Chapter 21: Risk and optimism bias

Risk and Optimism Bias

21.1 It is not unusual to hear of construction projects that have gone dramatically over budget. Risk – or the danger that there will be events that result in delay or in costs increasing – is a fact of life well known to those involved in such projects, including the personnel at tie Limited (“tie”). A number of measures may be taken in response, which can be grouped into the following four categories.

(1) Elimination of risk

(2) Transfer of risk

(3) Minimisation/control of risk

(4) Quantification of risk

21.2 In the Tram project tie had a risk policy and advisers were engaged to assist in management of risk [Mr Bourke PHT00000022, pages 3 and 5]. tie set out to use measures falling into each of the categories above to some extent, but it is apparent that ultimately it was not successful, and it is necessary to consider why that was.

21.3 Before doing so, for completeness, I should note two areas of risk management that I do not consider further in this chapter. The first is that, in addition to measures from the four categories above, tie had put in place insurance in respect of risks arising from liability as employers or owners of property. However, as this does not address the costs of the works as such, I do not consider it further. The second area is the legal structure required of the parties in order to undertake the work. From the outset, it was part of the procurement strategy that the various broad components of the works (design, infrastructure and tram vehicles) should be procured individually. The view was that this would encourage more competitive pricing and ensure the lowest possible cost. However, having the various elements of the works under different contracts gave rise to a risk that, if there was delay or defective performance under one contract, the party to one or more of the others would claim that it affected their ability to carry out the works or would result in additional cost under their contract. Ensuring that each contract was properly managed so that it delivered the required outcome at the correct time was therefore critical. There was, to some extent, an inevitable trade-off between getting the best price and accepting risk. The intention was that this could be addressed by requiring that the parties undertaking the infrastructure works and supplying the trams do so as a consortium. The advantage of this is that each member of it would be liable for any failure, whether it was by it or a consortium partner. This approach was taken further in the intent that the design contract be novated to the consortium. This legal device had the effect that all the rights and obligations as between tie and Parsons Brinckerhoff (“PB”) would be transferred to be between the consortium and PB and that all the work that had been undertaken by PB prior to the novation would be deemed to have been done under the replacement contract between PB and the consortium. The intention of this was that tie would be able to look to the consortium in the event that there were problems with the design, leaving the consortium to seek redress from PB. In fact, the design was so far behind schedule that it made it difficult for tie to gain the benefit of novation to Bilfinger Berger, Siemens and CAF (“BSC”). Also, because the design was not finished at the time that the novation took place, it meant that if PB made a change to the design, it would constitute a Notified Departure in terms of the infrastructure contract (“Infraco contract”), which would entitle the members of the consortium to additional payment. It also resulted in the situation in which BSC was responsible for managing PB while being in the position of getting additional money if there was a design change.

21.4 Mr Bourke, a risk manager who was employed by tie from 2003 to 2007, explained that previous tram projects had been studied and an attempt had been made to identify the lessons that could be learned from them [ibid, page 20]. This gave rise to a number of strategies aimed at eliminating risk. Perhaps the most significant measures to come from this were the original intent that the design for the infrastructure works would be fully complete by the time that a price for those works was agreed, and that the works to divert utilities would be carried out under a different contract and would be complete before the Infraco works got under way [see draft Final Business Case (“FBC”), November 2006, CEC01821403, pages 0017–0018, 0085 and 0090, paragraphs 1.80, 7.53 and 7.77]. Mr Bourke agreed that in these respects the strategy hinged on achieving the right design at the right time [PHT00000022, pages 9–10]. Although these were seen as important elements of the procurement strategy, it is apparent that they were not implemented, and that is the simple answer to why this element of the strategy was not successful in removing risks. I have considered these matters earlier in this Report (see, e.g., 5.86; 6.118–6.123; 12.54).

21.5 As the risks had not been removed, the next issue was whether they could be transferred to the contractors. This was the intention within tie in relation to the risk arising from the incomplete design, and it was this that led to the discussions in Wiesbaden. However, as was noted in Chapter 12 (Contract Close), both the written agreements that followed those discussions, namely the “Agreement for contract price for phase 1A” [CEC02085660, Parts 1–2] and “Schedule Part 4 – Pricing” (“SP4”) [USB00000032] left substantially the entire risk with tie, as it was the intended purpose, as well as the effect, of each of the pricing assumptions in SP4 to allocate to tie the risk in the event that the circumstances were not as assumed. Of those assumptions, the most relevant were that:

- the delivery of design would be aligned with the Infraco construction delivery programme [ibid, page 0006, clause 3.4.2].

- the design delivery programme under the System Design Services (“SDS”) Agreement was the same as the programme contained in Schedule 15 to the Infraco contract [ibid, page 0006, clause 3.4.4].

- no additional earthworks would be required and the consortium would not encounter any below-ground obstructions, voids, contamination or soft material [ibid, pages 0006–0007, clause 3.4.11].

- the works required in relation to the road structures in Princes Street, Shandwick Place, Haymarket junction and St Andrew Square would not extend to full-depth reconstruction [ibid, page 0007, clause 3.4.12].

- the diversion of utilities would be complete in accordance with the programme, save for ones that had been specified in the Infraco contract as being the responsibility of the consortium [ibid, page 0008, clause 3.4.24].

21.6 I consider some of these assumptions further in paragraph 21.9 below, in the context of quantification of risk. For present purposes what is relevant is that, as was the position with elimination of risk, the strategy underlying the assumptions was of no effect because it was not implemented.

21.7 Turning to efforts to minimise and control the retained risk and to quantify it, the measures that were put into effect can conveniently be examined together. The first stage was to identify each risk and to consider the consequence for the Edinburgh Tram project (the “Tram project”) if it materialised. Initially, assessment of risk fell within the services that were to be provided by PB under the SDS contract but, following concerns about its performance, the matter was taken from it [Mr Bourke PHT00000022, pages 5–12; TRI00000110, pages 0039–0040, 0042–0043 and 0057–0058, paragraphs 41, 46 and 65 and ‘Brief on Proceedings of cost review’ – CEC01629344, page 0005]. It was considered that PB was not providing tie with the deliverables required under the contract. Initially, after the work was taken from PB it was carried out by Technical Support Services (“TSS”), which had originally been engaged to review the work done by PB. Once TSS assumed the primary role, the review function was provided within the tie team [PHT00000022, pages 12–13]. Later, Mr Hamill succeeded Mr Bourke and took on the primary role, with TSS returning to its reviewing role. Mr Bourke explained that the issues with the performance of the contract by PB meant that procurement of the Multi-Utilities Diversion Framework Agreement (“MUDFA”) works and the early stages of the Infraco procurement were carried out when risk management was not performing as intended [ibid, pages 15–17]. However, he was of the view that, by working together with TSS, tie was able to recover and that it did not affect the risks of controlling and managing procurement [ibid, pages 15–16].

21.8 Within tie, assessment of risk was carried out by a team that would consist of the person to whom the risk in question had been assigned, a cost manager (who would be a quantity surveyor) and the project manager, and they would seek to reach a consensus view on the risk issues [ibid, pages 27–28; Mr Hamill PHT00000023, pages 7–8]. In addition, on occasions when it was appropriate, the team might include a commercial manager and/or a planning manager. As is usual, the information resulting from these exercises was compiled into a risk register. This was initially carried out in a spreadsheet that was later held in specialist risk management software [PHT00000022, page 6]. Once the risks were identified, the manager for each risk would seek to identify mitigation measures that would reduce the likelihood of the risk occurring and/or limit the adverse consequences if it did. The measures, and the view as to their efficacy, were recorded in the risk register and were the subject of internal review [ibid, pages 22–24]. The contents of the register were reviewed over time, including whether further risks required to be added and whether the proposed mitigation was effective. The most important or critical risks were included in the primary risk register and were periodically presented to the Tram Project Board (“TPB”) [ibid, pages 31–33].

21.9 In order to quantify the risks that existed from time to time, a quantitative risk analysis (“QRA”) was undertaken. It is a standard method for evaluating the cumulative impact of risks [TRI00000110, page 0008, paragraph 9]. This requires that in relation to each risk an assessment is made of the residual risk after mitigation measures have been considered [PHT00000022, page 27]. A view was taken as to the percentage likelihood of each risk materialising and its minimum, maximum and most likely cost impact [Mr Hamill TRI00000042_C, pages 0004–0005; Mr McGarrity TRI00000059_C, page 0014]. This data was then processed in a Monte Carlo simulation – a recognised analysis technique in which the possible outcomes and their probabilities are assessed. As both the occurrence of the risk event and its consequences are inherently uncertain, it is necessary to take account of probabilities so that, rather than produce a single figure for risk, it provides a range of possible distribution of outcomes. It means that an assessment can be done to determine the likelihood of various outcomes. A probability can be selected and it will be possible to obtain a figure as to the risk allowance that should be made in order to have the desired degree of confidence that the budget will not be exceeded. If a selection is made that there should be only a 50 per cent probability that the budget is not exceeded, one allowance for risk will be indicated. However if, say, it is necessary to have a figure for which there is an 80 per cent confidence that it will not be exceeded, the allowance will be higher. As the degree of confidence sought rises, the increases in the allowance that must be made gets correspondingly greater as it is necessary to take account of risks which are remote but which might have large consequences if they occur [Professor Flyvbjerg PHT00000057, pages 3–4 and 8–15].

Risk in the FBC

21.10 Although, for reasons of commercial sensitivity, the precise figures were not published in the FBC, at the time it was issued, an allowance of just under £49 million was made for risk [CEC01423172; CEC01423173]. The FBC notes that the cost estimate included a risk allowance of 15 per cent [CEC01395434, Part 1, page 0017, paragraph 1.73 and Part 9, page 0178, paragraph 11.41]. This, and all the quantification up to that date, made the assessment on a P90 basis, which meant that there was a 90 per cent probability that the allowance would not be exceeded. This is more cautious than would be the case in most construction contract situations, where the probability required would not normally exceed 80 per cent. On that basis, it can be said that the allowance made in December 2007 was cautious. A report from the Office of Government Commerce (“OGC”) Readiness Review Team sent to City of Edinburgh Council (“CEC”) on 15 October 2007 endorsed the risk allowance that had been made, but appears to have conflated the issue with the availability of funding when it referred to “overall headroom” [CEC01496784, pages 0003–0004]. The FBC brought out a total cost of £498 million, including the allowance for risk, and noted that the available funding from both Transport Scotland and CEC was £545 million. The difference between these two sums – £47 million – was the “headroom” and it was distinct from and in addition to the risk allowance [CEC01395434, Part 1, page 0017, paragraph 1.73].

21.11 The risk allowance made at the time of the FBC (and all the allowances before it) assumed that the procurement strategy would be implemented such that design and utility diversions would be substantially completed prior to the award of the Infraco contract [Mr McGarrity TRI00000059_C, pages 0049–0050]. However, even the first version of the FBC [CEC01649235], published in October 2007,[31] noted that the assumption that the overall design work would be completed to detailed design stage when the Infraco contract was signed would no longer be true [CEC01649235, Part 5, page 0104, paragraph 7.53]. It also noted that MUDFA works would not be completed until winter 2008 but said that “potential conflicts between the utilities and infrastructure works will be minimised” [ibid, Part 5, page 0108, paragraph 7.77]. It is important to note, however, that this was on the basis that, at that time, the work was expected to be completed on cost and programme. Although this was not wholly unrealistic in December 2007, it was nonetheless an assumption but in the early months of 2008 it became increasingly obvious that it was unlikely to be true.

21.12 The completion of design works before the Infraco contract was let and the completion of MUDFA works before the infrastructure works got under way were both key parts of the procurement strategy that were intended to control or mitigate risk. As Mr McGarrity said, the intention was that all risks other than the costs of utility diversions or changes to design made by CEC post-contract award would be borne by the contractors [TRI00000059_C, page 0005]. Even at the stage of the initial draft of the FBC, it was apparent that these elements of the strategy would not be attained. In relation to completion of the design, Mr Bell noted that by autumn 2007 it was clear that the design would not be complete and that the bidders would not provide a fixed price by taking all the risk of change [PHT00000024, pages 140–141], and he accepted that there had been slippage in all versions of the design programme [ibid, pages 149–150]. As this meant that it was clear it would not be possible to adhere to the procurement strategy, this should have been disclosed clearly to CEC, together with an indication that it changed the project risk profile. It called for an examination of what level of risk would result. Consideration of whether there would be sufficient funding and whether the project represented a good use of public money (the Benefit to Cost Ratio) should also have been reviewed. Instead of this, it is apparent from the FBC that the principal focus and the main direction of energies was getting the project over the line to have contracts concluded on the basis of unverified assumptions that all would be well.

21.13 As was noted in Chapter 10 (Events between October and December 2007), even when the December draft of the FBC was issued – and therefore when the risk allowance was determined – there was still no finalised agreement with the infrastructure contractors as to the price for their works. Significantly, there was also no agreement as to how the issue of the incomplete design was to be addressed as between the parties and who would bear any additional costs arising from the completion of the designs. This led to the negotiations in Wiesbaden during December and the follow-up agreement also discussed in Chapter 10. As I note there, these agreements did not have the effect of transferring the risk of those additional costs. It is apparent, however, that this was not understood by anyone in tie at the time, and the view was that the agreement had removed the risk of design development from tie [Mr McGarrity TRI00000059_C, pages 0095–0096, answer 101 and page 0098, answer 104]. It is therefore not surprising that there was no specific mention or quantification of the additional risk at this stage. It is also not surprising that the suggestion from Mr Fraser that there be an additional contingency of £25 million to cater for changes between the preliminary designs and the final designs was not considered necessary and provoked Mr McGarrity’s comment “ALARM BELLS ALL OVER THE PLACE, WHAT ADDITIONAL £25 M???” [CEC01383999; CEC01384000]. This incident is mentioned in Chapter 13 (CEC: Events during 2006 and 2007) in the context of the report to CEC on 20 December 2007.

21.14 Mr Hamill was asked whether the risk that the contractual arrangements were effective should itself have been the subject of quantification for inclusion in the risk allowance, but he did not consider that the function of the risk allowance was to deal with the contracts not being sufficient to achieve the stated objective [TRI00000042_C, page 0019, answer 40]. This makes sense. It is apparent that the risk allowance is intended to address construction risks and not legal risks that, in any event, could not be assessed without input from legal advisers. The task of those advisers on risk management was to take steps to bring about a situation in which the risk was allocated as intended, rather than to quantify the possibility that the contract did not do as it was said to do. The failure at this stage to quantify the risk relating to the effectiveness of the contractual arrangements was part of the failures in relation to negotiation of the contract rather than any failure in risk management.

21.15 Within tie there was, understandably, a view that risk was managed in an appropriate way [Mr Bourke PHT00000022, pages 2–3; Mr Hamill PHT00000023, pages 2–3]. More significantly, although the OGC noted in its report of the review carried out in September and October 2007 that the actions of the TPB to respond to risks did not always reflect identified risks, it concluded that the processes for risk monitoring in tie were “impressive” [CEC01562064, page 0007, paragraph 10]. Professor Flyvbjerg was of the view that the work undertaken to understand risk was similar to that for other projects [TRI00000265, page 0027].[32]

21.16 Although these views address the procedures that were used to provide the risk allowance for the FBC, there was evidence of concerns in relation to the amount of the allowance that was made. In its review of the draft FBC, Transport Scotland had expressed a concern that the allowance of just 12 per cent for risk was too little, and it considered that the assessment should be made at P80 and P50 levels of confidence in addition to P90. The response from tie was that the figure had been derived from the QRA and had been agreed as appropriate in autumn 2006 by Transport Scotland advisers [CEC01631559, pages 0005 and 0007]. Professor Flyvbjerg considered that the estimate of risk was so low that it raised concerns about the quality of the work undertaken [TRI00000265, page 0025]. Although Mr Coyle expressed the view that the risk allowance did not seem adequate [TRI00000144_C, page 0013, paragraph 47] and Ms Andrew considered it to be low [TRI00000023_C, page 0012, paragraph 4, pages 0018–0019 and elsewhere], I am not inclined to place any weight on their concerns as they are highly subjective and are not supported by any analysis or evidence. However, it is apparent that, in some instances, the allowance made was wholly inadequate. The best example of this concerns the MUDFA works. In the budget at FBC in December 2007, the price for these was noted as being approximately £51.5 million and the risk allowance for them was just under £11.5 million. At financial close these figures were reduced to approximately £48.5 million and £8.5 million respectively.[CEC01423173]. At the time that he left the project, Mr McGarrity thought that the cost of utility diversions was about £70 million and work was continuing. After some reluctance to answer the question he agreed that the risk assessment made for utility diversions was inadequate; in fact, the cost overrun was approximately £50 million [Mr McGarrity PHT00000047, pages 123–126]. The reasons for the increase are considered in Chapter 8 (Utilities), but for present purposes the point is that even the application of a suitable process will not necessarily produce an accurate result.

21.17 Professor Flyvbjerg noted that although the method of analysis and the use of the Monte Carlo simulation give the impression of mathematical certainty, the information obtained from the exercise is only as good as the information put into it [PHT00000057, pages 32–33], and Ms Andrew made the same point [TRI00000023_C, page 0007, paragraph 4]. The inputs to the QRA are an exercise of judgement at the initial stage. The facts that a number of people provide input and that they are experienced should assist in obtaining accurate figures, but this is not always the case. Sometimes they may simply be wrong or have failed to anticipate a risk. More generally, the problem is that the initial determination of the values to be put on the individual risks and their consequences will be affected by optimism bias [PHT00000057, pages 5–6]. I consider this concept in more detail in paragraphs 21.54–21.97 below.

Changes in the risk allowance after FBC

21.18 Both in the choice of the P90 basis to assess risk and in relation to the process that had been undertaken to identify and quantify risks at the stage of the FBC, I do not consider that any criticism can be levelled at tie. Although some risks were understated, even in those instances I do not consider that this alone invites any criticism of the people involved and the issue is better addressed as one of recognising the fallibility of the analysis process, which I consider further below, in the context of optimism bias. However, although the way in which the allowance was derived at this stage was appropriate, the way in which it was handled between then and May 2008 is a cause for concern. There are three parts to this aspect which can be considered in turn.

(i) Reduction in risk allowance in February 2008

21.19 As a starting point, it is useful to have in mind why it might be desirable to reduce the risk allowance. Although it represents costs that may be incurred rather than those that it is planned will be incurred, the risk allowance is included as part of the overall anticipated cost of the project, and there must be funding available for the whole amount before the project proceeds. The intention is to avoid a situation in which the party paying for the works finds itself with a liability for which it does not have funds or, at least, does not have funds set aside. If the risk allowance increases, the estimate of cost will rise also and the requirement for funding will increase accordingly. On the other hand, if it was considered that risks had been reduced or eliminated such that the allowance could be reduced, the reduction in risk allowance could be set against any increases in the budget arising from other factors or the overall budget cost could be reduced.

21.20 It was always likely that some changes would be made to the allowance for risk between the FBC and signature of the contracts. Some of the risks that were included in the analysis were matters that might arise in the conclusion of the contracts. Once the contracts were in place, it could be said that that particular risk no longer existed and no allowance would have to be made for it. The “saving” that arises could be used to offset any additional cost arising as the contracts moved to conclusion. Moreover, negotiations prior to the conclusion of the contract might result in the transfer of risk from the client to the contractor, in which case there would be a transfer of funds from the risk allowance to the contract price [Mr Hamill PHT00000023, page 38]. A concrete example of this can be found in the fact that the additional costs arising from the Wiesbaden Agreement were met within the budget by a reduction in the risk allowance. The problem was not that this was done but that the risk had not in fact been transferred, so there was no justification for reduction of the risk allowance. As I considered in Chapter 10 (Events between October and December 2007), the written agreement in December 2007 that followed the Wiesbaden discussions did not transfer risk to Infraco. It should have been apparent from the correspondence from Infraco, which led to the agreement, that it did not intend to accept the risk. The problem lies not in the intention to exchange risk for an increase in price but in the fact that there was no transfer of risk, which was not appreciated.

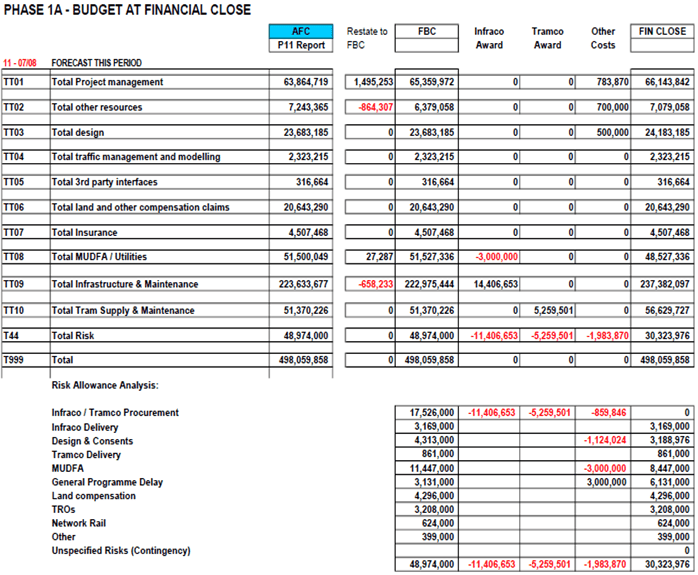

21.21 The first example of adjustment of the risk allowance after the FBC arose on 11 February 2008, when Mr McGarrity emailed Mr Hamill with a spreadsheet specifying modifications to the risk allowance [CEC01423172]. The attachment is reproduced in Table 21.1.

Table 21.1: Proposed modification to risk allowance in February 2008

Source: Phase 1A – Budget at Financial Close, CEC01423173.xls, Summary P11 [CEC01423173, Summary P11]

21.22 As was explained by Mr Hamill, the column headed “AFC” referred to the anticipated final cost at period 11; “FBC” referred to the Final Business Case; and the column headed “FIN CLOSE”, showed the anticipated position at financial close [PHT00000023, pages 46–48]. The smaller table to the lower part of Table 21.1 indicates in red the reductions that were proposed. It can be seen that between FBC and financial close:

(1) the cost increases, totalling approximately £21.65 million, were identified (rows beginning TT01 – £783,870; TT02 –

£700,000; TT03 – £500,000; TT09 – £14,406,653; and TT10 – £5,259,501) and the costs of MUDFA/Utilities (row beginning TT08) decreased by £3 million, giving rise to a net increase in costs (under these headings)

of £18.65 million;

(2) the total cost (the row beginning T999) does not change;

(3) between FBC and financial close the allowance to be made for risk is reduced from just under £49 million to £30.32 million; and

(4) the change is principally accounted for by reducing the Infraco/Tramco Procurement risk allowance to zero, with lesser reductions in the allowances for MUDFA and Design & Consents, and an increase of £3 million in the allowance for General Programme Delay. This had the effect that there was no increase in estimated costs despite the increase in sums that it was recognised would have to be paid to the contractors, and the end result was that the estimated costs for final close remained exactly the same as that in the FBC despite the Rutland Square Agreement.

21.23 The email from Mr McGarrity noted that the figures represented the latest negotiation with Bilfinger Berger Siemens (“BBS”) that had concluded the previous week but also noted that an update to the risk allocation was required, “based on risk allocation at Fin Close”. Mr Hamill’s reply of the same day [CEC01489953] was copied to Mr Bell and was in the following terms:

“The sheet which is titled ‘Summary P11’ contains information relating to the risk allowance which I am not aware of.

“You are more involved in the negotiations than me therefore I assume that where you have reduced the risk allowance you are content or have been assured that this is correct? I reviewed those risks which are included in the QRA on Friday and input will be required from others before we can amend these risks.

“I’ve attached the QRA with my comments and you’ll notice at the end a number of queries regarding potential ‘new risks’. Again, I would prefer someone to let me know if these issues need to be catered for in the risk allowance.

“Stewart, my main concerns here are that (a) we are reducing the risk allowance while the risk has not actually been transferred or closed and (b) the new risk allocation is not sufficient for the risks which tie will retain. I cannot overstate how anxious I am to ensure that the final QRA truly reflects the actual risk profile at financial close.

“Perhaps you have the information required to deal with the points raised above – if you want to meet to discuss then please let me know. I believe you, Steven and I (as a minimum) must fully understand what we are entering into at financial close.”

21.24 Mr Hamill accepted that he was very concerned when he sent this email [PHT00000023, page 40]. He felt that significant reductions had been made without any explanation or evidence [ibid, page 48]. As was noted in paragraph 21.20 above, he accepted that at contract award there can be situations in which risk is transferred to a contractor in return for an increase in the contract price, and that where this happens money will be transferred from the risk allowance to the price, but he said that he had sent his reply in these terms because, as risk manager, he was concerned that the risk allowance was being reduced in the absence of any justification. He said that he had no idea where the reductions had come from and he considered that the result was that the risk allowance did not reflect the risk profile [ibid, pages 40–41]. He stated that when he raised it with Mr McGarrity he became angry. Mr Hamill had also raised his concerns with Mr Gilbert but he was “frustrated” at being challenged.

21.25 Mr McGarrity said that the changes were agreed by senior members of the project team and reflected the reduction in risk as a result of the Wiesbaden and Rutland Square Agreements [TRI00000059_C, pages 0123–0124, paragraphs 32 and 35]. The Inquiry has not identified any written record of a meeting of the project team to make these changes. In view of the value of the change being made, I would have expected it to be the subject of formal consideration and that a record would be kept. In addition, it is not apparent how the changes could be said to be merited by the Wiesbaden and Rutland Square Agreements. The written agreement concluded following the discussions in Wiesbaden [CEC02085660, Parts 1–2]

primarily dealt with the contract price and recorded what was – or was not –

included within it. The Rutland Square Agreement [CEC01284179] increased the price and, among other things, put back the completion date, said that unforeseen risks would be shared 50/50, noted that the costs of changes arising from the newest version of the Employer’s Requirements was more than tie could afford, and set out the date by which the contracts were to be concluded. It is not apparent that either agreement could provide a justification for reductions to the risk in respect of either design or MUDFA. Although it is true that once the contract was in place it could be said that the risks of procurement could not arise, at that time the conclusion of the contract was still some time away and, until its terms were finalised, the risks of procurement were still live such that there was no justification for reducing the risk to zero. It appears that the real driver for the reduction was an attempt to present the price as being within budget despite the increase in price brought about by each agreement.

21.26 Mr McGarrity said that he did not recall any altercation with Mr Hamill when he raised his concerns in person and that he would have remembered it had it occurred [PHT00000047, pages 108–109]. Although, by implication, Mr McGarrity’s evidence might be construed as a denial of Mr Hamill’s version of events, it is also possible that with the passage of time he has forgotten the incident. In either case I accept the account given by Mr Hamill. If Mr McGarrity’s evidence is construed as a denial of the incident I prefer the evidence of Mr Hamill. Not only does it fit with the contemporaneous emails but I had the impression that he was truthful in his oral evidence about this matter and, indeed, was embarrassed by what had taken place. If Mr McGarrity has simply forgotten about the incident, that does not contradict the positive evidence given by Mr Hamill about it.

(ii) Manual changes to the QRA

21.27 Adjustments to risk continued even after the contracts had been signed. At the last minute before contract signature, both BBS and PB demanded additional payments. The demands were met in part, and the negotiations in relation to this are considered in paragraphs 11.125–11.130 of Chapter 11 (Contract Negotiations). This in turn gave rise to an issue as to how these increases in the price could be accommodated in the budget that had been approved. As I have noted in Chapter 12 (Contract Close), there was an increase in budget of £4 million at the last minute to accommodate them, and a statement as to why this was done was contained in the Financial Close Process and Record of Recent Events [CEC01338847]. The increase in the Infraco price was £4.8 million (four payments of £1.2 million). The view was that there was a reduction in exposure to risk of £4.6 million. Of this, £0.5 million arose from the capping of liability in respect of a risk already included in the QRA, and it was considered that a corresponding reduction could be made in the QRA figure. The paper recognised that, in relation to the other £4.1 million of “exposures” that were said to have been removed, the position was more “judgemental”. It considered that a sum equal to one-third of the aggregate value of the “risk improvement” that it had noted – or £1.3 million –

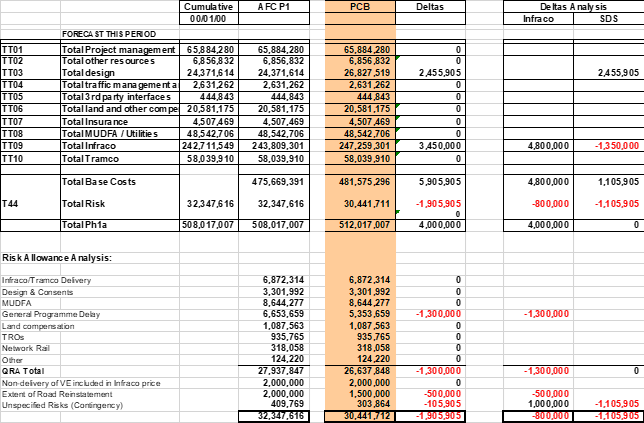

could be deducted from the risk allowance. Despite this, it is not immediately apparent that the matters identified could be considered to be removal of risks that had previously been valued in the QRA. At the same time it was recommended that an increase in risk allowance of £1 million should be made in order to provide a “cushion”. On 15 May 2008, the day after the contracts were signed, Mr Bissett emailed Mr Bell, Mr Hamill and others, saying that there was a need to “arrive at a final form [sic] settled base cost and risk contingency” [CEC01295328]. Four days later, on 19 May, Mr McGarrity sent a reply that referred to a meeting that had taken place that day, and attached a spreadsheet that, as he put it, “lays out a simple recon of how I think we get from the last reported estimate (£508m) to our final control budget (£512m)” [ibid]. The email stated that the risk allowance was to be reduced by £1.1 million “to fund the SDS increases”. The attachment [CEC01295329] is reproduced in Table 21.2.

Table 21.2: Proposed modification to risk allowance at Financial Close

PHASE 1A – BUDGET AT FINANCIAL CLOSE

21.28 The column headed “AFC” gives the assumed final costs that were in place prior to the last-minute demands. The column headed “PCB” provided the Project Control Budget. The increase of £4 million in the total costs for phase 1a from approximately £508 million to approximately £512 million is apparent. It is also apparent that the design cost has risen by £2.455 million and the Infraco costs by a net sum of £3.45 million, resulting in an aggregate increase of £5.905 million. This has been accommodated within the PCB of £512 million by reducing risk by £1.9 million in total (£800,000 in respect of Infraco and £1.1 million in respect of SDS). In relation to Infraco, the adjustments made in this table appear to be the same as those considered in paragraph 21.27 above. The net reduction in risk of £800,000 noted in the upper part of the table (Row T44) is the effect of reducing risk by £1.8 million (the £0.5 million and the £1.3 million) and then increasing it by £1 million. The reduction of £105,905 was not explained. The reduction of one-third of the assumed value of the “improvements” identified in the Financial Close Process and Record of Recent Events [CEC01338847] has been made entirely from General Programme Delay. This is hard to understand as, even on the basis of the description in that document, only one of them could be said to relate to programme delay, and that fact immediately casts doubt on the bona fides of the reduction. Nevertheless the changes proposed by Mr McGarrity reflected the recommendation by tie contained in that document.

21.29 In response to questions from me, Mr Hamill appeared to acknowledge that Mr McGarrity’s email was indicating an intention to use a reduction in the QRA figure to ensure that the project could be delivered within the agreed budget [PHT00000023, page 53]. Mr Hamill did not recall being provided with any information to justify such a reduction and was surprised that the change was being made. Despite the fact that the allocation of a risk was a live issue in the contract negotiations and those negotiations went on into April, Mr Bell and Mr McGarrity said that the QRA was not updated after 1 March 2008 [PHT00000025, pages 12–15; PHT00000047, page 36], so a revision to it could not be the justification for the change to the risk allowance. Mr Hamill was surprised that any change to the risk allowance was being made shortly after the contract was signed. His understanding was that the allowance of £32,347,616 for total risk in column AFC P1 in Table 21.2 was the risk allowance for the project [PHT00000023, page 56]. He replied to Mr McGarrity’s email forwarding a copy of the QRA and seeking a chance to discuss the changes [TIE00352326; TIE00352327]. In his oral evidence he explained that his concerns were that the way that the QRA was put together meant that it was not possible simply to change a single figure, that he was again being asked to make a change without there being evidence to justify it, and that the existing figures had been agreed with CEC and the change would “put us back to square 1” [PHT00000023, pages 56–59]. He said that he explained his concern to Mr McGarrity but in response he was told to make the change as it was what had been agreed [ibid, pages 60]. Whatever information was available to others about the reasons for the changes to the QRA it is apparent from the terms of his email that Mr Hamill was unaware of the justification for the changes and of any connection between these changes and the Financial Close Process and Record of Recent Events [CEC01338847]. As risk manager he ought to have been given evidence that satisfied him of the justification for the proposed change but as with the change in February, discussed in paragraphs 21.21 to 21.26 above, that was not done. He ought not to have made the changes in February and May 2008 until he was satisfied on the basis of evidence presented to him that there was justification for such changes. In making the changes to the QRA in May 2008 he sought to avoid the scrutiny of them by CEC officials.

21.30 Mr Hamill made the change as he had been directed. He sent an email to Mr McGarrity, Mr Bell and others on 27 May in the following terms:

“All,

“Please see attached spreadsheet which I have updated following our meeting last week. As agreed, Risk ID 343 which allows for delays has been reduced by £1300k which means we now have £5187k against this risk and, accordingly, the overall risk allocation has reduced by £1300k to £26637k.

“One thing which we all need to be aware of is that it is not possible to reduce the value of one risk in the QRA without affecting all the others. This is because the P80 allocation is driven by the total mean sum. Therefore, in order to get round this problem, I have basically ‘pockled’ the spreadsheet and hard-entered some values. This solves the problem and helps us get the final result past CEC as I doubt they will notice what I have done.

“I will revert to normal practise [sic] for future QRAs however in this instance I think this is the best way to do it in order to avoid unnecessary scrutiny from our ‘colleagues’ at CEC.

“Please confirm you are content with this approach or otherwise by close of play Friday 30th May. I will take no response as acceptance.” [CEC01288043]

21.31 He explained in his evidence that a change to one cell would have affected the remainder, so he had replaced the formulas on some cells with fixed numbers and reduced the entry for Risk 343 [PHT00000023, pages 61–62]. I questioned him on his use of the word “pockled”, which implies minor dishonesty. He said that there were two elements to this: the reduction in risk, and the way in which it was achieved [ibid, page 63]. He said that as far as the decision to reduce risk was concerned, he had been told that there had been a transfer of risk in the contracts as they were concluded. He did not consider that the explanation that he had been given was satisfactory, but as it came from his superiors it was an answer that he had to accept [ibid, page 64]. The second element was how the change was to be represented, and this was a switch to manual entries as the changes could not be accommodated within a QRA. It is clear that this was a way to effect the reduction that he had been instructed to make. The extent of the changes to cell entries is apparent by comparing the original Excel files for the spreadsheet containing the QRA from February 2007 [CEC01489954] to the one attached to his email [CEC01288044]. In the more recent one, all the entries for “P80 Risk Allocation” are fixed numbers rather than the formulae in the earlier version. This is not readily apparent on an examination of the printout or the pdf version.

21.32 It is revealing that in the email Mr Hamill said that the purpose of the change he had made was to “get the final result past CEC” [CEC01288043] and that he used inverted commas when describing the CEC employees as colleagues. He said that this reflected the atmosphere and mood between tie and CEC and that they were not aligned [PHT00000023, page 62]. This was indicative of a poor working relationship in which CEC officials were viewed as adversaries rather than as representatives of the entity for which tie was providing a service. More fundamentally, it indicates an intention that CEC should not be aware of what had been done. This issue and the working relationship between CEC and tie are considered further in Chapter 13 (CEC: Events during 2006 and 2007), Chapter 14 (CEC: January–May 2008), and Chapter 18 (CEC: May 2008 –2010).

21.33 Mr McGarrity denied that he told Mr Hamill just to get on with it and make the change [PHT00000047, page 77], but I accept Mr Hamill’s account as being consistent with the contemporaneous documents and the other events I have referred to. Mr McGarrity said that the email was “unfortunate” [ibid, page 76] and said he would not have “pockled” anything. He was not concerned at the manual adjustment and did not worry about the whole QRA not being re-run. He considered that the language used in Mr Hamill’s email should not have been used and accepted that it suggested deception. In response to a question from me about whether he had an obligation to deal with the matter in view of the suggestion of deception, he merely stated that he had no recollection of having had a concern about the language used “given the materiality of the amounts involved” [ibid, page 78]. As to the means by which the change was made, he said:

“I would have been happy with a manual adjustment to the QRA, but also I would have wanted to make sure that Council officers knew that that’s exactly what had been done.” [ibid, page 76.]

21.34 Despite this, Mr Hamill sent the altered spreadsheet to Mr Coyle of CEC, attached to an email of 11 June 2008 [TIE00352465], and no mention was made of what had been done. Mr McGarrity’s suggestion that perhaps the matter had been discussed with Mr Coyle was, as he himself recognised, clutching at straws [PHT00000047, page 83]. When I asked him later whether he had drawn what had been done to the attention of the CEC Director of Finance, he said “I don’t remember having any specific discussions with my finance colleagues about this item” [ibid, page 78]. I did not consider that Mr McGarrity was giving truthful evidence about this incident. He was clearly aware of the significance of the language used in Mr Hamill’s email but sought to distance himself from any suggestion of his awareness of the deception played upon CEC officials. He claimed that he did not remember whether he had discussions with officials in CEC’s Department of Finance when it was patently obvious, from his demeanour and from the surrounding circumstances, that he had not. He speculated about the possibility of Mr Hamill having explained to Mr Coyle what had been done, although it was apparent that no such discussion occurred or was likely to have occurred in view of Mr Hamill’s reference to unnecessary scrutiny by officials in CEC.

21.35 Mr McGarrity was not the only one who was aware of what was happening and was content with it. Mr Bell stated that the

“intent was clearly to make that adjustment identified against delay so that was traceable, not to mislead anybody in relation to QRA”

[PHT00000025, pages 24].

but this is entirely at odds with the statement in Mr Hamill’s email that his action “helps us get the final result past CEC as I doubt they will notice what I have done” [CEC01288043]. The intention was quite the opposite of what Mr Bell claimed. As to the means by which the change was made, Mr Bell’s suggestions that it was a “transparent adjustment” [PHT00000025, page 27] and there was “no subterfuge” [ibid, page 90] are wholly unsupported by the evidence and I have no hesitation in rejecting them.

21.36 Mr Bell attempted to justify the reduction in the sum allowed for general delay by suggesting that the four payments of £1.2 million each, which it had been agreed in the Kingdom Agreement would be paid to BSC to meet its late demands, were an incentive that would reduce general programme delay [ibid, pages 85–88]. I doubt that this view could genuinely have been held by him; it certainly does not stand up to any scrutiny. The payments are not linked to reaching milestones by a particular date and therefore provide no incentive for early completion. Mr McGarrity even recognised that the payments did not manage risk at all, as they would be made irrespective of when the milestones were reached [PHT00000047, page 70]. To suggest that this would reduce delay with the result that risk allowance could be reduced appears to be an attempt to justify the reduction in risk allowance that had to be made to control the effect of the later concession. I therefore reject this proffered explanation.

21.37 Although the effect of the change may not have been material in the context of the project as a whole, the concern is not just that the change was made and the QRA was not rerun; it was that the representations to CEC were that the figures were the result of the QRA exercise that had been ongoing for some time when they were not [see “Close Report” CEC01338853, page 0028]. Mr McGarrity’s approach discloses an acceptance that statements that were untrue could be made to CEC if they were what it took to get the project under way. Although the sum may not have been material, the existence of this attitude within tie is highly material. Mr McGarrity accepted that, as the client, the Council needed to be properly informed [PHT00000047, page 80], and I do not see how he can reconcile that with his views that what Mr Hamill said was happening, was not material. This is particularly true in light of the fact that he recognised that there was scope for conflict of interest arising out of the desire within tie to lower the overall budget. It is manifest that the intention was one of concealment and that the recipients of Mr Hamill’s email were aware of this. I consider this in Chapters 14 and 18 relating to events between January 2008 and 2010 from CEC’s perspective.

(iii) Change to basis of assessment

21.38 Until February 2007, the QRA had been calculated to a P90 probability [CEC01489954] – in other words, as explained in paragraph 21.10 above, there was a 90 per cent probability that the additional cost would not exceed the output from the model. On the other hand, even before the manual changes mentioned in the immediately preceding section, the QRA in the spreadsheet attached to Mr Hamill’s email was expressed to a P80 probability, which means that there was only an 80 per cent probability that the costs would not be exceeded. Where the probability threshold is reduced, the allowance that must be made for risk is reduced, which in turn reduces the overall budget cost. Despite this, nothing was said to draw attention to the change that had been made, to explain the effect that it would have had on the total risk allowance or to justify it.

21.39 Mr Hamill said that he could not recall the reason for the change, but he did not think that it was unusual to quantify risk as a P80 level of confidence rather than P90 [PHT00000023, pages 57–58]. That view was supported by Professor Flyvbjerg and the OGC. Transport Scotland had expressed the view that figures should have been given for the P50 and P80 levels. If, at the outset, the assessment had been carried out at a P80 level there could have been no complaint. The concern is that a change was being made at a late stage after CEC had given approval, that there does not appear to be a proper basis for it, and that it was not made in a transparent manner.

21.40 The issue of which probability level should be used had been raised earlier in 2008, in an email from Mr Hamill to Mr McGarrity on 28 February 2008 [TIE00351419]. This email shows the difference that is made by adopting the different degrees of confidence. At the P90 level, risk for phase 1a was £31 million, whereas at the P80 level the risk was £28 million. In this email, Mr Hamill observed that changing to P80 would require tie to convince CEC that the lower confidence level was satisfactory, but he thought that CEC “would be uncomfortable about essentially becoming 10 per cent less confident about delivering to budget”. Although he recognised that a figure of P80 from the outset of a project would be accepted by most people, he considered that a change from P90 to P80 at that stage would be hard to justify. The email said that that the only justification would be if tie was so confident that it had secured a fixed-price deal that minimised risk to the extent that the extra allowance was not required. In his oral evidence, however, he acknowledged that, at the date of his email, negotiations were ongoing and it would not have been possible to rely on that justification [PHT00000023, pages 69–70]. The email continued:

“I fully appreciate the need to reduce costs where possible in order to get the deal done however, given that we have reduced the figure by a considerable amount so far, I recommend manipulating the current information to an acceptable P90 figure rather than go through the hassle of trying to persuade CEC of the ‘benefits’ of a P80 figure.” [TIE00351419]

21.41 He explained that his reference to “manipulating” the information was referring to the fact that, as noted above, changes had already been made on 11 February and that there should not also be changes to the confidence level. Despite this, it is clear that the change in the confidence level from P90 to P80 was made in the Risk Allocation Report for the period ending 1 March 2008 [TIE00352327].

21.42 Mr McGarrity said that although the change from P90 to P80 was an idea that appeared to have originated within tie, he could not remember why the change came about. He said it would not have been done simply in order to be able to reduce the budget estimate but he could not think of any other reason why it would have been done [PHT00000047, pages 41–47]. He accepted that there was a collective responsibility within tie for it [ibid, page 48]. He said that it would not have happened without CEC officials being aware but could not recall having told them [ibid, page 43; TRI00000059_C, page 0129, paragraph 46]. I agree with Mr Hamill’s assessment at the time, mentioned in paragraph 21.40 above, that tie would need to convince CEC officials that the lower confidence level about delivering the project within budget was acceptable. In light of the importance of this issue to CEC I also agree with his assessment that they would be uncomfortable with such a change and would take a lot of persuasion that it should be made. In that situation the mere inclusion of P80 on spreadsheets issued by tie to CEC after March 2008 was not adequate. These spreadsheets were similar to earlier ones in which the calculations had been based upon P90. Before any decision was taken to make the change, I would have expected to see documentary evidence such as emails or minutes of meetings recording discussions with CEC officials about the proposed change and the outcome of that debate. I do not accept Mr McGarrity’s assurance that CEC officials were told about this change. There is no written record of the change and its effect being drawn to their attention and, as I note at paragraph 21.37 above, in other respects, there was a desire to conceal matters from CEC. It would have been the natural thing to have included mention of it in the Close Report, but that was not done. Had the information been provided, it would have been appropriate and necessary that it be in writing and that a written response was obtained acknowledging the change and its effect. Mr McGarrity’s bland assertion that there was no manipulation [TRI00000059_C, page 0129, paragraph 48] cannot sit with the facts.

21.43 Mr McGarrity pointed out that the changes that were made were not all reductions to the risk allowance, that at times new risks were added to the risk register, that risks for delay and consents and approvals were augmented and that a figure of £2 million was added for road improvements [PHT00000047, page 59]. As I noted in paragraph 21.29 above, the last run of the QRA was at the start of March, but it is correct to say that some new risks were added. However, in my view this does little to mitigate the use of risk allowance as a means to ensure that the costs estimate “fits” within the budget figure previously identified. The sums in question are not material when compared with the cost overrun of the project as a whole. The concern is that they demonstrate an attitude – in relation to both communication with CEC and whether it was prudent to proceed – which, in my view, did make a material contribution to the cost overrun.

Representation of risk at contract close

21.44 In paragraph 21.13 above, I express the view that it was not surprising that no allowance was made at the stage of the FBC for the costs arising from the difference between the preliminary designs on which the prices had first been given and the final design because the tie personnel did not appreciate that the risk had not been passed to BSC. By the time of contract signature, after more than four months of negotiations, the position was different. By then it was known that it had not been done, or at the very least that there was a material possibility that it had not been done. Despite this, Mr McGarrity said that, at contract signature, the view was that the only risks arising from design that would be borne by tie were those arising from getting consents and approvals [TRI00000059_C, page 0126, paragraph 40]. He said that he asked within tie what development of design might occur from the preliminary designs that would be at tie’s risk in terms of the Wiesbaden Agreement, but he was not told of anything [PHT00000047, pages 152–153]. He thought that the risk had been transferred and consciously decided that no further provision was required. The view that he took, however, is entirely unjustified in view of what had taken place in the negotiations of SP4. BSC had made it clear that it would not accept the risk of design development and SP4 contained an express acknowledgement that not all the pricing assumptions held true even at the date of contract signature. Mr Bell confirmed that he was aware that significant change in design was at tie’s risk and was aware that after contract signature there would be Notified Departures [PHT00000025, pages 60–65]. I am not in a position to assess whether Mr McGarrity made the request of his colleagues that he says he did and, if so, why he was not made aware of the problems, but the number of persons involved in negotiation of the contract meant that the appreciation of the risk was sufficiently widespread that it should have been picked up. On any view, however, within tie there had been a debate about the issue as the decision had been made to press ahead with the conclusion of the contract and to fight claims “tooth and nail”. It is quite clear that there was an awareness of risk.

21.45 By the time of contract signature, it should have been apparent that the issues with the design were not the only factor that might lead to additional cost. Pricing Assumption 24 was to the effect that utility works would be completed in accordance with the programme, apart from utility diversions to be undertaken by Infraco as part of the provisional sums included within the Infraco works and specified in Appendix B [USB00000032, page 0008], yet it was apparent from various reports in the two months before signature that progress with the diversion of utilities was behind programme. The Project Director’s report to the meeting of the TPB on 12 March 2008 noted that at that date progress was three weeks behind programme [CEC01246825, page 0013]. His report to the TPB meeting on 9 April 2008 noted that there had been no recovery of the previously reported slippage and that cumulatively there was a delay of approximately six weeks [CEC00114831, Part 1, page 0013]. The presentation for the meeting of the TPB on 7 May 2008 also noted that there was further slippage in the programme and that the delay to the critical path remained at two weeks [CEC01282186, page 0015]. Even at this stage, it should have been apparent that this would generate a Notified Departure and that the ability of BSC to carry out works would be affected. Despite this, it was clear from the evidence of Mr McGarrity that although a general allowance had been made for delay, there was no distinct allowance for delay caused to the Infraco works as a result of MUDFA delay [PHT00000049, page 79]. It appears from the various progress reports on the MUDFA works that the delay was attributable to several reasons, including the discovery of unexpected obstructions and a larger number of utilities in terms of lineage and chambers than anticipated. In that situation one might have expected tie to identify the risk of that occurring on other sections of the route, as ultimately occurred, and to have assessed and allowed for consequent delay to the Infraco works.

21.46 Mr Bell said that tie was not in a position to calculate how many Notified Departures there were likely to be and what the total value would be [PHT00000024, pages 117–119]. I find that surprising when regard is had to the work that was done to consider risk generally. It cannot be reconciled with other evidence that Mr Bell gave. He said that estimates had been made of the exposure to risk where it was considered that there was a danger that a pricing assumption would not hold, with the result that there would be a Notified Departure [ibid, pages 110–112]. When he was asked whether he had reviewed the risk allowance with reference to the assumptions in SP4 he answered:

“I reviewed the Pricing Assumptions and the items I considered were – had the potential to have a Notified Departure impact, and satisfied myself that I considered the total risk allowance was adequate.” [PHT00000025, page 0005.]

21.47 He said that he did this early in May [ibid] but, as I note in paragraph 21.29 above, the QRA was not run after 1 March 2008. If Mr Bell did a review it must mean that it did not identify a single requirement for a change, and I cannot see how that was a realistic possibility on the known position. Even if it was the case that tie could not calculate the total value of Notified Departures, clear notice of that fact should have been given to CEC.

21.48 Mr Bell said that the expectation that pricing assumptions would fall was disclosed by the letter of advice from DLA Piper Scotland LLP (“DLA”) [CEC01033532]. I do not agree with this view of the letter. Under the heading “RISK”, it stated:

“Following on from our letter of 12 March, we would observe that delay caused by SDS design production and CEC consenting process has resulted in BBS requiring contractual protection and a set of assumptions surrounding programme and pricing.

“tie are prepared for the BBS request for an immediate contractual variation to accommodate a new construction programme needed as a consequence of the SDS Consents Programme which will eventuate, as well as for the management of contractual Notified Departures when (and if) any of the programme related pricing assumptions fall.” [ibid, page 0003.]

21.49 It was noted in questioning of Mr Bell by Counsel for DLA that, within the Risk Allocation Matrix referred to in the letter, it was recorded that the definition of “Compensation Event” included execution of utilities works or MUDFA works [PHT00000025, pages 67–72; CEC01347795, page 0022]. In terms of the Infraco contract, a compensation event could give rise to a liability for additional payment. In that questioning it was also noted that, in the text quoted above, there is reference to “Notified Departures” in the plural. Nonetheless, the issue is whether, taken as a whole, the letter gives notice of the risks that were known at the time. My view is that it clearly does not. Whatever may have been in the minds of Mr Fitchie and/or Mr Bell, it is clear to me that the intended readers of the letter would have no idea of the scope of the exposure to risk that was being undertaken as a result of the failure to adhere to the procurement strategy.

21.50 In a consideration of the evaluation of risk it is appropriate to emphasise that it is a process that seeks to put an identified value on something that is inherently uncertain. It is necessary also to have in mind the meaning of the confidence thresholds. If the budget makes an allowance for risk calculated at 50 per cent probability, it means that there is as much chance that the final cost will exceed the budget figure as there is that it will come within the budget [Professor Flyvbjerg, PHT00000057, page 9]. Even if the probability is increased to 80 per cent, it means that there is a one-in-five chance that the budget cost will be exceeded. Whichever degree of probability is selected, it considers only the chance that the figure will be exceeded and provides no information at all as to the extent by which the budget figure may be exceeded [ibid, page 10]. It appears to me that there was a lack of understanding of the position when decisions were taken by CEC in relation to the project. The confidence level chosen for the Tram project, when read with the references to a fixed-price contract, could easily give an impression that this was a figure that would not be exceeded. That was never the case with the Tram project: there was always a recognised chance that the budget would be exceeded although, in giving the go-ahead, the Councillors may not have been aware of this.

21.51 I have indicated above where I consider that the presentation and management of risk were not appropriate. The issue arises as to whether the outcome would have been any different had the matters that I note not taken place. In that situation the estimate of risk would still not have been anything like sufficient to accommodate the cost overrun that occurred. Nonetheless, if there had been an appreciation of the increased risk that was being accepted by CEC it could have made some difference. For instance, it might have been the case that additional controls and checks were put in place to evaluate the contractual position. A decision might have been taken to revisit the contract and accept a higher initial price in return for a different balance of risk. The scope of the project might have been restricted. These are only possibilities and, clearly, it is speculation to imagine what might have been done with full knowledge. However, there would at least have been an opportunity to take action and to make decisions that were fully informed. That is part of the function of assessment of risk, and what was done by tie failed in this objective.

21.52 Another consequence that arises from the appreciation that risk assessments always contain the possibility of an overrun is that some consideration should be given to the ability of the party undertaking the project to meet that additional cost. Professor Flyvbjerg noted that a body that undertakes a portfolio of large projects is likely to be better able to tolerate the risk than one that undertakes only one large project. This is because there is a larger overall budget within which to contain the overrun, because there will be more experience of managing such projects and because the organisation will have the necessary skills and expertise to deliver the project [ibid, page 20]. This reinforces the view that I express in Chapter 22 (Governance) that there were pitfalls in having the project conducted by a single-purpose vehicle company with no prior experience of delivering similar projects. When one is considering the funding of certain major public-sector projects from the public purse, including where that funding is provided by a local authority, there may be advantages in including them within the portfolio of projects undertaken by the Scottish Ministers even although they are wholly within the geographical boundaries of a single local authority. Reaching a concluded view on this is beyond the scope of this Inquiry but it is an issue that it would be of benefit to have explored by a working group consisting of representatives of the Scottish Government and the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities in the interests of protecting the public purse and maximising the benefits from public expenditure on major projects.

21.53 It may be commented that the Inquiry has focused on the matters that went “wrong” for tie and does not consider all the risks that did not arise, which were mitigated successfully or which were accurately quantified. This is correct, but it is necessary to take this approach. The purpose of assessment and quantification of risk is to control the costs. When that is the objective, it does not matter if 99 per cent of the risks are controlled if the 1 per cent remaining leads to a huge escalation in costs. If that occurs it can be said that overall the process has failed. When considering the reasons for the increase in costs, it is the risks that were not identified, controlled and priced that have to be considered.

Optimism bias

21.54 The Inquiry heard evidence and had a report from Professor Flyvbjerg. He is BT Professor and inaugural Chair of Major Programme Management at the Said Business School, Oxford University, and a Professorial Fellow of St Anne’s College, Oxford. He is a leading author on the subject of optimism bias. In his report, he described optimism bias as follows:

“a cognitive predisposition found with most people to judge future events in a more positive light than is warranted by actual experience. Clearly an optimistic budget is a low budget, and cost overrun follows.” [TRI00000265, page 0006.]

21.55 As this description indicates, it is a concept that originated in the field of psychology, in the works of Professor Kahneman, but over the years has come to be applied in many sectors including major construction projects.

21.56 I have noted at 21.9 above the process that is undertaken to produce a QRA. This consists of judgements being exercised by a team of people. Professor Flyvbjerg noted that the fact that a number of people are involved in the exercise gives a broader view of what the risks might be. However, the major problem with it is that it relies on the subjective evaluation by team members. That means that the outcome will be distorted by optimism bias, resulting in an underestimate of the negative aspects of the project, such as the cost and risks, and an overestimate of its positive aspects, such as the benefits and opportunities. Optimism bias affects the identification of risks, the evaluation of their probabilities and consequences and the effectiveness of measures taken to mitigate them [PHT00000057, pages 5–7 and 25–27].

21.57 The bias is addressed in projects by recognising that the estimates as to how much a project will cost and how long it will take are likely to be understated. Therefore, for the purposes of budget planning and assessing whether a project is worthwhile or which project should be allocated finite resources, an allowance is made for the extent to which the bias is likely to have distorted the prediction of the outcome. Allowances for risk are built up internally by means of persons engaged on the project considering where risks arise, how likely they are to materialise, what their consequences might be and how they can be mitigated. As the people within the project will be affected by the bias it is necessary that the allowance be determined by a process using external data. The one that is used is known as reference class forecasting. In this method, the likely overrun is determined by looking at the average overrun that has occurred in a series of projects (the reference class) of a similar nature. The rationale for this is that consideration of what has actually transpired in past projects is a more accurate predictor than attempting to anticipate what will happen in future in the project in question. As Professor Flyvbjerg put it:

“the assumption is that the best estimate you can get is what already happened to previous projects historically, and you can’t better that by thinking that you are clever enough to figure out what is actually going to happen to this specific project that you are looking at.

“You will not be better at predicting the future than the historical data for the project [sic] that have already happened. That’s the – that’s – a body of research that has been done that has proven that, and that is therefore – that is the result that you take into this methodology.” [ibid, pages 27–28.]

21.58 By using the reference class the intention is that subjective judgement with its inherent bias is removed or at least reduced.

21.59 The adherence to the reference class need not be slavish as account can be taken of circumstances in individual projects, but Professor Flyvbjerg was at pains to emphasise that any adjustment must be based on empirical data rather than judgement if reintroduction of the bias is to be avoided. He cited, as an example of where an adjustment might be made, a situation in which the team responsible for delivering the project has a documented record of achieving results better than the average over a period of time, although he had not come across a situation in which ultimately it was found that an adjustment was justified. Although evidence of a documented record of a project team being consistently better than average might justify adjustment of the average ascertained from a review of the reference class, mere belief that the team was good or had a novel approach to procurement that would avoid the problems would not suffice [ibid, pages 45–46].

21.60 Professor Flyvbjerg considered that it remained appropriate to undertake a conventional QRA with a risk register identifying and quantifying risk and seeking to reduce it. These are all relevant to the day-to-day management of the project and provide a useful overview, but it is necessary to adjust the conventional QRA by applying an optimism bias uplift based upon empirical data from the reference class [ibid, pages 31–32].

21.61 If an allowance is made for optimism bias the estimated cost of the project is increased, and that might be considered unattractive by promoters of the project when arguing for its viability and seeking to attract finite funding resources. Professor Flyvbjerg explained that it could nonetheless have a beneficial effect on the outcome of the project. As he put it:

“if you don’t stay within budget, you have political scandal, you’ll be on the front page of the media, and all of a sudden the project team that is supposed to deliver the project will be preoccupied by putting out fires in the media, and applying for more funding or raising more funding for the project, because they don’t have enough money now evidently because there’s an overrun. And that will distract them from what they are supposed to do, which is deliver the project, and the quality of delivery would therefore suffer, which in itself will affect the cost and we see this vicious cycle happening with projects once that starts. So it actually may affect the outcome of the project in that way.” [ibid, pages 12–13.]

21.62 It is apparent that several of the consequences of likely overspend that he identified existed in the Tram project.

21.63 In common with the allowance for risk, Professor Flyvbjerg recognised that there is a danger that if an allowance is made for optimism bias, the costs will rise to use it. As he put it, “if the money is there, it’s going to be spent” [ibid, pages 15 and 100]. He considered that measures could be put in place to avoid it, and one possibility is to make it difficult to draw down on the contingency funds. He said that this is done by the UK Government for its major projects [ibid, page 17]. He said, however, that the most efficient way of avoiding use of the allowance is to have a contract structure that provides incentives to a contractor not to go over budget [ibid, pages 15–16]. This might take the form of incentives payable to the contractor if it completes the work below budget or on budget, as well as a requirement that the contractor and the employer share the cost of any expenditure in excess of the budget. Several standard forms of contract provide such an incentivised structure. They are not always popular in the public sector, where the view can be taken that if the project can be done for less money it should be done that way and the contractor should not be entitled to additional payment for achieving this. In my view resistance to an incentivised structure that shares savings and increased expenditure between the contractor and employer is unrealistic and short-sighted.

21.64 Because such contracts contain terms that recognise that the price may change, they are often considered not to be fixed price. However, Professor Flyvbjerg considered that what may be termed a fixed-price contract means that the contactor lacks any incentive to reduce costs [ibid, page 18]. Instead where issues arise under the contract there is an incentive on the contractor to pass the blame to the employers to avoid penalties being imposed or to make additional claims and this generates conflict. As he put it:

“I would actually say in general, in the vast majority of cases, the notion of a fixed price contract is a theory. It’s an illusion that doesn’t materialise in reality.

“It’s called a fixed price contract, but it never ends up being fixed price or almost never ends up being fixed price. There are variations, and other things that happen on big and complex projects like what we are talking about. It’s impossible to predict everything that can happen, and therefore everything is not in the contract.

“So situations will arise where things happen where it becomes an open question. Who is going to pay for this? And a builder will say: it’s not us; and maybe the owner will say: it’s not us; and then you have a conflict, and often arbitration or even going to court.” [ibid, page 19.]

21.65 A false confidence in a “fixed price” and the inevitable increase in cost which follows seem to me to encapsulate what happened with the Tram project. If this situation is to be avoided, it is necessary either to have contracts in which there is no scope for any additional payments or to move away from the desire for a fixed price and have an arrangement where all parties share a common interest in keeping the cost down. Contracts of both types have been used in Scotland for civil engineering projects. The pursuit of the chimera of a “fixed price” contract was attractive in political terms to get the project approved but planted the seeds of the problems that were to grow to bedevil the project.

Government guidance on optimism bias

21.66 A number of Government publications have given guidance on the application of optimism bias in contracts:

- Mott MacDonald’s Review of Large Public Procurement in the UK, carried out for HM Treasury in July 2002 [CEC02084689]

- HM Treasury’s 2003 Green Book [CEC02084256, Parts 1–2]

- Supplementary Green Book Guidance [CEC02084818]

- the Department for Transport’s June 2004 Guidance on “Procedures for Dealing with Optimism Bias in Transport Planning” [CEC02084257]

- the Scottish Transport Appraisal Guidance (“STAG”) issued by the Scottish Ministers in 2003 (updated 2005) [CEC02084489]

- the Department for Transport’s, Transport Analysis Guidance on “The Estimation and Treatment of Scheme Costs” issued in September 2006 [CEC02084255]

21.67 It is not necessary to examine the content of each of these in great detail but it is useful to look at some of the main issues that arise to assist in evaluating what was done by tie and to set out the basis for my recommendations in this regard.

Mott MacDonald’s Review (2002)