Chapter 22: Governance

Project-specific governance structures

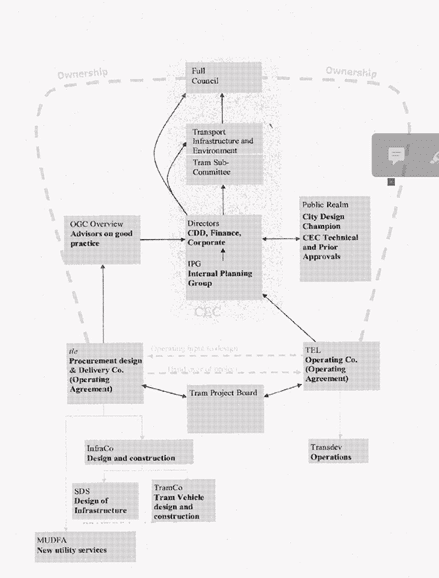

22.1 The governance structures put in place for the Edinburgh Tram project (“the Tram project”) from time to time were complicated and confusing. Perhaps unsurprisingly, at times they were not adhered to. This means that it is not possible to give a concise and comprehensive statement of what was intended and what was in fact done. I have, however, attempted to identify the principal bodies involved and applicable guidance, and have prepared a timeline summary as to how matters developed. Identifying these makes it possible to evaluate what was done. There were two principal bodies – Transport Initiatives Edinburgh Limited (“tie“) and Transport Edinburgh Limited (“TEL”) – and I turn to consider them first.

Transport Initiatives Edinburgh Limited

22.2 On 18 October 2001, the City of Edinburgh Council (“CEC”) resolved in principle to set up an “arm’s-length company” to develop and deliver the New Transport Initiative [USB00000228]. It would be regulated by the memorandum and articles of association and a shareholders’ agreement. Individuals from the private sector were to be approached to join the board of the company, which would also comprise: councillors, including those from Opposition parties; the Executive Member for Transport; and the Executive Member for Finance. It was established by May 2002 under the name “Transport Initiatives Edinburgh Limited”. Its name was changed to tie Limited on 24 August 2004 and to CEC Recovery Limited on 13 May 2013. It is referred to in this Report generally as “tie“. It is important to note that this company was established with a view to its being the body to implement the whole of CEC’s New Transport Initiative. This included a proposal to instruct a road charging scheme, together with a programme of transport improvements including improvements to the bus network, improvements to the rail network, a ring of “park and ride” schemes and a network of pedestrian routes [USB00000228, pages 0011 and 0033–0034]. The Tram project was just one of those improvements.

22.3 In common with other local authorities, CEC already had experience of undertaking activities through companies wholly or principally owned by it [Dame Sue Bruce PHT00000054, page 5]. These examples included Lothian Buses (“LB”), the Edinburgh International Conference Centre, Edinburgh Leisure and companies engaged in property development. The list of the major companies at that time appears in Appendix 2 to the report prepared by the Chief Executive of CEC, dated 13 December 2001 for the Council meeting on 18 December [CEC02084490]. However, the ambiguity as to the precise meaning of the expression “arm’s-length company” and the consequences that it had for the management of the project provide the basis for many of the difficulties in management that were to follow. I consider these difficulties below.

22.4 It was anticipated that an operating agreement would be concluded between the company and CEC to regulate its activities [USB00000232, Parts 1–6]. An unsigned draft of the operating agreement concluded between tie and CEC in 2002 [CEC02086416] stated that the services to be provided were to develop, procure and implement integrated transport projects that were part of the Integrated Transport Initiative. This 2002 agreement was superseded by a further version in September 2005 (the “2005 Agreement”) [CEC00478603]. This extended the company’s services to include third-party projects in the South East of Scotland Transport Partnership area approved by CEC. Again, it was not specific to trams.

22.5 The later agreement made provision for the appointment by CEC of a monitoring officer in relation to the company. Such an appointment was in accord with CEC policy to monitor the company to ensure that CEC’s interests were safeguarded. The detailed obligations of the monitoring officer are set out in Appendix 1 section C to the Chief Executive’s report entitled “A Framework for the Governance of Council Companies”, approved by CEC in December 2001 [CEC02084490]. All new and existing companies were required to adopt the code. Included in his obligations was the duty to ensure that the company adhered to best practice at all times, particularly in relation to corporate governance, to achieve its objectives. The appointment of a monitoring officer was clearly intended to oversee the company’s activities and governance to safeguard CEC’s interests. The company monitoring officer is distinct from the Tram Monitoring Officer (“TMO”), whose role I consider below.

Transport Edinburgh Limited

22.6 The first major addition to the governance structure was TEL, which was established in summer 2004 [CEC01875550] to enable integration of bus and tram services in a single entity and to promote transport policy generally [Mr Aitchison TRI00000022_C, pages 0106–0107, paragraph 327]. It appears that there was both a positive and a negative aspect to the creation of TEL. The positive was that, at the time that the Tram project was being considered, Edinburgh had the benefit of a very popular and successful bus company: LB. CEC owned 91 per cent of the shares in this company, with the balance being owned by West Lothian Council, Midlothian Council and East Lothian Council. When TEL was established, LB had no role in the development or operation of the trams because the latter role had been awarded to Transdev Edinburgh Tram Limited (“Transdev”), an experienced operating company whose expertise was considered invaluable in the development and procurement of the project. Nonetheless, it clearly made sense that the new tram service should work with the existing bus service rather than against it. tie and CEC were advised that, in order to avoid falling foul of rules of competition law on concerted practices, it was necessary that the activities to be integrated be carried on by a single economic entity. If the positive aspect of creation of TEL was the opportunity to integrate with an existing and flourishing service, the negative aspect arose out of the concerns as to the attitude of LB to the Tram project and its ability and willingness to act to the detriment of the project.

22.7 There was mixed evidence as to the extent that LB was opposed to the Tram project. Initially it was opposed to the project because it was seen as a threat [Mr Mackay TRI00000113_C, pages 0004–0005, paragraph 10]. Mr Holmes said that it was a constant struggle to get LB to stop conspiring against the project [TRI00000046_C, page 0120, paragraphs 447–448]. Mr Howell noted that Mr Renilson, Chief Executive Officer (“CEO”) at LB, had displayed “hostility” to the Tram project when he was not in charge [PHT00000011, page 33], that it was not possible to have a trusting relationship with him [ibid, page 29] and that he had been an influential early opponent of the scheme [TRI00000129, page 0006, paragraph 16]. He noted that LB was against the scheme and he described its conduct as disruptive. Mr Renilson disputed this and it is, perhaps, to some extent contradicted by Mr Gallagher, who said that Mr Renilson’s input was invaluable [TRI00000037_C, page 0058, paragraph 193]. Mr Mackay said that the decision to bring Mr Renilson to sit on TEL was a deliberate tactic to bring him on board [TRI00000113_C, page 0023, paragraph 78]. As Mr Holmes put it, the purpose was “to ensure he was inside the tent” [TRI00000046_C, pages 0120–0121, paragraph 449].

22.8 There was, however, consensus, that it was necessary to avoid competition between the bus and tram services [Mr Gallagher TRI00000037_C, page 0058, paragraph 193; Councillor Donald Anderson TRI00000117_C, pages 0098–0099, paragraph 250]. Apart from the general observation of Councillor Donald Anderson that other authorities had lost money because of such competition, there was a sound basis for concerns as to competition from LB, because, in the past, that company had acted to frustrate council-sponsored transport projects that LB considered were not in its interests. Although the Central Edinburgh Rapid Transport (“CERT”) project had pre-dated his time on the board of LB, Mr Renilson explained that once the contract to operate the buses on the CERT route was awarded to a rival bus operator, LB decided to saturate the route with high-frequency services with the intention of taking custom away from the rival operator on the CERT route [PHT00000039, pages 188–192]. The party that had been awarded the contract withdrew. In those circumstances, no other operator wished to step in, so the project failed. Mr Renilson thought that the cost to CEC was in the region of £10 million [ibid, page 187]. It was therefore clear that, as well as wielding significant influence, LB wielded considerable power and would use it to undermine even projects promoted by its principal shareholder.

22.9 It is perhaps surprising that this matter was not dealt with by CEC directly. In terms of LB’s articles of association, the power of the directors to manage the business was subject to regulations made by the company in general meeting [TRI00000310,pages 0042–0043, article 27.1]. The extent of CEC’s shareholding was such that it would be able to ensure that a vote to make such a regulation was carried, and it could have given directions to the LB board by this means. It is not within the remit of this Inquiry to investigate the reasons for the reluctance on the part of CEC to manage the situation in this way. For present purposes, it is enough to note that LB was seen as a threat to the success of the project and that the way it was dealt with was to put representatives from LB in a position to make decisions on the Tram project at the procurement and construction stage and to ensure that there was integration of the services.While a desire for integration might dictate that LB would work with tie, it did not in any way justify LB’s being in a position to make decisions relating to procurement and construction of the project.

22.10 The introduction of TEL with its representation from LB was not welcomed by everyone in the Tram project. Mr Howell recognised that TEL was necessary for integration, but said that he was surprised when TEL was put forward as the lead organisation [PHT00000011, page 29]. Mr Kendall said of the creation of, and passing powers to, TEL:

“it was not just hugely disruptive, it was almost debilitating to my ability to be clear and to direct solutions and outcomes and it changed materially the ability that I had to move this project forward at pace and in 2006. It set up a lot of conflict and the major conflict, as I have already alluded to, the major conflict came between myself and Renilson and also Andy Wood who was the only other person who had built and operated a tram scheme before.” [TRI00000136, page 0190.]

22.11 When considering its role below, it is relevant to have in mind that both the Chief Executive of tie and the Project Director were opposed to the interposition of TEL.

22.12 Thereafter, there were a number of developments from time to time, and it is most straightforward to summarise the principal ones in chronological order. Prior to doing so, however, it is useful to consider the guidance that existed at that time in relation to management of projects such as the Tram project.

Office of Government Commerce guidance

22.13 Office of Government Commerce (“OGC”) guidance and the OGC reviews of the project will be considered in Chapter 23 (OGC and Audit Scotland), but it is useful to note here the features relevant to the governance structures adopted for the project. The guidance current at the time included a series of booklets, including “Achieving Excellence in Construction, 02 Project Organisation: roles and responsibilities, (2003)” [CEC02084819]. This guidance was revised and reissued in 2007 [GOV00000003], but the passages quoted below were not materially changed. It identified the following key roles:

- the investment decision-maker;

- the Senior Responsible Owner;

- the project sponsor; and

- the project manager.

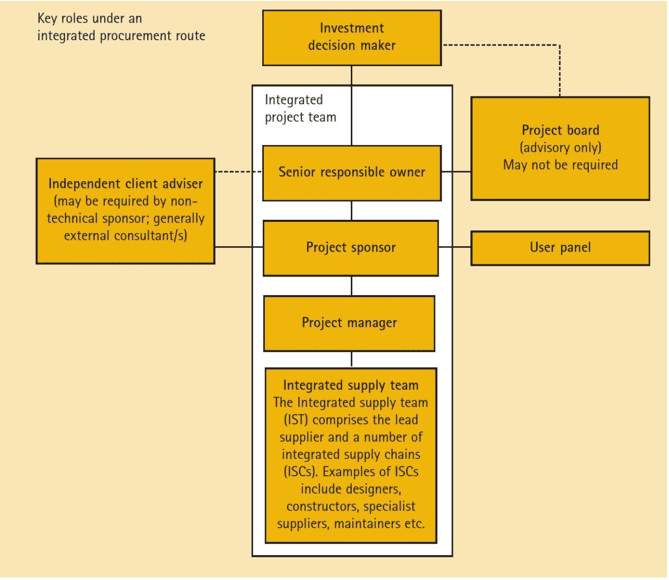

22.14 The Senior Responsible Owner is generally referred to as the “SRO”, and that abbreviation is used in this Report. The guidance stated that the roles and responsibilities of those involved should be clearly defined. It supported a structure with an integrated project team that includes input from the supply team and designers. The guidance noted that this approach would help to encourage innovation and avoid an adversarial culture and would also encourage collective responsibility for a successful outcome. The intention is indicated in a diagram

taken from the booklet, which is reproduced in Figure 22.1.

Figure 22.1: Project organisation: the integrated project team

The guidance noted that a traditional project structure was not integrated, as it separated out the responsibilities of each party, and should not be followed unless it demonstrated significantly better value for money than the recommended procurement routes [CEC02084819, page 0010].

22.15 As is apparent, this places considerable importance on the role of the SRO, who should be a senior manager in the business unit that requires the project. Of this role the guidance stated:

“The senior responsible owner is responsible for project success. This named individual should be accessible to key stakeholders within the client organisation and, in order to reinforce commitment to the project, should also be visible to the top management of the partnering organisations involved. The IDM [Investment Decision-Maker] should ensure that the SRO has the authority that matches the responsibilities of the role.

“The SRO defines the scope of the project, is personally responsible for its delivery and should be accessible to stakeholders. The SRO may be assisted by a project board, to ensure that other stakeholders buy in to the project as early as possible. The project board should not have any powers that cut across the accountability and authority of the SRO. Project boards should be advisory only, addressing strategic issues and major points of difficulty. If a major issue cannot be resolved with the SRO, project board members would have recourse to the IDM. The SRO must form part of a clear reporting line from the top of the office to the project sponsor.” [ibid, pages 0012–0013.]

22.16 In relation to the role with other entities and persons in the delivery team, the guidance stated:

“The SRO should be committed to encouraging good teamworking practices within the client organisation and with other organisations involved with the project, to ensure that the whole project team really is integrated – client and supply teams working together as an integrated project team. In particular, the SRO should give clear, decisive backing where the client enters into partnering or teamworking arrangements with the integrated supply team (consultants, constructors and specialist suppliers) during the life of the project.” [ibid,page 0014.]

22.17 The guidance does not use the term “project director”, but does refer to the “Project Manager” as the person who leads the project team on a day-to-day basis. The SRO’s role is obviously distinct from that of the Project Manager. It is notable that, in the guidance, the role of the project board is purely an advisory one, assisting, and chaired by, the SRO.

22.18 The Guidance emphasised that lines of reporting and decision-making should be as short as possible and also very clear. It was also stated to be important that delegations and individual responsibilities for decision-taking should be clearly established at the outset of the project and understood by everyone involved in it. It stated that experience had shown that, where these conditions were not met, the likelihood of conflicting, poorly informed or delayed decisions would significantly increase the risk of failure of a project [ibid, page 0009].

PRINCE2

22.19 The OGC also issued guidance on best practice in project management. That advice was called “PRojects IN Controlled Environments” (“PRINCE2”) and applied to all projects (ie it was not restricted to construction projects). It was used extensively by the UK Government [GOV00000029, page 0002]. Ms Andrew said that this was used on all major CEC projects [PHT00000005, page 46; TRI00000023_C, pages 0022–0023, paragraph 20(2)], and Mr Poulton analysed the roles of the various participants in terms of it [PHT00000051, pages 61–65]. On the other hand, Mr Heath of OGC said that he did not recall any mention of PRINCE2 in relation to the project [PHT00000009, page 22]. On any view, however, it is relevant background against which to consider the arrangements that were put in place.

22.20 As with the OGC guidance considered above, it is a project method that considers more than just the structures used to deliver the project. A key feature of PRINCE2 is the need for independent project assurance. It stated that while the project board was responsible for project assurance, it might find it beneficial to delegate project assurance to others, as members of the board did not work full time on the project and, therefore, placed a great deal of reliance on the project manager. The guidance stated:

“Although they receive regular reports from the Project Manager, there may always be questions at the back of their minds: ‘Are things really going as well as we are being told?’, ‘Are any problems being hidden from us?’, ‘Is the solution going to be what we want?’, ‘Are we suddenly going to find that the project is over budget or late?’, ‘Is the Business Case intact?’, ‘Will the intended benefits be realised?’ … All of these points mean that there is a need in the project organisation for monitoring all aspects of the project’s performance and products independently of the Project Manager. This is the role of Project Assurance.” [GOV00000029, page 0033.]

22.21 Although this is relevant as background, it is the governance structures that are of concern here. In relation to that, the PRINCE2 method identified three project interests:

- the business;

- the user; and

- the supplier.

22.22 The business, which may also be seen as the customer, is the interest that decides to proceed with the project and makes available the funds for it. The business interest therefore must take the decision as to whether the benefits of the project are such that it is worth committing expenditure to it. In relation to the Tram project, the business interest is most obviously represented by CEC, although a large part of its responsibilities was delegated, initially at least, to tie. As the name suggests, the user is the entity that will make use of whatever is delivered by the project. As matters stood at the start of 2005 and through to August 2009, that was Transdev – the appointed operator. Later, the contract with Transdev was terminated in favour of TEL’s becoming operator which meant it would have become the user. The supplier interest, again as the name suggests, consists of the people or entities that will provide the project outputs.

22.23 For projects of the size and complexity of the Tram project, the PRINCE2 project management structure below the corporate entities consists of a project board, a project manager and a team manager or managers. The project manager runs the project on a day-to-day basis. The project manager may delegate responsibility for certain elements of the project to particular team managers, just as was done in the Tram project.

22.24 The project board should consist of representatives of the three interests in the project. These interests will be represented by the Executive, the Senior User and the Senior Supplier. The Senior User is a person or persons who represent the entity that will make use of the output of the project when it is complete. The function of the Senior User is to ensure that, when complete, the project output will meet the needs of those who will use it. The Senior Supplier will be a person or persons who represent the teams that do most of the work. The function of the Senior Supplier role is to be in a position to commit or acquire resources necessary to complete the project. The Senior Supplier role need not come from the customer organisation and may consist of representatives of external contractors as well as, or in place of, internal managers. Applied to the Tram project, it would be expected that representatives from Bilfinger Berger, Siemens and CAF (“BSC”) would be included in the supplier role, as might representatives from Parsons Brinckerhoff (“PB”).

22.25 The third element of the project board – the Executive – represents the business interest. The Executive is a person rather than a group of people and is ultimately in charge of the project. The guidance is clear that the project board is not intended as a democracy in which decisions are taken by a majority [GOV00000029, pages 0028 and 0052–0053]. The decisions are ultimately those of the Executive, and it is that individual who instructs the project managers. In terms of the PRINCE2 method, the Executive is responsible for appointing the other project board roles and chairs the project board.

22.26 I have given only a brief account of the principal elements of the structures identified in these two project management methods. It is clear that there are both similarities and differences in the various roles and workings of the two methods. The purpose of the Inquiry does not require a detailed evaluation of these. What is appropriate is to have an understanding of the background guidance that was deemed to be of some relevance to the Tram project to provide a framework within which to evaluate what was done.

Timeline (July 2005 - December 2009)

22.27 To state all the various decisions in relation to governance and the papers that lay behind them would be a lengthy process, and could obscure the main elements. Setting out even the main events in the changing governance picture requires a reasonably detailed narration of events between 2005 and 2010. In my view, the main events during that period were as follows:

July 2005

22.28 In July 2005, the Chief Executive’s Report to the tie Board anticipated that a Tram Project Board (“TPB”) and an Edinburgh Airport Rail Link Project Board would be set up in respect of their two principal projects [TRS00008524, page 0015]. This was said to be required as the magnitude and frequency of decisions on the project was increasing [ibid, page 0019]. The precise role of the boards was not stated clearly at the time. The tie Board papers said that the project boards would assume responsibility for each project, that they would be the principal decision-making bodies and tie would delegate its powers to them. However, it was also stated that the boards “will not have directive power” [ibid, page 0015]. It was envisaged that

the boards would report to the tie Board. The papers for this meeting also state that “[t]here must be migration of tie Board project responsibility to TEL at the appropriate time in a seamless, controlled way” [ibid, page 0019]. As noted above, TEL was envisaged to be the single economic entity that would facilitate service integration. There was no indication of what the “appropriate time” would be. The paper also noted that delegation to the project board of the principal decision-making authority would come by way of delegation from tie and later TEL [ibid, page 0019].

22.29 At this time, Mr Bissett was working for tie as a consultant and was primarily using his background in finance and business to develop the financial aspects of the business cases. He also had a prime role in developing the governance structures. He said that the intention was that the project boards should be “the primary oversight and challenge body for each of the two projects” or the “primary governance and oversight body” [PHT00000028, page 40]. On the other hand, he said that it was intended that it would replace decision-taking by tie [ibid, page 42]. Despite this, he also said that “tie would still retain the ultimate responsibility for the activities of the Board” [ibid, page 41]. He was asked whether it might be the role of the project boards to facilitate the implementation of the project rather than to take decisions in respect of it [ibid, page 44]. This is consistent in part with what was said in the board papers and is consistent also with the discussion of project boards in guidance on the PRINCE2 model. It does not accord, however, with the statements that it would be a decision-making body. Although Mr Bissett said that it was envisaged that the boards might have this facilitating role, his descriptions of how they would operate suggested that their role would be an executive one in which each member of the board could seek to determine the decision [ibid, pages 40–45].

22.30 At this stage, no statement was made as to the membership of the project boards. Mr Bissett said that it was intended that they would have representatives from CEC and Transport Scotland and would include all the “main parties” or “all of the main stakeholders” [ibid, page 42]. He thought that this would give the persons in question more involvement rather than their just being observers. The consequence of this is that it would be these stakeholders who would be taking decisions in relation to delivery of the trams rather than tie. Asked why this should be the case, he said that tie‘s primary purpose was just to get the project through the development stage to be ready for procurement [ibid, page 43]. I do not accept this. No such limitation on the remit of tie was envisaged when it was established. This was an innovation on what had been intended, and it is notable that it was being brought about within tie rather than by CEC.

22.31 Even at this stage, when the project boards were first proposed, it is apparent that there was a lack of clear expression of their role and their responsibility. The statement that they would be the principal decision-making bodies is quite inconsistent with the guidance in the PRINCE2 model that they would not have directive power. To say that tie would delegate its powers to them indicates that their role would be that previously undertaken by tie and was therefore directive or executive. In terms of the guidance on project boards, however, that is not the proper function of a project board. It appears that what is being done is, in essence, regarding each project board as a mini-tie, which would focus on the single project. There is a further fundamental inconsistency between the statement that powers would be delegated to the project boards and the comment by Mr Bissett that they would have the function of oversight and challenge. If the statement as to delegation of powers is true, the decisions and actions that they would be overseeing or challenging would be their own. This clearly illustrates tie‘s lack of understanding for the need for independent review of actions and decisions in any system of governance. It is also a good example of the confusing and ineffective nature of the governance structures that were proposed from time to time. It is also apparent from the OGC and PRINCE2 guidance mentioned above that neither intended the project board to function as an oversight body. Thus, from the inception of the project board, there was confusion and ambiguity and a departure from guidance without any apparent appreciation that this was being done.

August 2005

22.32 The papers for the tie Board Meeting in August 2005 [TRS00008528,Parts 1–2] stated that a report on governance had been approved at the July board meeting [ibid, Part 1, pages 0005 and 0026] and attached a remit for the TPB [ibid, Part 1, page 0050]. This was described by its author, Mr Bissett, as “not an easy read” [ibid, Part 1, page 0026]. That is an understatement. This remit refers to the board as “a body consisting of the key stakeholders who have influence in facilitating the development and delivery of the Tram Project” [ibid, page Part 1, 0050]. This function is also picked up in the requirement that members of the board will seek to resolve within their own organisation any potential obstacles to the project [ibid, Part 1, page 0052]. It is of note that the paper indicates that the project board will make only recommendations to the tie Board in relation to ongoing governance, project management arrangements and changes to cost and programme. Despite this reference to a facilitative function and the making of only recommendations, the remit envisages that the board will take over most of the authority vested in tie by way of delegation [ibid, Part 1, pages 0051–0052]. It was noted that these arrangements would change when the tie Board handed over formal responsibility to the TEL Board, but Mr Bissett noted that this was to deal with the situation when the service was in place and that tie remained the delivery body [ibid, pages 0051–0053]. It recognised that the TPB was not a legal entity but nonetheless said that it would have powers delegated to it by the tie Board [ibid, page 0058]. There is no mention in this paper of any function of “oversight” in relation to tie. The remit was approved at the August meeting of the tie Board, which recognised that tie could take back the powers and responsibilities of TPB if the latter did not fulfil its remit [TRS00008535, page 0007].

22.33 The reference within the remit paper to the project board’s having a “facilitative” role echoes one of the roles suggested in the July paper. This role is perhaps closer to the intended role of a project board that brings together representatives of the various interests necessary to make the project a success and that provides advice to the principal decision-taker rather than being that decision-taker. The statement that the project board would make recommendations rather than taking decisions is also consistent with the guidance. Once again, however, the remit contains the contradictory statement that the project board would take over the authority of the tie Board. Although the two functions referred to in the paper (facilitation on the one hand, and taking over authority on the other) appear to be at odds, Mr Bissett considered that it was intended that they should do both [PHT00000028, page 48]. I reject this explanation. Instead, that such mutually exclusive comments are contained in the remit suggests that the tie Board participants had not read it or, at the very least, had not taken the trouble to understand it.

22.34 At this stage it was intended that the TPB would comprise:

- the Chief Executive and Project Director from tie;

- the Chief Executive and all non-executive directors from TEL;

- a representative of CEC;

- a representative of the Scottish Executive (this being before the change of name to the Scottish Government and the creation of Transport Scotland);

- a representative of Transdev; and

- Mr Papps from Partnerships UK (a body established by the UK Government to provide advice in relation to management of large construction projects).

22.35 The Chairman of the TPB was initially to be Mr Gemmell, a non-executive director of tie, but it was noted that “in due course” the Chairman would be the Chairman of TEL or a non-executive director of TEL [ibid, page 51].

22.36 The composition of the proposed project board is not consistent with either guidance model. To a large extent, it merely replicates tie and TEL or is a cross between them. This is perhaps unsurprising, in that it is being asked to perform the functions previously carried on by the companies. It raises the issue of why it was thought necessary to have a project board when a body or bodies with similar members was or were performing the same role. That question does not appear to have been considered at the time.

September 2005

22.37 In September 2005, a progress report was produced by tie to the committee of the Scottish Parliament considering the Tram Bills. The report stated that the members of the TPB acted as “champions of the project” within their respective organisations for the progression of necessary permissions and approvals and that the TPB operated under delegated authority from the tie Board and, in turn, provided the Tram Project Director (“TPD”) with delegated authority to deliver the project [CEC00380894, page 0004, paragraph 1.9]. It is hard to see how the TPB could have played an oversight or governance role while its members were also acting as “champions” of the project. The report did not give a clear statement as to what authorisation had been delegated to the TPB and what the remaining role and responsibilities of the tie Board were.

October 2005

22.38 The papers for the tie Board meeting for October 2005 [TRS00008535] again contain statements that are hard to reconcile [ibid, pages 0030–0031 and 0043]. The TPB was noted to be the primary decision-making forum and also the oversight body for the project, but nonetheless tie retained overall responsibility for the quality of tie‘s service delivery and for fundamental matters affecting the project [ibid,page 0030; Mr Bissett PHT00000028, pages 61–62]. Also, decisions of the TPB were to be reported to the tie Board for ratification, and the TPB was to be seen as a committee of the tie Board so as to enable the delegation of powers [TRS00008535, page 0043]. When asked about the number of bodies – CEC, tie, TEL and the TPB – Mr Bissett accepted that there was overlap and that having four layers in the hierarchy was “less than efficient” [PHT00000028, pages 62–63].

22.39 The same defects in the earlier two papers appear here also. It is hard to see how it was intended to reconcile the notions that:

- the TPB was the decision-maker, but was also providing oversight;

- the TPB was the decision-maker, but tie retained responsibility; or

- the TPB was the decision-maker, but its decisions would require ratification by tie.

22.40 It was apparent from the TPB membership suggested in August that most of the members of the TPB were not drawn from tie.There was also nothing to suggest that tie could change the membership of the TPB. It was also clear that further debate of issues before the tie Board would be the exception. This makes it odd that tie would retain responsibility for the decisions taken.

22.41 The role for the TPB that was being developed in this paper meant that it was not apparent who was to play the role of the executive or the SRO. If the decisions were to be taken by the TPB collectively, the result would be the loss of individual accountability that is a feature in both the OGC guidance and PRINCE2. This was not considered in the review. Having the TPB as the body that would take decisions may be the reason that BSC and PB were not represented on the TPB to represent the supplier interest. It may have been felt that they could not participate in making decisions as to how affairs under the contracts with them should be conducted. That need not have been an issue if the role of the project board had been limited as had been suggested in the guidance.

November 2005

22.42 The minutes of the meeting of the TPB in November 2005 (as a sub-committee of the tie Board) dealt not with the structures that were to be in place but where the responsibilities lay [TRS00002067]. They noted that TEL will “hold the mantle of control and ownership post financial close”[ibid, page 0002, paragraph 3.1]. This would obviously be much earlier than taking responsibility once services commenced and would mean that TEL had control during construction. No justification was given for taking responsibility for construction of the tram infrastructure away from tie and giving it to TEL. The minutes noted that TEL, tie and the TPB would work together. They did not explain how, but noted that the matter was to be considered at a meeting of the TEL Board which it was said would follow on from the TPB meeting. The Inquiry has been unable to find any minutes of such a meeting, but a note of a meeting of the TPB in December 2005 noted that a paper concerning governance was presented to the TEL Board on that date, but no substantive discussion had taken place then or since [TRS00002065].

22.43 The attendance list for this meeting of the TPB recorded the presence of representatives of tie in addition to the persons who in the previous month had been said would make up the board. This appears to be a further indication of a lack of clarity about the constitution and function of the TPB.

January 2006

22.44 In the minutes of the TPB of 23 January 2006 the merger of the TEL Board and the TPB was recorded, and it was recognised that there had to be clear governance for decisions to be made [TIE00090588, page 0002]. Having created the TPB as a separate body to assist in construction of the Tram project, it is odd both that it was being merged into a board of directors and that the board in question was that of TEL. Mr Bissett, who is recorded as being present at the meeting in January, could not recall why this had been decided. Even if it was now considered that TEL rather than tie was delivering the tram infrastructure, the company board and the project board had distinct functions and different membership. This merger shows that this was not properly understood at the time.

February 2006

22.45 A paper entitled ‘Proposed Governance Structure’ [TRS00002175] set out proposals that differed from those from November 2005 and were said to incorporate TEL fully into the project and produce governance and a decision-making structure “which reflects clear project roles and responsibilities”. These entailed that TEL would undertake to CEC to deliver the tram system integrated with other modes of transport, and tie would be responsible to TEL for delivery of the trams. tie would deliver services “on behalf of CEC”. It assumed that tie would enter into the contracts for construction of the tram system and delivery of the tram vehicles, but that these would be novated to TEL once operations commenced. Despite the statement in the January minutes noting the merger of the TPB with the TEL Board, this paper described it as a proposed situation. Amalgamating the two would mean that instead of tie delegating responsibilities to the TPB, the TPB would be part of the body that owned tie [PHT00000028, page 73]. It noted that the decisions of the merged body would be taken solely by directors of TEL. This meant that, in effect, TEL had been put in charge and tie was taken out of the picture [ibid, pages 75–76], and the paper noted that “TEL has effectively stepped into tie’s shoes for the tram project”. Mr Bissett acknowledged that he could not now see the advantages in this change [ibid, page 75]. Despite the transfer of responsibility, the paper noted that TEL was not to employ a management team other than its CEO.

22.46 At the same time as proposing the merger of the TPB and the TEL Board, this paper proposed that TEL Board meetings should routinely be attended by the TPD, other tie operational management, other CEC representatives, Transdev representatives, a representative of the Scottish Executive and Mr Papps. This, in effect, brought it directly into line with attendance at the tie Board. This further obscured the point of the changes and blurred the distinction between the various entities. There was still no representation of the supplier interest.

22.47 Although the paper sought to incorporate TEL into the management structures for the project, it provided no justification for this. As was mentioned in paragraph 22.45 above, the paper stated that “TEL has effectively stepped into tie’s shoes for the tram project” [TRS00002175, page 0003], but did not say why this was or should be the position. As I have noted above, having regard to the purpose for which TEL was created and the expertise of the persons recruited to it, there is no apparent reason why it should take over responsibility for construction works. There was no explanation of the benefit that would arise from having tie enter into all the contracts and provide its services to TEL. It is of note that at this stage almost all the employees were engaged by tie and it was tie that was in receipt of the monies from CEC, including those that had been provided by Scottish Ministers. That being so, one would have expected a reasoned statement of the rationale for a new body being included in the structure. While it might be expected, it was not given. One is left with the feeling that it was simply an attempt to bring LB into the project to head off potential opposition and difficulty.

March 2006

22.48 Although the February paper entitled ‘Proposed Governance Structure’ was approved by both the tie and TEL Boards that month, a revised version was prepared in March 2006 [TRS00000330]. The following are the principal changes that it made to the structure that had been agreed the previous month.

(a) There was no longer express provision that tie would be providing its services to TEL, although it was not clear to whom services would be provided.

(b) In the structure set out in February, tie was said to be providing services to TEL on behalf of CEC. This appeared to indicate that TEL stood in the shoes of CEC as the recipient of the services. In the March structure, tie was to deliver the project “on behalf of CEC”, which appeared to indicate that the services were provided to CEC.

(c) It recorded that TPB had already been merged with TEL and stated that the TEL Board’s authority (and therefore, by necessary implication, the TPB authority) was exercisable by TEL’s CEO.

(d) A sub-committee of the TEL Board was formed to issue guidance to the TPD and individual work stream leaders. This indicated that it was the collective body rather than the individual that was in charge and is the opposite of what is contained in the guidance.

(e) While tie was to remain the counter-party for all contracts until service commencement, the terms of those contracts were to be subject to approval by TEL “in its project Board role”. This maintains the odd position that the party that had the ultimate say on decisions was not the one incurring contractual obligations.

May 2006

22.49 A project readiness review carried out by the OGC in May 2006 [CEC01793454] noted that the governance structure was complicated compared with best practice. By way of explanation, the review stated:

“A best practice project governance structure would consist of an empowered project team under the direct control of an empowered and accountable project director. The project director would report to a project board chaired by the Senior Responsible Owner (‘SRO’) for the project on behalf of the project promoter.

“The project board and the project director would have clear terms of reference in respect of their respective responsibilities delegated from the project stakeholders.

“The OGC describes the role of the SRO as ‘the individual responsible for ensuring that a project or programme of change meets its objectives and delivers the projected benefits. They should be the owner of the overall business change that is being supported by the project. The SRO/PO should ensure that the change maintains its business focus, has clear authority and that the context, including risks, is actively managed. This individual must be senior and must take personal responsibility for successfully delivery of the project. They should be recognised as the owner throughout the organisation.‘” [ibid, page 0006, paragraph 3.1.]

22.50 The review recommended that a TPB be set up as a matter of urgency and that there be clarity as to the identity of the SRO. It also said that the TPB should be the only body through which key decisions on the project scope should be taken.

22.51 From the terminology used it is clear that it is OGC guidance rather than PRINCE2 that is being applied. In that compliance with the recommendations of these reviews was a condition of the grant monies being made available by the Scottish Ministers, there should have been some impetus to adhere to the OGC model.

22.52 As was noted in paragraph 22.15 above, the OGC guidance refers to the SRO as merely being “assisted” by the project board. The OGC review does not state expressly where the executive power would lie. It did not say that all project decisions should be taken by the board, but it clearly accords it primacy. Oddly, therefore, the review appears to contemplate a different structure to that stated in the OGC guidance. It may be relevant that Mr Heath, who was a member of the team, was unaware of the OGC guidance until it was sent to him by the Inquiry [PHT00000009, pages 7–13]. No basis was stated for departing from the Guidance and doing so is likely to have added to the uncertainty surrounding the role of the project board. The apparent predominance afforded to the project board in this Review adds to the difficulty in determining the role of the SRO. As with the structure proposed in March 2006, it adopts collective responsibility in place of individual responsibility and this gives rise to the danger that, with a number of people and interests involved, there is a culture in which each person assumes that someone else is exercising judgement and control. As will be apparent from the discussion below, that is what happened.

22.53 In relation to the recommendation that there should be a project board at all, it will be apparent from the foregoing that, in fact, such a board had been in operation for some time. However, this fact may have been obscured as a result of the board’s having been merged with TEL and being composed of the same people as the board of tie or TEL rather than following the OGC guidance. It appears, however, that, up to this time, there had been no SRO. The papers submitted to tie and to the TPB in relation to guidance prior to this time had not made mention of the SRO, by way of identifying either the role or the person who performed it. Although Mr Howell thought that Mr Kendall might have been designated SRO [PHT00000011, page 37], there is no record of this and, as Mr Howell appeared very tentative in his views on this matter, I conclude that he was mistaken in this regard. This means that the only oversight by an individual would come from the Monitoring Officer appointed in relation to tie‘s operating agreement with CEC. At this time, it appears that, in terms of that agreement, the Monitoring Officer would be concerned with the company rather than the project as a whole so there was no one performing the SRO role.

22.54 Following the review, Mr Renilson, then the CEO of TEL, was appointed as SRO. This is confirmed in a number of papers on guidance prepared by Mr Bissett, which came later and will be considered below. It was also noted in a later readiness review conducted by OGC in September 2006 [CEC01629382, page 0005]. Mr Renilson interpreted the role as requiring him to use his best endeavours to “make the project happen” [PHT00000040, page 91]. However, he considered that his role as SRO related only to the period when the tram would be operational and not the construction period [TRI00000068_C, pages 0039–0040, paragraph 129]. I have seen no evidence that could justify his belief that his role was so limited but, on any view, the result was that no one was performing the SRO role during that stage. This should have been apparent to all the members of the TPB, and I find it extraordinary that nothing was said at the time. Had the issue been noted then, either Mr Renilson would have started to perform the role or another person could have been appointed SRO in his place. Allowing the project to proceed in the absence of someone to perform this key role – or the equivalent of the Executive in PRINCE2 terms – was a fundamental defect in the governance arrangements. It meant that there was no single person with responsibility for the project and the focus that could be expected from an active SRO was absent.

22.55 Even if Mr Renilson had undertaken the role assigned to him, the situation would still have been far from ideal. TEL became a delivery organisation as the project governance developed and Mr Renilson was its Chief Executive. In my view it is better for an SRO, as the person with ultimate responsibility for the project, to be someone within the client that is commissioning the work, or the end user of what is provided – they should be on the outside looking in. As such, they have some objectivity in relation to the actions of the entity or entities responsible for delivery. It would have been most appropriate to have had an SRO from within CEC because the project “belonged” to CEC. This would have addressed the issue of unsatisfactory reporting to CEC. As I will consider below, the alternative of reporting from the TPB to the CEC Tram Sub-Committee was not satisfactory for this purpose.

June 2006

22.56 A further paper prepared by Mr Bissett on governance – this time for the TEL Board meeting in June 2006 – was intended to address the position through to financial close [CEC01803822]. It said that the “fulcrum” of the project was the TEL Board’s “[acting] as the Tram Project Board” [ibid, page 0001; PHT00000028, page 83] and that the authority for the Project Director came from TEL. tie was noted to be the “delivery agent” specified by CEC acting through TEL. Although the TPB and the TEL Board had been merged, this paper noted that it was necessary to have more clear demarcation between TEL as the project board and TEL in its other capacities. It said that TEL was an element of the “project approval” part of governance but also, as the project board, at the project execution level. To achieve demarcation, it was proposed that the project board would revert to the title of the TPB and would be a formal committee of the TEL Board. The paper indicated that Mr Mackay, the non-executive Chairman of TEL, was to chair the TPB. The remainder of the membership would consist of:

- Mr Renilson, the TEL CEO and SRO;

- Mr Gallagher;

- Mr Harper, the Project Director;

- Mr Campbell, a director of TEL and LB;

- a CEC representative;

- a Transport Scotland representative; and

- other advisers as required.

22.57 This paper noted that the need to identify an SRO was one of the issues that required to be addressed. It stated:

“The TEL CEO has overall responsibility to ensure project execution is working effectively. As such he would be the Senior Responsible Owner (SRO) under OGC guidelines and is the lead operational director on the Tram Project Board. This does not precisely fit OGC guidelines, which would for example call for the SRO to chair the TPB, but is a practical approach appropriate for this project.” [CEC01803822, page 0002.]

22.58 It referred to Mr Renilson as being the SRO [ibid, page 0003], and there is no doubt from this that this role covered the construction phase as well as the operational phase. Mr Renilson was a director of TEL and would have received a copy of the paper. Whatever had been the position prior to this it meant that he should have been aware of what was expected of him in that role.

22.59 Mr Bissett was asked about the development of the business case that was ongoing at this time, and he explained that that was the responsibility of the Tram project team employed by tie, but once approved at that level it would “move through the hierarchy to the Tram Project Board and ultimately TEL to give its seal of approval if it thought appropriate to the Council” [PHT00000028, page 87]. Mr Bissett recognised that the various layers were duplicative. In terms of the guidance noted above, it should have been the SRO who had responsibility for the business case.

22.60 If the re-emergent TPB took a decision in relation to implementation of the project, it would do so as a sub-committee of the TEL Board. That decision could take effect within TEL and then tie would, in effect, require to be instructed to implement the decision [ibid, page 90]. The complexity of this is obvious. Mr Bissett said that the process worked better in practice than it appeared on paper, which he attributed to:

“the consistency of membership by senior people of the Tram Project Boards. So, for example, the Tram Project Board meeting to address the tram project would be, give or take two or three hours, possibly longer than that at some points, whereas the TEL Board, which had the same people, had been represented as attendees on Tram Project Board meetings to avoid having two meetings about the same topics.

“So the TEL Board meeting was actually a fairly limited affair. They had statutory legal responsibilities, obviously, but they didn’t have to revisit the entire conversation about the tram project.

“So in practical terms, it wasn’t as duplicative as it may appear on paper.”

[ibid, pages 90–91.]

22.61 Mr Bissett did not accept that a situation in which both bodies would have to consider the issue and had to rely on overlaps in membership to avoid repetition indicated that something was amiss. Mr Bissett did not accept that there was a lack of clarity as to which body was taking which decisions and/or providing advice to CEC. I consider the issue of the overlaps of membership in more detail in paragraphs 22.92 and 22.93 below.

22.62 The paper also noted that two sub-committees of the TPB were established. One of them – the Design, Procurement and Delivery (“DPD”) Sub-Committee – was to be headed by Mr Gallagher, the Executive Chairman of tie [ibid, pages 92–95]. This further complicated the decision-making path. The DPD Sub-Committee under Mr Gallagher could take a decision that would advise the TPB, a sub-committee of the TEL Board. In order for a decision to take effect it was necessary that TEL give a direction to tie under the chairmanship of Mr Gallagher. It may be said that formal steps were not required to achieve this, but it remained the position that there was a very complex structure and that reliance on informal directions or instructions usually creates scope for misunderstanding and confusion.

22.63 The paper continued the approach that the TPB was to have executive rather than advisory powers, which, as I have already noted, did not conform to the OGC guidance. The decision to have someone in a non-executive role (Mr Mackay) chair the TPB was also at odds with either the OGC or the PRINCE2 guidance. According to both, the chair of the TPB was someone with core executive role and responsibility. Further, as the function of the TPB and the SRO/executive was to instruct the project director, it is odd that the project director was a member of the board rather than reporting to it. The basis for recommendation as to the membership of the TPB was not stated and is not clear. Once the non-executive chairman and the project director are left out of account it is apparent that although there were people involved who had experience of managing LB (Mr Renilson and Mr Campbell) the only person who might have had experience of a large construction project would be the representative from Transport Scotland. As I noted in Chapter 3 relating to the involvement of Scottish Ministers, however, Transport Scotland’s involvement in the project was later brought to an end.

August 2006

22.64 The minute of the meeting of the TEL Board on 21 August 2006 [CEC01794941] suggested that the TPB would be separated from TEL. This had been considered as an option in the previous document, and Mr Bissett noted that there was a recognition that the TEL Board had not yet arrived at the best structure for the future [PHT00000028, page 97].

22.65 In this month, Mr Gallagher was appointed as Executive Chairman of tie, having been made Non-Executive Chairman the previous month. Mr Gallagher said that that was because the political uncertainties surrounding the project meant that it would be difficult to recruit a Chief Executive to replace Mr Howell. The dual role was intended to be an interim arrangement, but it remained in place until Mr Gallagher resigned in late 2008. Having one person serve as both Chairman and Chief Executive does not comply with the code on good corporate governance derived from the Cadbury and Greenbury Reports [the Combined Code, Principles of Good Governance and Code of Best Practice, CEC02084834]. This was recognised by CEC at the time of making the appointment, but Mr Aitchison maintained that the departure from good practice was a pragmatic approach in the prevailing circumstances, including the finalisation of the business case [Mr Aitchison TRI00000022_C, pages 0098–0099, paragraph 324]. However, that excuse for departing from the code as to good governance fails to take into account the responsibility of the SRO for the business case. Had CEC recognised the role of the SRO and ensured that Mr Renilson was protecting the interests of CEC by performing that role, the perceived justification for departing from the code would have been shown to be without foundation. Allowing the dual role removed a check that would otherwise have been in place in the period through contract negotiation and execution.

September 2006

22.66 A note prepared by Mr Bissett for the meeting of the TEL Board and the TPB on

25 September 2006 [TIE00000905; TIE00000906] outlined the project governance structure for Edinburgh’s integrated transport system. It noted that the TPB would be an independent entity, rather than a sub-committee of TEL as had previously been said to be intended. The TPB was to have full authority delegated from CEC. The document setting out the new structure stated that this was to be formalised by the TEL Board’s approval of the paper. This is questionable: the decision of the TEL Board might have been effective as between it and the TPB, but the authority of CEC would have been required for such a delegation. On any view, this intention that there be delegation from CEC indicates that an executive function was intended for the TPB. The covering memorandum, on the other hand, said that the members of the TPB were to be empowered by their organisations to take decisions rather than by CEC. This suggests that they could bind only those organisations and is suggestive of a facilitative function. It is therefore apparent that there was still no clarity as to the role that the TPB was to play.

October 2006

22.67 The minutes of the TPB for October 2006 [CEC01355258] noted the approval of a new governance structure. That structure is described in a paper that had been sent to the tie and TEL Boards in August [CEC01758865]. It set out the structure which it was said would take the project through to financial close. It also described the key bodies as being the TEL Board, the TPB and the two TPB sub-committees – tie was no longer identified as a key body. The paper stated that TEL would make recommendations to CEC as to the project. It also stated that:

“The TPB is established as an independent body with full delegated authority from CEC (through TEL) and TS to execute the project in line with the remit set out in Appendix 3. In summary, the TPB has full delegated authority to take the actions needed to deliver the project to the agreed standards of cost, programme and quality.” [ibid, page 0002.]

22.68 The remit in Appendix 3 gave the TPB responsibility:

“To oversee the execution of all matters relevant to the delivery of an integrated Edinburgh Tram and Bus Network with the following delegations:

a. Changes above the following thresholds

i. Delays to key milestones of > 1 month

ii. Increases in capital cost of > £1m

iii. Adversely affects annual operational surplus by >£100k

iv. is (or is likely to) materially affect economic viability, measured by BCR impact of > 0.1

b. Changes to project design which significantly and adversely affect prospective service quality, physical presentation or have material impact on other aspects of activity in the city

c. Delegate authority for execution of changes to TEL CEO with a cumulative impact as follows:

i. Delays to key milestones of up to 1 month

ii. Increases in capital cost of up to £1m

iii. Adversely affects annual operational surplus by <£100k pa

iv. is (or is likely to) materially affect economic viability, measured by BCR impact of <0.1″ [ibid, page 0006].

22.69 Even within this remit, the conflict as to the role of the TPB is notable. It is first said to be the body with authority to execute the project and then it is stated that it is there to oversee what is done by others – presumably tie.

22.70 When asked about the contents of this paper, Mr Bissett said that the function given to the TPB was that which had been originally given to tie, but this is far from clear from the paper’s terms. tie had been created to execute the project, and this paper cannot make up its mind as to whether the TPB was there to execute the project or to oversee execution. Mr Bissett sought to modify his position by saying that the TPB was overseeing the project team employed by tie rather than undertaking the delivery itself [PHT00000028, pages 105–107]. This merely reinforces the confusion and is clearly at odds with the statement in the paper that the TPB would “execute” the project [CEC01758865].

22.71 The paper suggests the following as the membership of the TPB:

- chair

- senior Transport Scotland representative

- senior CEC representative (“Senior User Representative”)

- TEL CEO and project SRO

- tie executive chairman and TEL operations director (“Senior Supplier Representatives”)

22.72 The titles noted in brackets were said to be the ones that accorded with the OGC guidance as to composition of a project board. This is an error. The designations in brackets conform to the PRINCE2 guidance. The term “SRO”, on the other hand, does come from the OGC guidance and not from PRINCE2. This betrays a further lack of clarity as to the model that was being employed. The identified “Senior Supplier Representatives” are not people who fall within the term “Supplier”, as it is used in the PRINCE2 guidance. Neither was CEC the “User” in terms of that model, as people from Transdev (or possibly TEL) should have been the “User” and CEC, or tie in its stead, the “Business” or client. I further consider the issue of membership below, but my impression is that first a decision was made as to who to include and then an attempt was made to fit designations from the guidance to them.

22.73 The decision no longer to consider tie a key body in favour of TEL and its board sub-committees is puzzling. In reality, tie was the body that employed almost all the people to carry out the work necessary to deliver the project. It was also the body that was seeking tenders for the infrastructure and tram works. It was the body that had entered into the System Design Services contract. It was the only body in receipt of funds from CEC; TEL obtained its funding from tie. Anything that TEL was to do would, in reality, be done by tie. All the recommendations that TEL might make to CEC would depend on work carried out by tie, and it is not apparent that the TEL Board would be in a position to interpret information provided by tie employees and consultants so as to reach a different view. This factor means that the recommendations must inevitably arise within tie but would be “rebadged” as though they had come from TEL. Mr Bissett said:

“tie would make the proposals through the Tram Project Director to the Tram Project Board, which is where the main discussions on any issues took place. And the Tram Project Board formally reports up to TEL and to the Council.” [PHT00000028, page 108.]

22.74 No reason was given as to why there should be such a bureaucratic and complex process. It is of note, however, that such processes were apparent elsewhere in the management structures of the project, and most strikingly in the process for giving approval to execute the Infrastructure contract (“Infraco contract”) and the tram vehicle supply and maintenance contract (“Tramco contract”). The structure that was put in place appears quite artificial and does not reflect the reality, which is that recommendations and advice would come from tie. In response to questions as to

the difficulties that might arise where formal structures do not match the practice,

Mr Bissett said that “informal communications are very often very important in project delivery” [ibid, page 107]. In my view this is yet another unfortunate example of something that is a feature in the Tram project: attempts to rely on informal procedures and communications when it is noted that the formal ones are defective or unsuitable.

Audit Scotland report

22.75 In June 2007, after the Scottish Parliament election, at the request of the Cabinet Secretary for Finance (Mr Swinney) the Auditor General for Scotland published his review of the Edinburgh transport projects [CEC00785541]. This will be considered in more detail in Chapter 23 (OGC and Audit Scotland). In relation to the Tram project, Audit Scotland’s report concluded that arrangements put in place to manage the project appeared to be sound, with “a clear corporate governance structure” and “clearly defined project management and organisation”. Unlike the internal TPB paper from October 2006 [CEC01355258], Audit Scotland’s report described tie as one of the “key players”. The report recorded that the TPB exercised overall governance and had the authority needed to deliver the project to agreed cost, timescale and quality standards. This was clearly an executive rather than a facilitiative role. The report said that the authority was delegated to it by CEC via TEL. This is the only identified role for TEL in the governance structure. It is apparent that the structure as narrated by Audit Scotland is not that which had been put in place the previous October. Mr Aitchison noted that what was said about the role and authority of the TPB was not accurate at the time that it was made [TRI00000022_C, page 0106, paragraph 326].

22.76 From the comments that I have already made, it will be apparent that I do not agree with the positive assessment made by Audit Scotland and as matters were to turn out, the confidence expressed was clearly unfounded. This could be partly as a result of the changes made to governance after the report. It could also be a feature of the limited time available to produce the report. Even allowing for these factors, however, in view of the patent lack of clarity as to the roles to be undertaken by each body, the errors in the statements as to the role and authority of the TPB and the unexplained demotion of tie, I would have expected the report to have included a note of caution or a note of the need for further work to be undertaken.

22.77 The effect of the report from Audit Scotland was to engender a confidence in the ability of tie to complete the project [Mr Aitchison ibid, pages 0086, 0088–0089, paragraphs 260, 264 and 267]. Councillor Balfour noted that councillors had drawn comfort from the report [TRI00000016, page 0066 and 0025–0026, paragraphs 66 and 74]. Even people within tie appeared to draw support from it. Mr Bissett said:

“Audit Scotland performed what I regarded as a very thorough review in (I think) 2007, of the governance system that was put in place. I recall they reported positively and I was encouraged to know that tie and the Council were on the right track in respect of this.” [TRI00000025_C, page 0022, paragraph 58.]

22.78 Mr Bissett would have been aware of the timescale within which Audit Scotland performed its role. I do not see how he could have regarded it as very thorough. More importantly, however, if there was satisfaction on the part of Audit Scotland it is all the more remarkable that, within months, major changes had been made to the governance arrangements. The false confidence that the report created was unfortunate, in that it meant that chances to examine and improve the governance structures were lost.

July 2007

22.79 In July 2007, following Scottish Ministers’ decision to withdraw from involvement in the project, Mr Inch sent a briefing paper to the CEC Chief Executive, Mr Aitchison [CEC01566497]. This was considered in further detail in Chapter 13 (CEC: Events during 2006 and 2007). Mr Inch noted that the arrangements in place were complex, and expressed concern about them. He also questioned whether CEC could competently delegate powers to TPB and observed that having a company (TEL)

that was not integrated into the decision-making process as part of governance

was inefficient. He said:

“it is now vital that more rigorous financial and governance controls are put

in place by the Council given the funding cap that has been placed on the

project and the greater financial risks that are to be borne by the Council.”

[ibid, page 0008.]

22.80 Although he recognised that there might be other options, he canvassed three:

- winding up tie and transferring appropriate staff to CEC;

- tie’s continuing to progress the project on the basis of a fully documented principal/agent agreement with CEC; and

- establishing a Tram Committee, which would meet on a four-weekly cycle, to replace the TPB and perform its duties.

22.81 It is significant that, in mentioning the second option, Mr Inch commented that

“TS have previously urged the Council to implement a more robust monitoring of TIE’s activities in delivering the project” [ibid]. It would appear that CEC failed to

act in that regard.

August 2007

22.82 It is highly relevant that, in mid-2007, CEC had some appreciation of the need for better governance. The concerns expressed by Mr Inch appear to have led to a paper being prepared by the CEC Chief Executive, Mr Aitchison, for the August 2007 meeting of the Full Council [CEC02083490]. That paper notes the approval that had been given by the Auditor General to the governance arrangements, but nonetheless states a need for rigorous financial and governance controls to be in place. This, too, was considered in further detail in Chapter 13 (CEC: Events during 2006 and 2007). Throughout the paper there are repeated statements that there has been a change in the risk to CEC as a result of the Cabinet Secretary’s statement that a grant of no more than £500 million could be provided. As I noted in Chapter 3 (Involvement of the Scottish Ministers), in fact there is clear evidence that there had always been a cap, despite any aspirations from CEC or tie to the contrary. I consider that this should have been apparent to Mr Aitchison and others in CEC. On any view, however, it could never have been thought that the Scottish Ministers would bear the whole of the cost increase, so that CEC would be exposed to increased costs to some extent. It is therefore not clear why risk issues should necessitate a review of governance. In particular, there does not seem to be any proper basis for the statement in the papers that:

“Following the change in the risk profile for the Council, the role of the Tram Project Board requires to be considered afresh.” [ibid, page 0003.]

22.83 For completeness, I add that although the paper states that the TPB was a requirement of Transport Scotland, it is apparent from the documents noted above that this is incorrect.

22.84 Although the paper notes the need for rigorous financial and governance controls, it did little to identify what should be done. It reiterated that it was intended that TEL should have the role of integrating bus and tram services and that tie was project managing and would have a role in both the procurement and construction phases. It stated that tie‘s role would be one of agency of the CEC and that it would be set out in clear written terms. It said that senior Council officials had met their counterparts in tie and agreed measures to “clarify the relationship between the two parties in the next phase of the contract” [ibid], but it did not say what had been agreed. There was no mention of the changes that had already been made by tie and TEL to reduce the role and relevance of tie. It indicated that operating agreements would be concluded with each company to formalise and define its function but did not give an outline as to the contents of these documents.

22.85 In relation to the councillors, the paper stated:

“The role of elected members in project decision-making also needs to be defined. The dynamics of the project have changed following the creation of the cap on funding from Transport Scotland. As a result, it is now appropriate to establish a dedicated Tram Sub-Committee. I will report in September on what powers should be delegated to this sub committee [sic] and what powers should be delegated to officers. In the meantime Council is requested to delegate powers to me with respect to any decisions that may require to be taken. Consideration is also being given to the requirements for the Tram Project Board to report to the Tram Sub-Committee.” [ibid]

22.86 The Tram Sub-Committee will be considered in more detail below and has also been considered in Chapter 13 (CEC: Events during 2006 and 2007). In that the intention had been to establish an arm’s-length company to deal with implementation, it is odd that the paper assumed that the councillors had any role in project decision-making as opposed to strategic decisions. Although it was not well articulated, it appears that what was intended was a form of monitoring by CEC of the work being undertaken by tie and, perhaps, TEL. If so, that is potentially quite an inroad into the concept of using an arm’s-length company. If there were to be oversight, it would lead to an inference that if CEC was not happy with what it saw, it would give directions to the companies, override decisions or take decisions itself. This being the case, I would have expected there to be a more detailed consideration by CEC as to the purpose of this oversight and how it affected the role of the companies. Despite this and

Mr Inch’s concerns, no attempt was made to grapple with the issues fully, to clarify

or simplify the structures or to take control away from tie, TEL or the TPB.

September 2007

22.87 In September 2007, Mr Bissett wrote a further draft paper on governance for tie, TEL and the TPB [included in papers for the September TPB meeting – USB00000006 page 0032 onwards] with new structures that, again, were said to be for the period to financial close (then planned for January 2008) and construction [PHT00000028, page 109]. The paper stated that it updated the governance structures from a year earlier and described the structures as having been agreed. The recommendations in the paper were adopted at the September 2007 meeting of the TPB [CEC01357124, Part 1, page 0006]. The paper recorded that Transport Scotland had withdrawn from involvement in the project and that CEC had established a Tram Sub-Committee. The purpose of this was stated to be “to review and oversee decisions with respect to the project” [USB00000006, page 0033]. Despite this, elsewhere in the paper there was reference to making changes in the composition of the TEL Board “to be the active arm of the Council in oversight of project delivery and preparation for integrated operations” [ibid, page 0034]. There was no indication of how this would be related to the role of the Tram Sub-Committee. There was also reference to:

“[t]he emphasis of the TEL Board on oversight (on behalf of the Council) of matters of significance to the Elected Members in relation to project delivery and preparation for integrated operations” [ibid].

22.88 Despite this, the TPB was described as “the pivotal oversight body” [ibid, page 0035]. Apart from the oversight role that it might or might not have, TEL was also said to have overall responsibility to deliver an integrated tram and bus network and, in addition to its oversight responsibilities, the TPB was said to have delegated authority from TEL to execute the project. Thus, each body was charged with both execution and oversight of the project. Needless to say, this was not explained. The paper referred also to the SRO having delegated authority from the TPB. This was a marked departure from the OGC guidance as to the relationship between the two.

22.89 Once again, the TPB was identified as a sub-committee of the TEL Board rather than a free-standing body. The paper recognised that tie now had only one project and proposed that the councillors and other non-executive directors sitting on the tie Board would leave and join TEL or the TPB, but it did not say which. This could have been regarded as material if the two bodies were to have different roles. The intention was that this would leave tie with a board consisting of its chairman and a senior council official. It was envisaged that the Boards of tie and TEL would meet only quarterly.

22.90 Mr Mackay said that the decision to move the councillors to the TPB from tie was his [TRI00000113_C, page 0021, paragraph 71]. This might have been dictated by his view of the role of each of the bodies. In this regard, he said:

“CEC were the owners and they delegated authority to TIE, TEL and the Tram Project Board. tie was primarily design, TEL was integration and the Tram Project Board was the engine room and workhorse, preparing and proposing the detail.” [ibid, page 0019, paragraph 64.]

22.91 This put TPB essentially in the position that tie would have been in at the start of the project. There does not appear to be any foundation for regarding tie as having responsibility only for design either in the governance structures or in the work undertaken generally by tie up to this date.

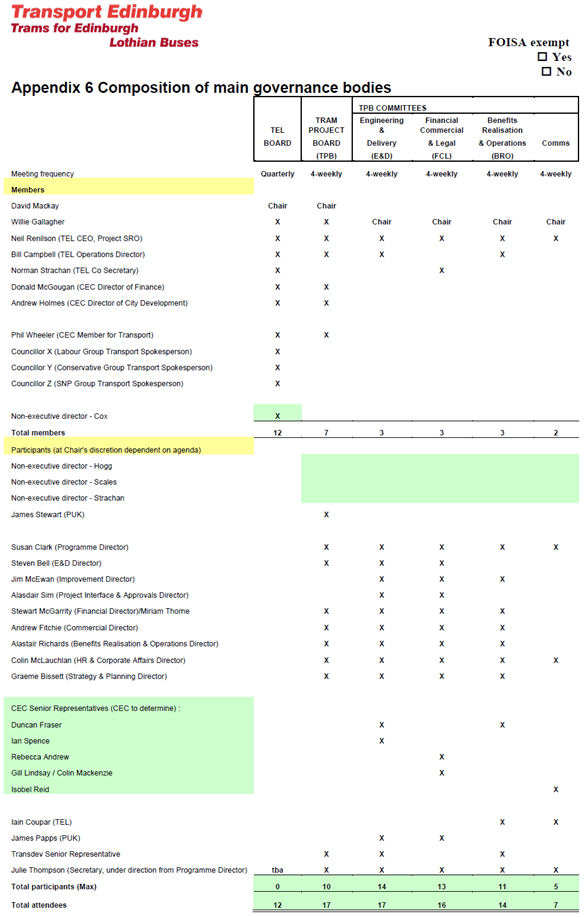

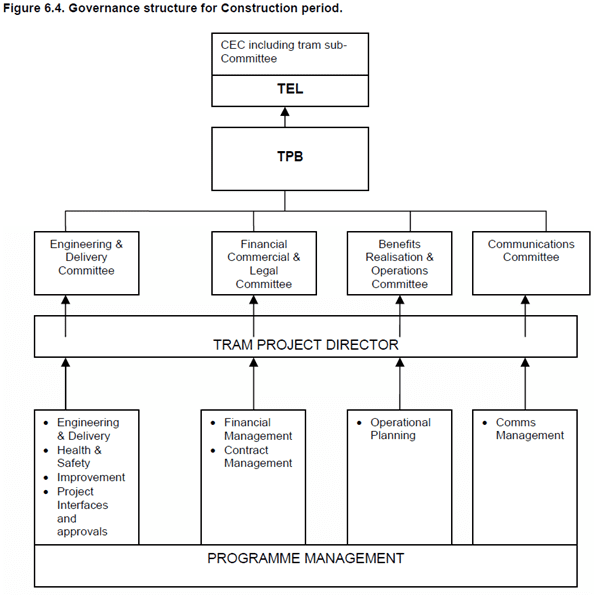

22.92 It is apparent from a table of composition of the boards [USB00000006, page 0042], which is reproduced in Table 22.1, that there is very substantial overlap between the TPB and the TEL Board. Although changes were made to memberships over time, this amply illustrates the extent of the commonality of membership.

Table 22.1: Membership of TEL Board and Tram Project Board

Source: Tram Project Board Report on Period 6, Papers for meeting 26 September 2007 [ibid, page 0042]