one’s negotiating objectives and tactics private. Sometimes, the eruption of policy divisions mid-project will be unavoidable: circumstances may change in unexpected ways and policy may have to be revisited in response. Nonetheless, the aspiration should clearly be, so far as possible, to fix the policy objectives before any contractual commitments are made. The involvement of the Commission in informing policy might assist in achieving political consensus about proceeding with the scheme before the commitment of substantial amounts of public expenditure.

20.73 Furthermore, the need for a stable policy foundation points to the need for the politicians making the policy commitment to be given a clear and transparent basis for doing so. If their policy commitment rests on an inadequate assessment of the risks, for example, the scene will be set for a destabilising policy debate as and when those risks transpire once the project is under way.

Transport Scotland involvement

20.74 The new governance structure provided for the involvement of Transport Scotland at all levels [CEC01891096, page 0022]. Its re-engagement was a response to the decision of CEC’s councillors, in August 2011, against their officials’ recommendation, to stop the line at Haymarket [TRI00000061_C, page 0029, paragraph 77]. It also followed Audit Scotland’s suggestion, in February 2011, that the Scottish Ministers consider whether Transport Scotland should become more actively involved in assisting the project [ADS00046, Part 1, page 0009].

20.75 CEC and the Scottish Ministers entered into an agreement setting out the terms for Transport Scotland’s re-involvement [TRS00014693]. It provided for Transport Scotland to give advice and direction to assist CEC in delivery of the project, with the involvement of Transport Scotland officials. The level of Transport Scotland’s involvement is illustrated by the terms of the agreement. Ministers were to be represented by Transport Scotland’s Director of Major Infrastructure Projects or such other person as Ministers may nominate as a Project Director who was to be assumed into the governance arrangements at a position to be determined by Ministers in consultation with CEC. Ministers could also deploy other Transport Scotland officials throughout the governance arrangements at positions to be determined by Ministers in consultation with CEC and CEC was obliged to assume these officials into the governance arrangements. The Project Director was entitled to employ external consultants to support Transport Scotland officials and to give directions to CEC, which CEC had to implement unless they would cause CEC or tieto be in breach of contractual or statutory duties. The cost of the involvement of Transport Scotland, including the costs of its officials and any external consultants, was to be met by CEC.

20.76 Mr McLaughlin was the project director appointed by Scottish Ministers and was part of the senior management team for the project. He was supported by a senior project manager/engineer with a small team of about three from Transport Scotland who worked alongside CEC. He described Transport Scotland’s involvement as “collaborative”, helping CEC where it could. He referred in particular to “adding some Ministerial weight to getting cooperation with the service and utilities companies” [TRI00000061_C, page 0029, paragraph 78, see also pages 0041–0042, paragraph 117]. For example, Mr McLaughlin and Mr Neil (the Cabinet Secretary for Infrastructure and Capital Investment) met utility company heads to seek their further co-operation with the Tram project [CEC01889528, page 0003]. Mr McLaughlin also said that Transport Scotland provided help with the management of contractual risk and the interface with its works at the Edinburgh Gateway station at Gogar [TRI00000061_C, page 0030, paragraph 81]. The involvement of Transport Scotland facilitated access by CEC to Ministers [Mr Maclean TRI00000055_C, page 0064, paragraph 191].

20.77 Witnesses were generally complimentary about Transport Scotland’s involvement. For example:

- In a report to Council dated 25 October 2012, Dame Sue Bruce described the involvement of Transport Scotland in the project as “extremely positive” [CEC01891499, page 0002, paragraph 2.2.1].

- Mr C Smith considered it to be a “sounding board”, and that it brought gravitas. Its involvement helped with discussions with Network Rail in relation to construction near the railway line and with Scottish Environment Protection Agency about its concerns of possible contaminated material in stockpiles taken from railway embankments [PHT00000053, pages 176–177].

- Mr Maclean described Transport Scotland’s role as “primarily observing”, and thought “there was no discernible difference following TS’s increased involvement” [TRI00000055_C, pages 0063–0064, paragraphs 189–190]. This was in contrast to the views expressed by the Scottish Ministers or the media. Nevertheless, broadly, he thought that it was good to have it involved [ibid, page 0064, paragraph 191]. He considered that its removal from the project in 2007 had been a tactical error [ibid, page 0051, paragraph 144].

- Mr David Anderson said that Mr McLaughlin’s contribution was “exceptionally helpful throughout” [PHT00000043, page 209].

- Mr Emery thought that Transport Scotland assisted the project, and that it brought good advice on project management to the Project Delivery Group that he chaired. In addition, its involvement in the construction of the interchange at Edinburgh Gateway, to enable an easy transfer of passengers from the Fife rail line to the tram at Gogar, meant that there was a mutual interest there between CEC and Transport Scotland [PHT00000052, page 121].

- Mr McLaughlin agreed that Transport Scotland’s involvement was positive, and that it brought knowledge and client expertise to the project [PHT00000011, pages 204, 206, and 227].

- Dr Keysberg said that “Transport Scotland once they became involved were extremely professional and helpful” [TRI00000050_C, page 0033, paragraph 38(b)].

20.78 The positive comments mentioned in paragraph 20.77 about the renewed involvement of Transport Scotland in the project after mediation should be seen from the perspective of those involved in the completion of the curtailed project within the revised budget and timescale agreed after Mar Hall. When one considers that involvement from the perspective of Scottish Ministers and Transport Scotland, the terms of the agreement mentioned in paragraph 20.75 above illustrate that Ministers intended Transport Scotland to take an active role in the governance of the project and gave it powers of direction that CEC had to implement unless it would result in CEC or tiebreaching contractual or statutory duties. The nature of Transport Scotland’s involvement, including its powers of direction, and its apparent success in securing the completion of the curtailed project on time and ostensibly within the budget of £776 million, reinforce my views, expressed in Chapter 3 (Involvement of the Scottish Ministers), that it was a serious error of judgement to withdraw Transport Scotland from the project following the parliamentary rejection of Ministers’ proposal to abandon the project. Had that error of judgement not occurred it is probable that the Infraco contract would not have been signed in 2008 and there would not have been the level of wasted public expenditure that ultimately occurred.

20.79 I consider that the experience of the project illustrates the need for Ministers to give serious consideration to the active involvement of Transport Scotland in the governance of any future light rail projects at the construction stage to the same extent and with the same powers of direction as it had after Mar Hall, as well as in the earlier stages leading to the conclusion of the construction contract. Such an involvement is undoubtedly necessary where the Scottish Ministers are the principal funders of the project and wish to protect the public purse and to ensure that their investment delivers the promised benefits of the project on time and within budget. However, even where such projects are funded by a local authority without any direct grants from the Scottish Ministers, there may be merit in the involvement of Transport Scotland to the same extent. In the latter case the local authority would have access to the public-sector experience and expertise within Transport Scotland.

Stakeholder forum

20.80 The revised governance structure after Mar Hall included a stakeholder forum or the External Stakeholder Group. It was intended to allow CEC, as project promoter, together with the contractors, to manage key relationships with stakeholders directly impacted by the project, including Edinburgh Airport, Henderson Global Investors (the promoters of the redevelopment of the St James Centre), business groups such as Edinburgh Business Forum, the Federation of Small Businesses and the Edinburgh Chamber of Commerce, as well as representatives of local communities [CEC02044271, pages 0016 and 0025–0026, paragraph 3.91 and appendix 2]. However, as will be discussed more fully in Chapter 24 on the consequences of the project being curtailed, delayed and over budget, the initial proposals were inadequate.

Surplus tram vehicles

20.81 As will be discussed in Chapter 24 on the consequences of the failures in the project, unnecessary public expenditure was incurred in the purchase of an excessive number of tram vehicles (27), assessed in the evidence of Mr C Smith and in the closing submissions on behalf of CEC as being between seven and ten [PHT00000053, page 177; TRI00000287_C, page 0305, paragraph 7.47], although a report to CEC in 2011 estimated the excess at between six and ten [CEC01914650, page 0009,paragraph 3.20]. The vehicles had been purchased on the basis that it was intended to construct a line between the Airport and Newhaven but were more than was required to serve the truncated line between the Airport and York Place. The subsequent construction of the line from York Place to Newhaven enabling the surplus trams to operate as originally intended will mitigate the wasted expenditure but will not eliminate it (see paragraph 24.76). Although this issue will be considered in Chapter 24 on consequences in the context of unnecessary expenditure, it is appropriate to recognise the steps taken by CEC to mitigate the level of unnecessary expenditure.

20.82 Retaining the surplus vehicles was the least-favoured option: while it allowed the system’s total mileage to be spread across a larger fleet, provided spare capacity and was a source of spare parts, the costs (financing, depreciation, insurance and maintenance) were said to be greater than the project needed to incur [CEC01890999, page 0059]. The possibility of using the vehicles for early-morning freight deliveries was considered in November 2011 by the Joint Project Forum but required further investigation [CEC01890994, page 0007].

20.83 CEC investigated what, if anything, could be done to realise value from the surplus vehicles. Those investigations did not lead to any value being realised. The steps taken included:

- making an unsuccessful bid with CAF to lease the vehicles to Transport for London for the Croydon Tramlink [CEC01914650, page 0009, paragraph 3.21].

- investigating leasing the trams out via Rolling Stock Operating Companies, but concluding that demand was not likely to exist [ibid, page 0073, paragraph 3.41 onwards].

- assessing potential demand for the Edinburgh vehicles from other tram systems elsewhere in the UK, in Turkey and in Norway, but concluding that funding for the UK systems was uncertain, the extent of opportunities in Turkey was unknown, and the Norwegian option would have required extensive modification works to the trams for only a short period of use [ibid, page 0074].

- an inquiry for the tram vehicles from Australia was considered, as was their use

on the new Borders rail line [CEC01890068, page 0006, item 5; CEC01891352, page 0001, item 1]. - Mr C Smith asked CAF whether it would buy the trams back. CAF made an offer in relation to ten trams, but nothing came of that initiative [CEC01891088, page 0014; PHT00000053, page 177; TRI00000143_C, page 0103, paragraph 345].

Completion and final costs

20.84 Following the Mar Hall mediation, CEC set a revised project budget of £776 million [TRS00011725, page 0003, paragraph 3.13; see TRI00000153, page 0019, Appendix 5, for a breakdown]. A statement to the Inquiry by Mr Connarty, a qualified accountant and senior manager in CEC reporting to the Head of Finance, noted that, as at September 2017, the cost of those items that had been included in the £776 million budget stood at £776.7 million [ibid, pages 0007 and 0021–0023, paragraph 8.2 and Appendix 6]. These headline figures demonstrate that the project came in slightly above the post-Mar Hall budget. The underlying figures reveal, in some categories, significant variances between the budgeted costs and the actual costs [ibid, pages 0007 and 0065, paragraph 7.1 and Appendix 17].

20.85 The greatest increases over the post-Mar Hall budget were as follows:

- infrastructure (Infraco): £402.1 million to £419.8 million (+ £17.7 million, or + 4.4 per cent);

- utilities (post-mediation): £2.9 million to £20.5 million (+ £17.6 million, or + 606 per cent);

- project management: £83.1 million to £90.2 million (+ £7.1 million, or + 8.5 per cent).

These increases were offset by savings from the budgeted costs in other areas, including the “Readiness for Operations” and “Land, Property and Other Costs” categories. The main impact of the cost increases, however, was that the contingency allowance, £34 million out of the £776 million budget, was spent in full [ibid, page 0065,Appendix 17].

20.86 Furthermore, additional costs were incurred in relation to the Tram project, beyond those accounted for as part of the £776 million budget. A full understanding of the cost of the project requires that these also be taken into account. Mr Connarty explained that certain matters were outstanding but that he did not anticipate a material change in the final reported cost [ibid, page 0003, paragraph 5.4]. As will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 24 on the consequences of the delays to, restricted scope of and increased costs of the project, the additional costs of resolving outstanding matters amounted to £4.456 million, resulting in a reported cost of £781.118 million. However, apart from the additional costs of resolving disputes further additional costs were detailed by Mr Connarty and discussed in Chapter 24, which resulted in the project’s total cost being £852.591 million after discounting future borrowing costs to a net present value. To gain a fuller understanding of the project cost the following paragraphs consider the composition of the reported cost of £776 million and thereafter compare the figures for the component parts with their equivalent figures at financial close.

Costs within the £776 million Tram project budget

Infraco contract works, including changes

20.87 The post-mediation budget for the Infraco works was £402.06 million [ibid, page 0019, Appendix 5]. This was made up of:

- £360.06 million for the off-street works;

- £38.8 million for the on-street works; and

- £3.2 million for maintenance, mobilisation and spare parts. [WED00000092,

page 0003, which is Turner & Townsend’s commercial summary in its final

Infraco Cost Report; Mr Easton TRI00000034_C, page 0031, paragraph 99.]

20.88 The post-mediation contract price for the Infraco works was £413,102,911.41 [WED00000101, page 0004, which is Turner & Townsend’s Infraco Final Account; Mr Easton TRI00000034_C, page 0031, paragraph 99]. That was made up of £362,500,000.39 for the off-street works; £47,384,510.07 for the on-street works; £2,205,310.95 for maintenance mobilisation; and £1,013,090 for spare parts [WED00000101, page 0004].

20.89 The budgeted costs of the on-street and off-street works were therefore lower than the contract prices. In the case of the off-street works price, the difference is that the budget took into account the de-scoping of certain works in the Forth Ports area, which was subsequently implemented by a contract change [CEC02086442, page 0001; WED00000101, page 0005, tCO528]. In the case of the on-street works, the budgeted price appears to have assumed that certain value engineering opportunities would be achieved [CEC02086442, page 0001].

20.90 The total cost of the work by BB and Siemens under the Infraco contract was £427,206,309.52 exclusive of VAT [WED00000101, page 0003; Mr Connarty TRI00000153, page 0028]. The price had increased from the post-mediation contract price because of changes: a net increase of £4,295,156.90 due to changes under schedule 45, being the schedule that concerned the on-street works, and a net increase of £9,808,241.21 due to changes under clause 80, which applied to the other contract works [WED00000101, page 0004; on the distinction between clause 80 and schedule 45, see Mr Foerder TRI00000095_C, pages 0095–0096]. The total net value of these changes was £14,103,398.11.

20.91 Notable, or significant, post-settlement agreement changes included the following.

- The increase of £4.541 million attributable to the delay caused by the Council’s decision in August 2011 (reversed in September 2011) not to approve the recommended option of a line to York Place.

- The increase of £6.460 million attributable to the creation of the 22-week “time bank”.

- An increase of £3.263 million for the construction of the Edinburgh Gateway, as part of Transport Scotland’s project for an interchange for trains travelling from Fife. This was funded by a separate Transport Scotland grant [TRI00000153, page 0024, Appendix 7].

- A deduction of £2.433 million for the omission of works in the Forth Ports area.

- A deduction of £2.156 million for the omission of work at St Andrew Square and

St David Street. - A deduction of £1.1 million for cancelled trackwork materials relating to the stretch between York Place and Newhaven.