Chapter 6: Design (to May 2008)

Introduction

6.1 The procurement strategy was intended to limit the allowance for risk related to design included by the infrastructure contractor (“Infraco”) in the Infraco contract price. The method for achieving this was that, prior to the award of the Infraco contract, tie Limited (“tie”) would enter into a contract for System Design Services (“SDS contract”) with a provider of such services (the “SDS” provider), who would develop the design to a certain level and obtain consents and technical approvals from CEC. The successful bidder for the Infraco contract would complete the design and carry out the construction, installation, commissioning and maintenance planning in respect of the Edinburgh Tram Network (“ETN”). The completion of the design would include the incorporation into the design of the detail of the equipment, components and services to be installed as an integral part of the ETN. The Infraco contract would require Infraco to accept responsibility for design and other work carried out by the SDS provider under the SDS contract. As part of the strategy the SDS provider had to enter into a Novation Agreement (if tie required it to do so), as a result of which Infraco assumed the rights and liabilities of the client (tie) under the SDS contract.

6.2 From the investigations undertaken by the Inquiry it became apparent that issues relating to design arose throughout the Edinburgh Tram project (the “project”), which adversely affected its progress. This chapter and Chapter 7 (Design Following Novation and Contract Close) deal with such issues. For ease of reference they subdivide consideration of design into two separate periods, namely: the period ending with the award of the Infraco contract in May 2008; and the period thereafter.

SDS contract

6.3 Before looking at the various difficulties and delays that were experienced on the design programme during the period prior to the signature of the Infraco contract and the effect of these difficulties on the procurement strategy for the project it is appropriate to consider the SDS contract that was entered into between tie and Parsons Brinckerhoff (“PB”) on 19 September 2005, as a result of which PB became the SDS provider [CEC00839054]. With tie’s prior written approval PB could appoint other specialists to perform part of the SDS services, and did so. Despite any such appointment, PB remained responsible for the services provided under the SDS contract, including those performed by any such appointee [ibid, page 0039, clause 9). Accordingly, throughout this chapter references to the “SDS provider” refer to PB.

Design services

6.4 Design services were to be provided over three phases in relation to both lines 1 and 2, namely:

- requirements definition;

- preliminary design; and

- detailed design [ibid, page 0083, Schedule 1, paragraph 2.2].

6.5 The intention was that each phase would be completed (or, at least, largely completed), and the design for each phase agreed, before moving on to the next [ibid, pages 0032–0036, paragraph 7.3].

6.6 The design services to be provided by PB were set out in Schedule 1 to the SDS contract. In short, PB was to produce the design for the tram network up to the detailed design stage. In relation to some elements, however (such as the electrics and communications), PB was to develop the design up to a certain point, with the detailed version being completed by Infraco, depending on the particular components and systems that formed part of its bid. In relation to other items of design (such as track form and tram shelters), PB produced generic designs that could then be populated with specific components – again, depending on the particular components chosen by the successful bidder for the Infraco contract.

6.7 As well as producing the design for the tram network, PB was required, during the requirements definition phase, to undertake sufficient surveys and investigations, necessary to inform the design of the ETN. Although the SDS contract listed the type of surveys to be undertaken and included ground-penetrating radar, ground investigation and geotechnical surveys as well as a study of Network Rail assets to prepare accurate engineering drawings to be included in Network Rail agreements, the list was not exhaustive [ibid, page 0084, Schedule 1, paragraph 2.3.3]. In Chapter 8 (Utilities) I refer to evidence concerning inadequate ground investigation and the late provision of survey information. Mr Reynolds, Director of Infrastructure for PB between 2004 and 2007 and thereafter Director responsible for Light Rail Major Projects including the ETN, and Mr Chandler, Project Manager of PB for the design of the ETN, also accepted that there had been issues with inadequate ground investigation and the late provision of survey information on the part of PB, although they attributed such difficulties to access problems in respect of sections of the route in Princes Street and along parts of the Network Rail corridor (see paragraph 6.133 below).

6.8 PB was responsible (at its own expense) for obtaining all approvals and consents required for the construction, installation, commissioning, completion and opening of the ETN [ibid, page 0029, paragraph 5.1]. While this obligation included approvals required from City of Edinburgh Council (“CEC”) (acting as both planning authority and roads authority), it was of much wider application and included approvals and consents from affected landowners as well as Network Rail mentioned in paragraph 6.7 above. If the design deliverables produced by PB did not fulfil the needs of any approval body PB was required, at its own expense, to amend the design in order to meet the needs of the approval body [ibid, page 0028, clause 4.8].

6.9 Mr Reynolds gave evidence to the effect that normally there is “a heavy responsibility on the designer for securing approvals and consents” and that it was not unusual, at the time of the SDS contract, for designers to obtain approvals and consents. However, over time, there had been more recognition that that was a joint responsibility (i.e. between the client and the designer) [PHT00000019, pages 1–2]. One can see why that would be so. Regardless of any contractual obligation on a designer to obtain consents and approvals, that would work in practice only if there were a collaborative approach by all parties to ensure that the designer was able to modify the design to satisfy the requirements of the approval body. That is particularly the case where in the course of a project the requirements of an approval body change. In that event a designer, who had sole responsibility for obtaining the necessary consents or approvals, would require to amend the design to satisfy the approval body. Without the support of the client for such modification, the designer might be unable to obtain the necessary consents or approvals. Where, as in this case, it was necessary to obtain the approval and consent of adjacent landowners such as Forth Ports, Network Rail, Royal Bank of Scotland and Edinburgh Airport, the support of tie and CEC and their intervention with these third parties was essential to obtaining such approval and consent within a reasonable timescale.

6.10 Even if that support were forthcoming, the burden of the cost of such design change would fall on the designer where, as in this case, the designer was contractually bound to amend the design at its own expense. Where the amendment was occasioned by a change in the needs of the approval body from its requirements when the design was prepared initially one can understand the sense of grievance that the designer might experience. This is not an academic matter because Mr Reynolds explained that this had occurred in this case and for that reason at novation PB had succeeded in changing its obligation to fund design changes in that situation [ibid, page 2].

6.11 In the case of the project the required collaboration appears to have been lacking or, at least, ineffective. For example, Mr Chandler gave evidence that:

“TIE interpreted this [PB’s responsibility for obtaining all approvals and consents at its own expense] as an open ended obligation to continue to deliver design iterations until all those third parties were content and SDS had secured their approval.” [TRI00000027_C, page 0025, paragraph 87.]

6.12 This resulted in delay, which PB reported to tie. Without tie’s direction and collaboration with PB and its intervention with third-party stakeholders, PB was powerless to resolve the issues that had been raised by third parties. Mr Chandler explained PB’s difficulty in this respect as follows:

“The difficulty was that although SDS had the obligation through the contract to secure their approval, we could not really force a decision to effect that approval. So SDS were just left in a loop of providing iterations of proposals for design without having the power to force agreement with the third parties.” [ibid, page 0031, paragraph 114.]

6.13 In any project the consequence of delay is additional expense, and it is in everyone’s interests to seek to avoid that. Even where the obligation to obtain the approval of third parties rests solely with the designer, the client has a clear interest to assist the designer in obtaining that consent but it appears that tie did not appreciate that or, if it did, failed to act collaboratively with PB to achieve an early resolution of third-party objections to the design.

6.14 In relation to the design for the utilities diversions along the tram route, the SDS contract stated that PB was to “provide assistance to tie with the management of an advanced utilities diversion programme”, which was to include “assessing the need for and acquiring relevant data relating to the presence and location of all buried and above ground utilities” and “undertaking critical design and developing a strategy for all utilities diversions to minimise diversion requirements and out-turn costs” [CEC00839054, page 0091, Schedule 1, paragraph 3.2]. Although “critical design” was not defined, it clearly had a different meaning from design generally. In Chapter 8 (Utilities), indeed, this difference was recognised in practice to some extent because the reference to PB’s undertaking “critical” utilities design resulted in its undertaking the more complex utilities design, while standard, or routine, utilities design was to be undertaken by the utilities companies themselves, in relation to their own apparatus and connections. I will consider the issue of problems associated with the diversion of utilities in Chapter 8 (Utilities).

Programme

6.15 The programme included in the SDS contract was already a number of months out of date by the time that the SDS contract was signed [ibid, pages 0248–0261, Schedule 4]. For example, in relation to line 2 (from Newbridge to St Andrew Square), the programme indicated that work on outline design would start on 27 April 2005 and finish on 28 February 2007 [ibid, page 0253, Schedule 4]. Such a start date was clearly already impossible by the date of signature of the contract on 19 September 2005.

6.16 In addition, the contract included a programme phasing structure that indicated that preliminary design was to be approved for certain sections by 30 November 2005, and that detailed design was to be approved for those sections by 30 March 2006 [ibid, page 0112, Schedule 1, appendix 2] or by 30 May 2006 [ibid, page 0111]. Again, those timescales were out of date, and so were clearly unlikely to be achieved, by the time that the SDS contract was signed. Indeed, the programme phasing structure indicated that detailed design for all of phase 1a of the tram line was to be approved by 30 September 2006 (with the exception of the detailed design for Leith Depot, which was to be approved by 30 November 2006), which, again, was no longer realistic or achievable at the date of signature of the SDS contract.

6.17 The reason for the programme being out of date when the SDS contract was signed appears to have been a delay in entering into that contract and a failure to update the design programme to reflect that delay. No explanation was provided to the Inquiry as to why the design programme in the SDS contract was not updated to reflect the delay in its award. I consider that it is obvious that the design programme ought to have been updated before the SDS contract was entered into, so that all parties had an up-to-date and realistic programme that they could work to, and against which any delays could be tracked and reported.

6.18 After the SDS contract was signed it appears that tie and PB agreed that the deliverables for the requirements definition phase would be produced by the end of December 2005, and that those for the preliminary design phase would be produced by the end of June 2006.

6.19 The SDS contract further provided that PB would update and amend the design programme within 30 days of the signature of the contract and thereafter maintain, update and amend it in accordance with specified requirements. Any updates or amendments had to be approved by tie [ibid, page 0030, paragraph 7.1.2]. While revised design programmes were regularly produced by PB and sent to tie, it appears that these revised or amended programmes (which all showed slippage and delay) were neither approved nor rejected by tie. This was confirmed by Ailsa McGregor, who explained that when she joined tie in August 2006 as Project Manager for the SDS contract the original programme had slipped by three months due to delays in the procurement process. Although she had been advised that the programme had been re-baselined in April 2006 her understanding was that this had not been formally agreed with tie and the status of the programme was unclear [TRI00000250, page 0043]. The failure of tie to respond formally to the proposed revised design programmes is an illustration of tie’s failure to manage the SDS contract.

6.20 The SDS contract also required PB to adhere to the master project programme prepared by tie and to ensure that any updates or amendments to the design programme were coincident to, and aligned with, tie’s master project programme [CEC00839054, page 0030, paragraph 7.1.1 and page 0095, Schedule 1, paragraph 4.1.2]. It appears, however, that tie failed regularly to produce, update and distribute a master project programme. For example, PB’s claims document dated 31 May 2007 stated:

“tie is obliged to issue the Master Project Programme which shows the programming interfaces for all Tram Network contracts. PB has only been issued with one version of the Master Programme, (dated 19 February 2007), and this has impacted resource planning through the resulting lack of clarity on project overall requirements.” [CEC02085580, pages 0007–0008.]

6.21 Ms Clark, tie’s Programme Director, gave evidence that she was not able to dispute the evidence from PB witnesses that PB did not receive copies of the master project programme to enable it to plan its works, and that she did not recall that programme being sent to PB [PHT00000025, page 113]. This is another indication of tie’s management failure in the context of the SDS contract.

Payment

6.22 PB was entitled to payment under the SDS contract once milestones, or sub-milestones, were reached [CEC00839054, page 0041, paragraph 11]. The anticipated total contract value was £23,547,079 [ibid, page 0115, Schedule 3]. The SDS contract did not, however, provide for financial incentives if the design was delivered early, nor did it provide for financial penalties if it was delivered late.

SDS novation

6.23 As was noted in paragraph 6.1 above, PB was obliged to enter into a novation agreement with Infraco if, and at the time, requested by tie. The form of the novation agreement was set out in schedule 8 to the SDS contract [ibid, page 0070, paragraph 29.1 and page 281].

Client representative

6.24 The SDS contract provided for tie to appoint a client representative, who was to be PB’s primary point of contact with tie and responsible for the day-to-day supervision of the services to be provided by PB [ibid, pages 0039–0040, paragraph 10.1]. In terms of clause 10.8 PB had an equivalent obligation to appoint a “SDS Provider’s Representative” to be the principal point of contact with the client representative. These arrangements were conducive to the effective and efficient management of the SDS contract. Nevertheless, clause 10.4 recognised that there may be periods when nobody was performing the functions of the client representative, such as before any appointment was made or during the illness or incapacity of the client representative. In that event tie would perform the duties of the client representative. On the other hand, PB was obliged to nominate a deputy to its representative to act when the representative was unable to exercise his functions [ibid, page 0041, paragraph 10.10].

6.25 I am of the view that when considered as a whole, the provisions relating to the appointment of representatives recognised the obvious advantage of such appointments for the efficient management of the SDS contract. Although provision was made for tie assuming the responsibilities of the client representative prior to an appointment being made, it seems unlikely that parties anticipated that no appointment would be made for approximately a year after the signature of the contract. Despite this, it does not appear that tie had appointed a client representative before the appointment of Ms McGregor in August 2006 or, that if one had been appointed, who that individual was or what, if any, supervision they exercised over the services provided by PB. That is also consistent with PB’s progress reports for May and August 2006, which noted the need for tie to inform PB of the name of tie’s client representative (described as tie’s contract representative in the progress reports) [CEC01684827; CEC01359145].

6.26 Furthermore, there was little evidence before the Inquiry of tie’s having exercised supervision or oversight of the SDS contract or the services being provided by PB before Ms McGregor’s appointment. That was recognised in, for example, tie’s progress report dated 6 October to the Tram Project Board (“TPB”) on 23 October 2006, which noted: “[w]e recognise that we have to control and manage the contract more effectively” [CEC01355258, page 0009]. Mr Crosse, tie’s Tram Project Director (“TPD”) between January 2007 and March 2008, concluded from discussions with his predecessor, Mr Harper, and with work stream leaders, that SDS leadership was not very strong. More significantly he concluded that tie was not managing SDS and the contractual relationship between tie and SDS particularly well. There was nobody qualified within tie to perform the role of Chief Engineer and tie was often late in delivering information to SDS that it required to complete designs. In short, technical leadership was poor on both sides and collaboration was non-existent [PHT00000021, pages 34–36].

6.27 That is also consistent with the evidence to the Inquiry that tie initially appears to have thought that it would have a minimal role in the design process, simply relying on the obligation on the SDS provider to produce design and obtain approvals in accordance with the programme, with minimal involvement by tie. Ms Craggs considered that tie did not have the experience of managing such a contract and failed to anticipate the level of management that was required to ensure that SDS was fulfilling its obligations [PHT00000016, pages 100–101]. I accept that evidence.

Requirements definition phase

6.28 During the requirements definition phase, PB was required to produce a set of functional requirements specifications (i.e. the functional and operational requirements for the tram scheme), which would provide a baseline from which the preliminary design could be developed. A number of surveys were also to be undertaken by PB during that phase, to inform the design and technical specifications [CEC00839054, page 0084, Schedule 1, paragraph 2.3.3].

6.29 While PB delivered the requirements definition documents on time on 19 December 2005, within the agreed 13-week period for their production, there were issues concerning the quality and level of detail of some of the deliverables, which required to be addressed during the preliminary design phase (i.e. between January and June 2006). Mr Chandler, who replaced PB’s existing Project Manager for the project in February 2006, considered that the delay in the signature of the SDS contract reduced the time available for the requirements definition phase and that there had been a rush to complete PB’s submission within the restricted timescale. The division of the responsibilities around the PB team for the project was not very clear, and the programme produced by PB was overly complicated [PHT00000020, page 5].

6.30 In an internal PB “lessons learned” document produced in August 2007, Mr Reynolds commented:

“The client enforced an unreasonably short period of time for the requirements definition phase and this was signed up to by PB. There was insufficient time for orderly mobilisation and quality and timeliness of deliverables suffered. As a consequence PB’s reputation suffered and the client’s perception of PB’s poor performance carried through into preliminary and detailed design.” [PBH00028567; PBH00028568, pages 0001–0002.]

6.31 That document also recognised failings on the part of PB. The person in charge of the project for PB was ineffective. He “failed to educate the client as to how the scheme would be engineered and was unable to work with the client to agree a workable delivery plan”. This was the first contract in which PB had used “multi-office design delivery” but more significantly PB had failed to undertake a proper risk assessment for the project. Had it done so it would have foreseen “CEC modus operandii (sic)”. CEC’s approach and tie’s inability to control CEC’s aspirations were considered to be the primary cause of design slippage.

6.32 While there was evidence that the shortcomings in the requirements definition deliverables were addressed during the preliminary design phase, the evidence to the Inquiry was that, in general, it would have been better to have stopped, and reached agreement, at the end of each stage of design before moving on to the next stage. By proceeding in that manner there would have been an agreed, and fixed, baseline from which to develop the next phase of design, thereby reducing the risk of previous design being re-visited and changed. In that regard Mr Harries, of Transdev Edinburgh Tram Limited (“Transdev”), gave evidence that

“normally the design process is that you develop an initial design and then you develop into a preliminary design and then it’s developed into a detailed design, and then you go out and build it. At each of the stages it is reviewed by those people who need to review it, so that you have a series of agreed stages in the development of the design, and that process reduces the risk of having to do a lot of rework.” [PHT00000016, pages 20–21.]

6.33 One of the difficulties with the production of a design that was acceptable to CEC as the planning and roads approvals authority and as the ultimate client was the lack of engagement of CEC with the designer at an early stage. While there was before the Inquiry evidence of some engagement by PB with CEC during the requirements definition phase, in short, the weight of evidence was that greater engagement with CEC at an earlier stage would have been helpful in clarifying its wishes and requirements before the design was developed further.

6.34 By way of example, one of the difficulties for the SDS provider was to ensure that the design of the project reflected the city’s status as a World Heritage Site. That was dependent on subjective judgements and appears to have led to uncertainty as to what, exactly, was required by CEC in its dual role as client and approvals authority. The problem is, perhaps, illustrated by the requirement in the SDS contract that design for the on-street section between Haymarket and Ocean Terminal via Princes Street should:

“provide a look and feel that is at one with its surroundings whilst not detracting from the design elsewhere on the Edinburgh Tram Network” [CEC00839054, page 0088, Schedule 1, paragraph 2.7.1.1].

6.35 While there is nothing wrong with such a goal or aspiration in itself and such an aspirational statement is not uncommon in construction or design contracts, it was of doubtful value in this case. In a situation in which timing was important and the requirement for consent from CEC sat alongside a number of contracts and considerations, it would have been of assistance to have a statement of what CEC sought in more practical detail.

6.36 Although, around December 2005, CEC did produce a Tram Design Manual, which gave some guidance on design principles, that guidance was of a very general nature [CEC00069887]. It was not until April 2008 that CEC produced a draft Tram Public Realm Design Workbook [PBH00018590; CEC02086917; CEC02086918; CEC02086920–CEC02086934],[13] which gave more detailed guidance on matters such as surfacing, materials and construction details. A letter dated 10 April 2008 from Mr Henderson, Head of Planning and Strategy, CEC, to Mr Bell, tie’s TPD, enclosed a copy of the draft Workbook. The purpose of the letter was “to suggest a way of ensuring that the designs for the Tram project fit with the Council’s wider aspirations for public realm”. Although the Workbook was a work in progress position document, Mr Henderson expected that it would “assist in developing the details of the Prior Approval Designs and Technical Approvals that are now coming forward for the City Centre” [PBH00018590]. This guidance was intended to supplement the guidance in the Tram Design Manual [CEC00069887] and the Edinburgh Standards for Streets [CEC00669586].

6.37 Mr Glazebrook, Engineering Services Director of tie between 2007 and 2011, gave evidence that he had not seen the draft Tram Public Realm Design Workbook [PBH00018590; CEC02086917; CEC02086918; CEC02086920–CEC02086934]* although it had been sent to Mr Bell. Although Mr Glazebrook considered that its production was too late and ought to have included guidance on other matters of detail required by CEC, it is surprising that he was not included in its circulation and reflects adversely on the management culture within tie. He considered that had that more detailed guidance been issued earlier, it would have assisted the designers in producing design that met CEC’s requirements, which, in turn, would have enabled design, approvals and consents to have progressed more quickly. Moreover this guidance should have been available to the designers at the outset of the SDS contract, not in 2008 [PHT00000014, pages 142–144].

6.38 I consider that it was particularly important that such guidance should have been given at an early stage in the project, in view of its unique features: the facts that a substantial portion of the tram line would run through a UNESCO World Heritage Site and that it would be the first such line to be built in Edinburgh in recent memory, with the result that its design principles would require to be developed “from scratch”, there being no existing scheme to look to for guidance. On any view, CEC ought to have produced sufficient detailed design guidelines before the SDS contract between tie and PB was signed to enable PB to take them into account when designing the tram network. Had that occurred it is likely that PB would have received the necessary consents and approvals from CEC sooner than actually occurred. CEC’s failure to do so contributed to the delays in the design of the project.

Preliminary design phase

January–June 2006

6.39 PB worked on the preliminary design between January and June 2006, with the preliminary design deliverables being sent to tie at the end of June 2006, within the agreed time period. In producing the preliminary design deliverables, PB took account of comments on, and sought to address deficiencies in, the requirements definition deliverables.

6.40 In late 2005, after design work had started following the signature of the SDS contract, various changes had been made to the design requirements for the tram scheme as a result of the parliamentary process leading to the enactment of the Tram Acts in April and May 2006. PB had no involvement in the parliamentary process and was unaware of these changes before it commenced work on design. Ms Craggs, a solicitor with Dundas & Wilson, advised CEC and tie during the parliamentary phase of the project and between March 2006 and March 2007 she was seconded to tie on a full-time basis, as Director of Design, Consents and Approvals. She gave evidence that, in the summer and autumn of 2005, the Scottish Parliament was considering various proposed amendments to the alignment of the route and did not conclude its consideration of that issue until Christmas 2005. Significant changes were made to the original plans and sections submitted to the Scottish Parliament, particularly those for Haymarket Yards, Newhaven and the Gyle. At Haymarket Yards the route changed completely. The changes also included changes to the horizontal and vertical limits of deviation. Thus the baseline from which PB had to prepare designs changed significantly without tie advising it of the changes. Ms Craggs doubted the prudence of starting the preliminary design phase until there was certainty about the route and the limits of deviation [PHT00000016, pages 130–134].

6.41 The failure to notify PB of the changes in December 2005 meant that PB was preparing the preliminary design on the basis of the original drawings submitted to the Scottish Parliament, which were no longer the correct baseline from which to develop that design. In March or April 2006 when Ms Craggs was discussing the “virtual route” at a meeting with PB shortly after her secondment to tie in March 2006 she noted that tie had failed to advise PB of the changes to the baseline. Mr Dolan, of PB, explained the effect of the late notification of these changes to PB as follows:

“We were two thirds of the way through our PD [preliminary design]. There were changes … We took it on board for the last two months of our preliminary design stage as best we could.” [PHT00000019, page 207.]

6.42 Any changes from the parliamentary process that were not reflected in the preliminary design were to be taken forward into the detailed design [ibid; see also Mr Chandler PHT00000020, pages 22–23].

6.43 The changes to the baseline from which PB had to prepare designs and the failure of tie to keep PB informed of such changes meant that PB had to carry forward elements of preliminary design into the detailed design phase. This prevented the orderly progression of design mentioned by Mr Harries in paragraph 6.32 above, and introduced the risk of tie or CEC insisting upon changes to the preliminary design during the detailed design phase. tie’s failure to inform PB of the changes when they arose also reflects upon its poor management of the project. Although Ms Craggs doubted the prudence of starting the preliminary design phase until there was certainty about the route and the limits of deviation, she thought that PB could have undertaken the requirements definition phase before such certainty existed. I disagree with that approach. It is not uncommon for changes to be made to a scheme during the passage of private legislation to accommodate objections to the scheme. In these circumstances it would have been prudent to await the necessary certainty about the route that was to be designed before the signature of the SDS contract. This would not have prevented the terms of that contract being negotiated and agreed subject to finalisation of the baseline drawings and would have allowed PB to discuss with CEC its design requirements before signature of the contract to reduce the scope for the disagreement that ultimately arose.

July 2006 onwards

6.44 Following PB’s delivery to tie of the preliminary design at the end of June 2006 tie had 20 working days within which to review and accept or reject it [CEC00839054, page 0027, paragraph 4.1 and pages 0290–0294, Schedule 9]. tie did not respond to the preliminary design within that timescale. Instead it participated in the protracted process mentioned below.

6.45 At the same time, CEC received a copy of the preliminary design for review. CEC had had little previous involvement in the design process and saw this as its opportunity to have an input into design. In particular, a number of design workshops (or “design charrettes”) took place, which resulted in further, and alternative, design options being explored. Mr Fraser, CEC’s Tram Co-ordinator between June 2007 and September 2009 with the primary role of processing roads and planning consents and approvals, gave evidence that the charrette process

“was the first significant opportunity for CEC to directly influence the quality of the interaction of the tram within the urban landscape” [TRI00000096_C, page 0011, answer 7(1)].

6.46 Charrettes were held in respect of various on-street locations (Haymarket, Shandwick Place, Princes Street, St Andrew Square, Picardy Place, Leith Walk, and the Foot of the Walk) and in respect of various structures on the off-street section (Edinburgh Park viaduct, Carrick Knowe bridge, Coltbridge viaduct and Craigleith Drive bridge).

6.47 In addition to the charrettes, a design approval panel was set up, with representation from CEC. Planning summits were held and CEC staff were co-located to tie’s offices, all with a view to ascertaining and agreeing CEC’s design requirements. It is clear from the evidence that CEC staff ought to have been involved in design issues from the start of the project and throughout the different phases including the initial phase of design deliverables; if that had occurred it might have avoided many of the problems with design approval that subsequently occurred. CEC’s involvement in design issues, including staff co-location in tie’s offices, came too late in the process [Mr Chandler, of PB PHT00000020, pages 21–22; Mr Harper, tie’s TPD at that time TRI00000043_C, pages 0021–0022, paragraph 72].

6.48 The late involvement of CEC officials in design issues, including the introduction of the charrettes and the design panel, resulted in options being reconsidered that had already been rejected and in issues being raised that ought to have been addressed and resolved before the award of the SDS contract, or during the design requirements phase at the very latest. The SDS contract did not address the need for the early involvement of CEC officials in the design process. It ought to have been apparent to tie that CEC, as the ultimate client and the planning and roads authority, had a significant interest in the design of the project. Its input into the design process was essential and tie and PB ought to have engaged with CEC much earlier than they did and, in any event, at least prior to the commencement of work on the preliminary design. I agree with the evidence of Ms Craggs when she stated:

“I think that tie had not really thought about how the various inputs from organisations/stakeholders would be co-ordinated … tie had not properly thought through how CEC’s input would work, nor had SDS. I think that was the biggest problem … I think naively everyone thought that preliminary design would be signed off with very little discussion or additional work requiring to be done on it.” [TRI00000029, pages 0040–0041, paragraph 98.]

6.49 Mr Reynolds considered that tie lacked the necessary experience of a major construction project to manage the programme and, in particular, to challenge the stakeholder requests for change as a result of requirements that were made after the preliminary design had been submitted to it [TRI00000124_C, pages 0041–0042, paragraphs 137–138]. tie’s mismanagement of the SDS contract is also illustrated by PB’s receiving requests to prioritise different items of design, at different times, from different teams within tie in a manner that lacked co-ordination, resulting in an inefficient process for the production of design. For example, in November 2006, without consulting PB, tie’s Infraco procurement team re-prioritised the SDS programme to accommodate the appointment process without apparently appreciating the adverse effect that would have on the delivery of the SDS programme overall [Ms McGregor TRI00000250, page 0084]. This practice was still evident in February 2007 when Ms Craggs commented upon it in an email to Mr Crosse in the context of SDS programme/priorities and work to award the Infraco contract. As was observed by Ms Craggs, such an approach could prejudice the overall programme and affect other work streams [CEC01826622].

6.50 The extent of the problems occasioned by the late involvement of CEC and the introduction of charrettes and the design panel at this stage in the process is illustrated by the evidence of Mr Chandler to the following effect.

“Decisions that SDS thought had already been made were open for discussion. SDS thought we were producing a preliminary design developing the outline design that had been through a lengthy parliamentary process. What we had not anticipated at the end of the preliminary design was the level of potential change that was to follow. Even very basic decisions about how many tram-stops there were going to be were questioned and the route of the tram itself. Even the option of relocating the depot to Leith was considered. That optioneering had been done several years before and discounted. The impact on SDS was catastrophic … There were very lengthy delays and … progress … suddenly stalled … After submitting the preliminary design, for it all to unravel and to go back almost to optioneering around the route and what the route should look like and how the tram should progress is very unusual.” [TRI00000027_C, pages 0044 and 0066, paragraphs 168–171 and 259.]

6.51 The consideration given to further design options in the second half of 2006 meant that PB was unable to progress the detailed design stage meaningfully. Clearly, that stage could be developed only once tie and CEC confirmed their preferred design options. In addition, detailed design for roads and junctions could commence only once traffic modelling had been undertaken – and that could be done only once the preliminary design for roads and junctions had been agreed. In her September report tie’s SDS Project Manager, Ms McGregor, noted that the decision to adopt a review process that was inconsistent with the SDS contract had had a seriously adverse effect on the critical programme dates and prevented PB from proceeding to detailed design. She identified the key issues that were affecting progress as:

- “Charette [sic] Changes and changes TEL/CEC approval required; quantum agreed in principle

- Programme and reporting

- Deliverables (not clearly defined)

- PD review process” [TIE00073020].

6.52 Delays in finalising design also arose due to the need to take account of the wishes and requirements of a number of third parties at various locations along the route – in particular at: Leith (Forth Ports); Picardy Place (in relation to a proposed hotel development at the Picardy Place roundabout); Haymarket; the Scottish Rugby Union (“SRU”) (Murrayfield); the Royal Bank of Scotland tram stop; and Edinburgh Airport. The wishes and requirements of Network Rail also required to be taken into account in respect of the sections of the tram line that would run alongside the railway line.

6.53 Until the wishes and requirements of CEC and third parties were resolved, the design of the network could not be finalised. For example, CEC’s wishes in respect of the junction at Picardy Place were influenced by the proposed development at St James Centre and included the possible location of a hotel on the site of the roundabout at that junction. Until the land uses at that location were finalised it was not possible to have a concluded design for that junction. In passing I note that CEC undertook a further consultation exercise about that junction in connection with the tram extension from York Place to Newhaven following the conclusion of the evidence at the Inquiry and after work on the redevelopment of St James Centre had commenced. Had a similar exercise been undertaken and a decision reached about land uses in that location before the SDS contract was signed, changes in design there and the consequent delay and expense would have been avoided.

6.54 Moreover, as explained by Mr Chandler, the introduction of a tram system into the city of Edinburgh was extremely complex. The alignment of the track was a critical element of the design as it affected the amount of disruption due to associated highway works. There were extremely tight tolerances for the alignment of the track in relation to adjacent structures or even the tram stops themselves. What appeared to be a relatively minor change to the design (for example, by changing a kerb alignment or by moving a tram stop by a few metres) could have a significant impact upon other parts of the tram infrastructure and on the existing infrastructure around Edinburgh. Such interdependencies meant that the design team had to consider the implications of any change for the design as a whole and had to make changes to other design details that then required further approval.

6.55 By late 2006, it was clear that the design programme had become considerably delayed. A “dashboard” report for December 2006 noted that 28.3 per cent of the detailed design had been undertaken, against the 71.9 per cent that had been programmed for that stage using the baseline figures for April 2006 [TIE00040946; TIE00040947].

6.56 In December 2006, Scott Wilson Railways (which was tie’s Technical Support Services (“TSS”) Provider) produced a Preliminary Design Review Report [PBH00026782]. It noted that, by the middle of October 2006, it had become clear that the overall review process “was in somewhat disarray [sic] and required to be closed out with SDS” [ibid, page 0007]. The review noted that the engineering aspects of the project seemed generally to be on course, with the notable exception of the structures. Decisions were outstanding on certain design aspects, for which PB could not be held wholly responsible. The overall conclusion in the report was that “the bulk of the Preliminary Design submission is now either acceptable or acceptable given the responses from SDS” [ibid, page 0005]. Various ongoing, outstanding and unresolved issues would be addressed during the detailed design phase.

6.57 It can be seen, therefore, that, again, rather than agreeing one stage of design (i.e. preliminary design) before moving on to the next (i.e. detailed design), it was agreed that unresolved design issues would be carried forward to, and addressed in, the next design phase. However, on this occasion the preliminary design had been based upon the designer’s reasonable assumption that CEC and tie were happy with the concept design, the route, the number of tram stops and the outline layout of the traffic junctions that had been resolved during the parliamentary process. Many of the unresolved preliminary design issues arose because of the proposed changes to that baseline. It would have been prudent for PB to insist upon resolution of these proposed changes to enable it to complete the preliminary design before proceeding to detailed design. Mr Chandler explained that PB ideally would have “liked to have a very clear set of guidance notes almost on how the design should be completed” [PHT00000020, page 35]. That guidance was not provided at that time and PB succumbed to pressure to adhere to the programme despite the outstanding critical decisions.

6.58 The draft Final Business Case (“FBC”) for the project was presented for approval to members of CEC on 21 December 2006 [CEC01821403]. In discussing the FBC here, I may appear to repeat observations made in Chapter 5 (Procurement Strategy). While acknowledging that such repetition may occur, I consider making these observations to be worthwhile in the different contexts under examination. It set out the intention that the novation of the SDS Contract to Infraco would transfer responsibility for the design and its associated risks to the Infraco without incurring the risk premium normally associated with bidders having to undertake all the design work after contract award. Moreover, it not only anticipated that design to detailed design would be 100 per cent complete when the Infraco contract was signed but also noted that tie was seeking to complete the key elements of the detailed design prior to the selection of the successful lnfraco bidder in summer 2007 to enable lnfraco bidders to firm up their bids based on the emerging detailed design. This would reduce the scope and design risk allowances that bidders would otherwise include [ibid, page 0085, paragraphs 7.50 and 7.53]. The draft FBC included a programme summary, showing that detailed design for phase 1a was due to be completed and all approvals and consents to be obtained by 4 September 2007, with the Infraco contract being awarded in October 2007 [ibid, pages 0166–0167]. The programme had very little float and was based upon “the assumption of ‘right first time and on-time’ delivery of activities”, particularly SDS design work [ibid, page 0164, paragraph 11.3]. As will be mentioned in paragraph 13.12 of Chapter 13 (CEC: Events during 2006 and 2007), the draft FBC, and the report to CEC on 21 December 2006, contained no reference to the serious difficulties and delays that had arisen on the design programme.

6.59 Mr Crosse, of tie, considered that the reference in the draft FBC to design being 100 per cent complete was an “idealised concept”, which:

“possibly led people to expect, possibly out of ignorance, that it would be a pile of drawings and specifications tied up in a bow, perfect. You don’t need to do any more. It was never going to be that.” [PHT00000021, page 45.]

Here, I may appear to repeat observations made in paragraph 5.83 above and 10.8 below. While acknowledging such repetition, I consider making these observations to be worthwhile in the different contexts under examination.

6.60 He gave evidence that design would always require to change after the award of the Infraco contract, that it was not possible for design to be 100 per cent complete when the contract was awarded and that it is not possible to eradicate the premium charged by the infrastructure contractor for accepting design risk. Although both he and the management team in tie were aware that design would not be 100 per cent complete when the Infraco contract was awarded, he was unaware whether that had been communicated to officials or councillors in CEC.

6.61 While I accept that the statement that the design would be 100 per cent complete when the Infraco contract was awarded may be misinterpreted in the manner suggested by Mr Crosse in paragraphs 6.59 and 6.60 above, there can be no doubt that a fundamental part of tie’s procurement strategy was to develop the detailed design to the stage of obtaining the necessary consents and approvals prior to the award of the Infraco contract. The purpose of that part of the strategy was to minimise the risk premium that the successful Infraco bidder would include for design risk. That does not mean that anyone anticipated there “would be a pile of drawings and specifications tied up in a bow” which required no further work prior to construction. As I have indicated in paragraph 6.1 above, Infraco would require to complete the detailed design by incorporating the components and systems that had formed part of its bid. When the draft FBC is considered as a whole it is clear that, in accordance with the procurement strategy, the intention was to develop the design to such an extent that the successful Infraco bidder would have a detailed design that had the approval of the relevant statutory bodies and interested third parties and that it could adjust as necessary at its own risk prior to constructing the tram network. The programme mentioned in paragraph 6.58 above was intended to achieve that objective. Further, tie aspired to the completion of key elements of the detailed design prior to the selection of the successful lnfraco bidder in summer 2007 to enable lnfraco bidders to firm up their bids based on the emerging detailed design.

6.62 Having regard to the nature and extent of the changes to the preliminary design mentioned above, I have concluded that in late 2006 it was overly optimistic for tie to report that design would be completed by September 2007 or that when the Infraco contract was awarded detailed design would be 100 per cent complete in the sense mentioned in paragraph 6.61. Support for that conclusion can be found in the evidence of Ms McGregor, of tie, and Mr Reynolds, of PB. Ms McGregor considered that the statements about design in the draft FBC were “very optimistic”, given “the high number of critical design and charrettes issues affecting large parts of the route at that time and the programme delays” [TRI00000250, page 0082]. Mr Reynolds gave evidence that when he became PB’s Project Director in February 2007 “it was already clear that there was a very high risk that that September date for completion of detailed design wouldn’t be met” [PHT00000019, page 19]. As will be seen, these concerns were justified, although I suspect that neither of these witnesses anticipated the extent of the delay that would ensue. Design was still incomplete and consents and approvals for significant parts of the design had not been obtained when the Infraco contract was signed in May 2008.

Detailed design phase

6.63 By the beginning of 2007, a large number of critical design issues had arisen that prevented detailed design from being progressed meaningfully. In an email dated 18 January 2007, Ms McGregor expressed her concern that “we do not deal with the issues and just pretend they do not exist and are ‘somebody else’s responsibility’” [CEC01811518].

6.64 In January 2007, Mr Crosse was appointed tie’s TPD. The minutes of a meeting of the Design, Procurement and Delivery (“DPD”) Sub-Committee held on 16 January 2007 noted:

“SDS progress – Concerns were raised about the practicalities of expectations and the changing priorities by different stakeholders on the delivery of SDS milestones. Late inputs from tie and CEC into the design process further aggravated the situation.” [CEC01766256, page 0003, paragraph 2.4.3.]

6.65 Mr Crosse was to provide a “get well” plan for design, taking account of the concerns discussed at the meeting.

6.66 In January 2007, tie also instructed Mr Crawley, an engineering consultant with experience of tram and light railway systems, to carry out a high-level review of the design review process. Mr Crawley was told that the project was in trouble and that it was hoped that a review might help to identify both the issues that were causing the difficulties and also possible solutions to them. He interviewed a number of individuals and produced a report [CEC01811257], which noted a number of serious concerns on the part of interviewees, including that the programme would not be met if the current design review arrangements continued as well as the need to improve change control.

6.67 Mr Crawley gave evidence that while his review concerned the design review process rather than the project overall, it was impossible to ignore wider issues that had emerged that were not specifically confined to the design review process.

“The phrases which kept on emerging were poor leadership, not feeling like one team and everybody knowing that in their opinion the project was too late to be delivered in anything like the original programme and to budget.” [PHT00000014, page 16.]

6.68 For his part, Mr Crosse gave evidence that when he joined the project he formed the view that PB leadership was not very strong. He also considered that tie was not managing PB or the SDS contract very well and that there was a need for it to appoint a chief engineer to take overall responsibility for the design process and make decisions on technical issues. It was also clear to him that tie and CEC needed to work more closely together in the design development. He also considered that collaboration between tie and PB was non-existent and that a collaborative approach required to be introduced [PHT00000021, pages 34–36]. He was of the view that the problems with design required to be addressed because design was on the critical path for the whole programme for the project. He agreed with the suggestion put to him by counsel to the Inquiry that design remained on the critical path and was a cause of concern, throughout 2007 [ibid, page 32].

6.69 As part of the remedial measures taken by tie, in February 2007 Mr Crawley was appointed as its Director of Engineering, Assurance and Approvals, with a view to providing leadership in engineering and design and trying to resolve the critical issues that were preventing design from being progressed. Mr Crawley shared his post with Mr Glazebrook, who was also appointed around that time (both worked for tie as consultants rather than employees). The extent of the design problems is illustrated by the evidence of Mr Crawley that within an hour of commencing his role at tie he learned that there were 79 major issues upon which PB required instructions from tie. An impasse had been reached. PB did not wish to assume the risk of proceeding with detailed design without receiving instructions from tie on the outstanding critical issues and suspended work pending receipt of instructions. The suspension of work on design extended between February and July 2007. Mr Crawley’s role included providing PB with instructions on the outstanding critical issues to resolve the impasse and he succeeded in reducing the number of issues to single digits by July 2007 [PHT00000014, page 19]. This is discussed in more detail in paragraphs 6.74–6.80 below.

6.70 PB also made changes to the leadership of its team at that time. In particular, in February 2007, Mr Reynolds, who was a senior executive of PB, sitting on its board, was appointed as its Project Director for the project. Mr Reynolds gave evidence that he was appointed to that role with a view to improving PB’s financial position and improving relations with tie. As regards PB’s financial position, Mr Reynolds explained that

“towards the end of 2006 … the project was … a problem as far as Parsons Brinckerhoff were concerned, because the monthly reporting on the financial performance was showing that the results were going in the wrong direction. The margins that were being delivered were reducing. We were looking at a seriously loss-making project.

“Certainly early 2007, it was number 2 on PB’s global list of problem projects. So it needed senior involvement to address that problem and come in and work with all concerned to recover the commercial position from PB’s point of view.” [PHT00000018, page 186.]

6.71 Shortly after their respective appointments Mr Crosse and Mr Reynolds gave a joint presentation to the DPD Sub-Committee on 13 February 2007 on Improving Design and Engineering [PBH00021285]. The slides for the presentation noted that the underlying issues arose from the following factors:

“- Project structure means tie doesn’t always face up to asset ownership responsibilities

– Project prone to gridlocks through indecision and poor co-operation of stakeholders

– Some tie resource weaknesses and with a lack of engineering leadership

– Overly ambitions [sic] programme, with a disconnect to outputs

– Variable quality and processes + inconsistent follow through

– Design programme inflexible – unable to satisfy everyone.” [ibid, page 0003.]

6.72 Moreover, on 22 February 2007, Mr Crawley chaired a meeting with a view to identifying an achievable and aligned programme for the project. As a result of that meeting, Mr Crosse proposed a five-month delay to the programmed date of financial close of the Infraco contract [PBH00021529, page 0001, paragraph 3].

6.73 Mr Reynolds was asked why the project was becoming a loss-making one for PB, and for his initial impressions about the project more generally, and he replied:

“The headline impression was that change control hadn’t been managed effectively, that the team here was bending over backwards trying to accommodate repeated change, but in trying to deliver the Parsons Brinckerhoff services had lost sight of the need to enforce rigorous commercial control on that change control process.

“So one of the first things I did very quickly was put in a proper change control regime which achieved two things. It highlighted to all parties the volume of change that we were experiencing, and it made sure there was better commercial assessment of the consequences of change.” [PHT00000018, page 187.]

6.74 Following his appointment, Mr Crawley, in conjunction with Mr Reynolds, introduced changes to the design process with a view to addressing the difficulties and delays that had occurred to date. In particular, a “critical issues” initiative was implemented, with a view to resolving approximately 80 critical issues that had built up and were preventing detailed design aspects from being progressed. Such issues were largely items of design on which confirmation was required from CEC and other stakeholders on which options they wished. Critical issues meetings were held weekly and were attended by representatives from tie, SDS, CEC and Transport Edinburgh Limited. In an email dated 23 March 2007, Mr Crawley explained:

“The consensus of view is that a decision, even if sub-optimal in the first instance, will allow for faster progress to be made through subsequent change control than delay for a ‘better’ decision.” [CEC01628233, page 0001.]

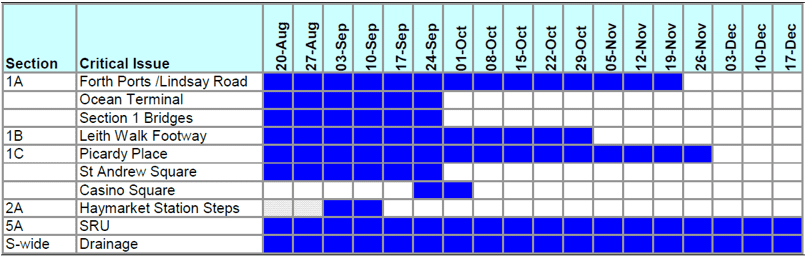

6.75 The scale of the problem concerning critical issues was highlighted in a claim for additional management and supervision services submitted by PB to tie in February 2008 that was settled by tie. The details of that claim are discussed in paragraph 6.125 below and it is sufficient to note at this stage that the settlement included £450,000 for additional management and supervision services provided by PB to tie after July 2007 which included additional costs incurred by PB relating to the resolution of a number of critical issues. Although there were about 80 critical issues to be resolved, the critical issues listed in Table 6.1 were the most significant. In addition, the claim relied upon revisions to the design of the project following the abandonment of the Edinburgh Airport Rail Link (“EARL”) which were not resolved until 16 October 2007 and the final solution at Balgreen Road that remained unresolved at the date of the claim because of lack of agreement about the height of the bridge there.

Source: SDS Contract Valuation dated 19 February 2008 by Parsons Brinckerhoff Limited [CEC00186740, page 0005]

6.76 A further change initiated by Mr Crawley and Mr Reynolds was that once the critical issues were resolved, and detailed design could progress, design was to be produced in self-assured design packages. Instead of tie instructing its technical advisers, TSS, to review and assure the design, PB would self-certify that the design complied with all relevant standards and requirements. In an email dated 26 April 2007 to Mr Reynolds, Mr Crawley explained:

“The overall concept is that you will deliver design ‘packages’ containing logically grouped design (in order to address interdependencies) and will add a covering statement which provides competent assurance that the design is fit for purpose.” [PBH00010843, page 0002.]

6.77 Between February and June 2007, almost all the critical issues were addressed, mainly by tie’s providing instructions to PB on how to proceed with design on those issues [see letter dated 26 June 2007 from Mr Glazebrook to Mr Reynolds, attaching a schedule of critical issues with instructions to enable design to be progressed, CEC00186740, page 0082, appendix 4]. In an email dated 29 June 2007 to Mr Crawley, which was copied to Mr Glazebrook and others, Mr Reynolds confirmed that PB was remobilising its design team in response to tie’s instructions to proceed. In a table attached to his letter dated 11 July 2007, Mr Reynolds set out PB’s response to tie’s instructions in relation to each of the critical issues [PBH00003595]. The table noted that while the instructions were sufficient to enable design to be developed in relation to many (but not all) of the issues, further information, discussion and agreement would be required before the design for some of the items could be completed.

6.78 Although, in summer 2007, tie issued instructions to PB in relation to most of the outstanding critical issues that enabled PB to recommence work on the detailed design of the project, it is clear from Mr Reynolds’ response mentioned in paragraph 6.77 and from PB’s claim mentioned in paragraph 6.75 that the critical issues were not completely resolved by that time. There is a distinction between tie issuing instructions on how to proceed and the resolution of a critical issue. As Mr Chandler explained, from July 2007 tie gave PB direction on how to proceed with the critical issues that had been frustrating progress with the design but that did not finally resolve these issues. As part of the design approvals and consents process it was still necessary for PB to work with various different stakeholders to obtain their approval of a design based upon tie’s instructions. As an example of continued issues after the summer of 2007 he explained that uncertainty around finalisation of the design for the junction at Picardy Place affected traffic modelling and the finalisation of other road junctions. Picardy Place was a central node which had the potential to impact on traffic flows across the city. He also referred to delays in finalising the design for Forth Ports, the Airport, and the Haymarket junction as further examples [PHT00000020, pages 29–31].

6.79 “Critical issues” that were the subject of instructions from tie in the summer of 2007 resurfaced to cause further delay. For example, an email dated 18 January 2008 from Mr Hickman, Programme Manager at tie, noted that Mr Crawley had advised him that there were various additional issues resulting from that morning’s critical issues meeting that would require to be incorporated in any design programme update [TIE00038271, page 0002]. In an internal PB email dated 21 January 2008 Mr Reynolds noted: “tie is completely disorganised and a number of very key issues are just being allowed to float.” He referred to the “fiasco” of the critical issues meeting on 18 January and his dismay that “so many of the matters discussed were the same as the issues that were on the table 6 months ago.” [PBH00015934].

6.80 In summary, the evidence before me was to the effect that detailed design was unable to be progressed meaningfully for a period of approximately one year, between July 2006 and July 2007, as a result of the consideration given to further design options, the failure to resolve various critical issues and the failure to give PB clear guidance and instructions on what tie, CEC and various third parties required. Moreover, it is apparent that critical issues remained outstanding in 2008 that compounded the delay of almost a year mentioned above and had an adverse effect upon the progress of detailed design. I accepted that evidence. It is self-evident that if such delay had not occurred the detailed design of the project would have been far more advanced at the date of the signature of the Infraco contract. In that situation it is probable that the design would have been sufficiently advanced to enable tie to achieve its procurement strategy of transferring design risk to Infraco on the date of signature of the Infraco contract.

6.81 While better progress was made with detailed design in the second half of 2007, there continued to be difficulties and delays associated with the design programme and the proposed new procedure for producing self-assured, interdependent and complete packages of design for approval mentioned in paragraph 6.76 above. These are considered below.

Concerns in relation to achieving the design programme

6.82 Throughout 2007 and 2008, concerns were expressed about whether the design programme was realistic and could be met. In its comments dated 30 March 2007 on the draft FBC for the project, Transport Scotland queried whether the intention to complete design by October 2007 was realistic. The assumption of “right first time and on-time delivery” upon which the programme was based also appeared to it to be optimistic, particularly in the context of a unique project in Scotland [TRS00004145, page 0009]. That assumption failed to take into account the iterative nature of design, the complexity of designing and constructing a tram network through any city centre, far less a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the interdependence of various aspects of design.

6.83 A paper presented to the DPD Sub-Committee on 10 May 2007 gave an update on the progress made in resolving outstanding critical design issues [TIE00064787]. A “dashboard” indicated that there were 5,373 design deliverables, relating to 40 design assured packages. An accompanying graph showed that all the design deliverables would be delivered by April 2008. The paper stated:

“There is an important conclusion from this dashboard – the rate of delivery from ‘Now’ must effectively double if the programme is to be met.” [ibid, page 0003.]

6.84 Mr Crawley considered that it was clear that would not be achieved [TRI00000030_C, page 0023, paragraph 38]. Having regard to the history of the slippage of the design programme I consider that it ought to have been apparent to any experienced project manager that such an achievement was practically impossible.

6.85 The minutes of the DPD Sub-Committee on 2 August 2007 noted the concept of “just in time” delivery and the fact there was no margin for error [CEC01530449, page 0007, paragraph 3.2]. Version 17 of the design programme was available and was the first one that it had been possible to prepare since the resolution of virtually all the long-standing critical issues. Design for construction was to be issued between February and June 2008 for different sections. Although the availability of the new version of the programme reflected the ability of PB to recommence work on detailed design and to arrest the delay that had resulted from the lack of instructions from tie on many of the outstanding critical issues, on 9 August 2007 Mr Crawley advised the TPB that PB was unable to recover lost time and the delivery of the programme would be “just in time”. The lack of float in the programme made it vulnerable to the effects of any additional delay [CEC01565001, page 0035].

6.86 By the summer of 2007 it was apparent that it would be impossible to complete the design in accordance with the programme [Mr Bell TRI00000109_C, page 0039; Mr Reynolds TRI00000124_C, pages 0033–0034 and 0085, paragraphs 110 and 250 respectively]. Mr Harries, who was involved in the project between November 2004 and February 2008, never thought that the programme could be met while he was there [TRI00000128, page 0012, answer 16(c)]. Similarly, Mr Glazebrook gave evidence that, in the summer of 2007, he considered that it would be impossible to produce design in accordance with the programme, due to the working and organisational environment. He also said that, throughout his involvement with the project, there was never a time at which he considered that design would be delivered to programme [PHT00000014, pages 161–163].

Procedure for self-assured packages of Design

6.87 As was explained in paragraph 6.76 above, a significant change introduced to improve the rate of delivery of detailed design for approval by CEC was the production of design packages that PB certified as complying with all relevant standards and requirements. This procedure avoided any time required by TSS to review and assure the design on behalf of tie.

6.88 In the event, it did not prove possible to produce complete packages of design that were acceptable to CEC as planning and roads authority. From the email exchange dated 19 and 20 July 2007 between Mr Chandler, of PB, and Mr Conway, of CEC, it appears that there was a tension between what CEC expected from this process and what SDS could deliver within a timescale driven by procurement dates while allowing for subsequent changes to the design once modelling work was completed [CEC01675827]. From that exchange it appears that CEC considered that the self-assurance of designs would not “resolve as many issues as people first thought, particularly with regard to obtaining the technical approvals from CEC”. That was undoubtedly true because approvals and consents from CEC would depend upon final traffic modelling and interdisciplinary checks. Traffic modelling could not be completed before there had been agreement on, and finalisation of, the final design of junctions such as Forth Ports, Picardy Place, St Andrew Square, the Mound, and Haymarket. In fairness, Mr Chandler accepted that the self-assured design packages might be subject to change after the completion of traffic modelling. While he also accepted that this was not ideal, it appears to me that it was a compromise to advance the detailed design that would be available before the signature of the Infraco contract.

6.89 CEC’s concerns about the design packages are reflected in the report to CEC’s Internal Planning Group (“IPG”) on 15 November 2007 that review of the individual disciplines of the detailed design was continuing. The report further noted, however, that

“[t]he packages have yet to be coordinated by the designers therefore the value of these reviews is limited and all packages will require resubmission when complete and fully coordinated by the designers and tie.” [CEC01398241, page 0004.]

6.90 Mr Fraser explained that co-ordination of the packages was very important because the design reviews had limited value if the various design elements could not be considered as a whole [TRI00000096_C, page 0028, answer 32].

6.91 Mr Sharp was initially employed by Transport Scotland with responsibilities for the project but joined tie in October 2007 as its Design and Consents Manager. His responsibilities included addressing the design delay and ensuring that there was in place a plan to remove the obstacles to securing approvals and consents. The strategy had been that “the detailed design would be approved and finished at about the time we were ready to let the infrastructure contract”. The only approvals to be obtained subsequent to the award of the contract would relate to temporary works or changes that Infraco wished to enable it to build the project more economically. This would have enabled about 90 per cent of the Infraco contract price to be fixed. However, when he started as Design and Consents Manager it was apparent that the design would not be completed on time to implement that strategy. The strategy then changed “to get the design as far as possible towards completion to reduce the risk as far as possible” [TRI00000085_C, page 0084, paragraphs 193–194]. I would simply observe at this point that it does not appear that councillors were ever advised prior to the signature of the Infraco contract of that significant change in strategy that would have an obvious impact on the cost of the project.

6.92 Although the SDS contract made PB responsible for obtaining consents and approvals, Mr Sharp gave evidence that there was a realisation within tie that it was not sufficient to rely on PB’s contractual obligation to obtain all the consents that were required, and that he was brought in to tackle the issues in a different way. In short, his responsibility was to make novation happen, but in order to do that he

“had to address the design delay and seek to reduce the design delay and resolve obstacles to the design progressing and to ensure that there was a plan in place to get all of the consents and to help resolve any difficulty – any obstacles to securing these consents” [PHT00000015, page 139].

6.93 The need for a different approach to the consideration of applications for planning consents and technical approvals was also reflected in Mr Chandler’s evidence that for technical approvals CEC required very detailed design that was not achievable in the timescales within which tie wished to award the Infraco contract. He said: “it was almost a mutually exclusive set of requirements or wishes”. He considered that it would have required a “step change” in order for the design programme to be met. Such a step change was required on the part of both CEC, when reviewing and approving design, approvals and consents, and tie, in its engagement with CEC and in showing leadership to resolve issues. What was required was a change from simply listing numerous comments or objections to a more collaborative, or problem-solving, approach whereby CEC would indicate what design would be acceptable [PHT00000020, pages 42–45].

6.94 Mr Sharp also identified poor management within tie that had contributed to the design delay, including a lack of continuity in tie management and an inability to identify a single person within tie who was responsible for managing the SDS contract. While different departments within tie, notably the engineering section, the section concerned with Multi-Utilities Diversion Framework Agreement (“MUDFA”) design, those involved in procurement and those concerned with programme, had a legitimate interest in communicating with PB about design, that should have been confined to a flow of information or exchange of views and should not have included giving instructions to PB. tie’s failure to have a management structure that controlled the issue of instructions by channelling them through one individual meant that PB often received conflicting instructions about the priority to be given to particular aspects of design [PHT00000015, pages 149–151]. Mr Sharp’s evidence in this respect supported the evidence of Mr Reynolds mentioned in paragraph 6.49 above. tie’s failure to control the issue of instructions to PB was a clear defect in its management of the SDS contract and had an adverse impact on the progress of design in accordance with the programme. Mr Sharp addressed this defect in management by requiring that all instructions had to be channelled through him.

6.95 The state of the design at the end of 2007 is best illustrated by an email dated 6 December 2007 from Mr Sharp to Mr Bell and by the report to the IPG on 11 December 2007. The email noted that while the design deliverables due in the current period had generally been delivered, there had been significant slippage on items due in the first and second quarters of 2008 and a significant extension of final delivery date. The reasons given by him for the slippage were the resolution of the Forth Ports and SRU issues, the underestimation of the changes due to the cancellation of EARL, more openness from PB about problems, conservative assumptions in respect of some elements of the programme and attempting to manage an intensive period of design and Infraco due diligence simultaneously [CEC01482817]. The report to the IPG on 11 December 2007 noted that further delays to the design programme were becoming apparent, with all technical reviews programmed to complete after financial close and that CEC required this to be addressed as a matter of urgency [CEC01398245].

6.96 The difficulties and delays with completing detailed design and in obtaining approvals and consents continued until the award of the Infraco contract in the middle of May 2008. The extent of the problem at that time is illustrated by the report to CEC’s IPG on 16 April 2008 [CEC01246992]. At that date, of 63 batched submissions for planning prior approval, only 1 planning permission and 18 prior approvals had been granted: 40 batches had still to be submitted for prior approval (with 26 out of these 40 batches being under informal consideration). No roads technical approvals had been obtained. Roads technical approvals, for different sections, were anticipated to be obtained by various dates between April and October 2008. Prior approvals that had already been granted might require to be revisited if there were substantial changes in design as a result of interdisciplinary co-ordination, technical approvals or value engineering.

6.97 The significance of these delays was recognised in the following comment:

“There is potential for the approvals to cause a delay to the construction programme” (emphasis in original). [ibid, page 0004.]

6.98 Later in the report it was recognised that CEC would be exposed to claims exceeding £2 million if construction work at Russell Road bridge, Haymarket tram stop and the depot at Gogar, three locations on the critical path for the tram delivery, were delayed pending receipt of the appropriate planning prior approvals. The proposed mitigation was for CEC to allow the work to commence without the necessary approval but that would affect the rights of people wishing to object to the prior approvals during the consultation period and could expose CEC to a legal challenge of the decision to allow the work to proceed. This proposed approach reflects emails and discussions involving members of the “B team” at CEC and their concerns about delays in obtaining prior approvals, and tie’s proposed unauthorised commencement of piling discussed in Chapter 14 (CEC: January–May 2008) [paragraphs 14.67–14.71]. Although the Tram Acts authorised the construction of structures along the route of the network, including Russell Road bridge, such authorisation was equivalent to outline planning permission and tie had to obtain detailed planning permission for the structure that it intended to build. Prior to the grant of detailed planning permission tie would require to comply with planning legislation and procedures including giving interested members of the public the right to object to the design of the proposed structure. The final form of the structure would affect the nature and design of the piling required.